Día de los Muertos is a time for people to mourn the loss of family members and friends, and to ensure they’re never forgotten, says Michelle Téllez.

Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a holiday with roots in Mexico that’s now celebrated over two days, November 1 and 2, all over the world.

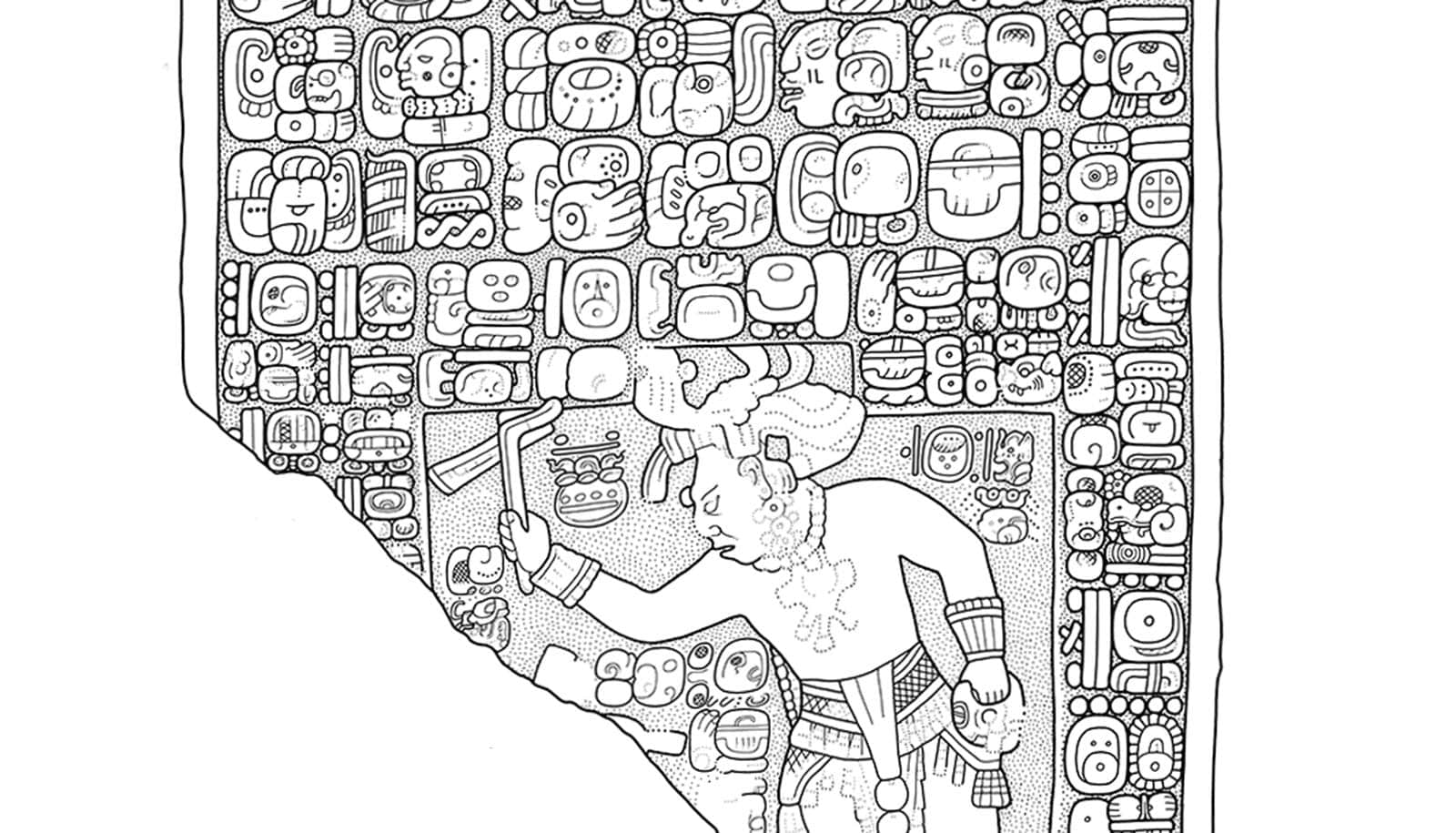

The holiday’s unique symbols are ubiquitous in some locations come October: Calaveras, or skulls—often in the form of edible, decorative sugar skulls—and papel picado, pieces of colorful paper with intricately cut-out designs.

Téllez, an associate professor in the Mexican American studies department in the University of Arizona’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, researches transnational community formations, Chicana mothering, gendered migration, and more.

Here, Téllez, who is also the department’s director of graduate studies, discusses the history, traditions, and imagery of Día de los Muertos, how the holiday has changed over millennia, and how those interested can participate:

What is Día de los Muertos, and how and when did its traditions and rituals originate?

Día de los Muertos, the way we celebrate it here in the United States, emerged in Mexico, and it has had many evolutions over the course of 3,000 years in terms of what we understand it to be today.

The holiday on November 1 and 2 is a moment in time to honor your ancestors and those in your family and community who have gone into the spirit world. It emerged from an Aztec ritual known as Miccaihuitl, and Miccaihuitl was an honoring of the dead, but it was also the time for harvesting. It was this moment for recognizing a seasonal change from light to dark as we’re transitioning into the fall.

Then you have the Spanish arrival to the Americas, bringing with them Christianity and Catholicism. They had their own celebrations that they tried to syncretize with traditional Indigenous ceremonies. So, Día de los Muertos today is the bringing together of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day with this traditional honoring of our ancestors.

What traditions do Día de los Muertos observers practice?

Día de los Muertos is an opportunity for families to create altars for their loved ones. Many argue that if you remember them, they never cease to exist. The altars can be made in so many ways, but some of the core elements would be a photo of the deceased, their favorite foods, flowers.

You can also include a representation of the four elements, so a candle or copal—incense—for fire, a cup of water, and then the wind and earth might be represented by papel picado. Some people, depending on where you are in the world, go to the cemetery to build their altars. But, because of migration, sometimes we’re not in the places where our loved ones are buried, so you make the altars in your home.

But many people do it differently: Some people have full-on parties, and some people have a velación, or observance, which means you just honor your loved ones not necessarily with prayer, but in a solemn space.

In those two days, you spend time with those memories. And you don’t leave the altar up for days, because it’s sacred. You take the time to close the ceremony or that moment of engagement with your memories and those ancestors who are no longer with us.

Día de los Muertos is often conflated with Halloween, despite having no connection to that holiday. Why do you think that happens, and why can it be problematic to associate the two?

I think it’s just because of the time of year—they’re both in the fall. I started seeing people dress up and they would say, “I’m Día de los Muertos for Halloween,” and it would be so clear to me that they had no idea what they were talking about. It would be different to dress up as a catrin or a catrina, which is an embodiment of a calaca, or a skeleton. But because they start conflating the two, you see people not only dressing up as “Día de los Muertos” for Halloween, but you also see Halloween parties with altars. They should be different things.

The calaveras, or skulls, and calacas, or skeletons, have become icons of Día de los Muertos. How did that originate, and what do the symbols mean?

I couldn’t tell you exactly when people started using these, but I’m assuming it has to do with the early 20th-century political artist José Posada, who started making these calacas that we’re familiar with now, drawing from his sort of play on life and death and war and poverty and culture. Drawing on that tradition, people started using face-painting as an example of life and death, so you’ll see that.

At the most basic level, the skulls represent a departed spirit. While we’re drawing from an ancestral tradition, it’s not like the sugar skulls were there when these traditions, practices and rituals started. But culture and traditions evolve. This imagery is one of the most obvious ways to convey this notion of life and death, our mortality as humans, and our constant dance with life and death.

How can people learn more about the traditions or even participate?

There are some really great books out there. I would recommend Juanita Garciagodoy’s Digging the Days of the Dead: A Reading of Mexico’s Dias de Muertos (University Press of Colorado, 1998) for adults. And for kids, The Remembering Day/El día de los muertos (Piñata Books, 2015), by Pat Mora.

It’s not wrong to want to honor your loved ones, and if you do that with that intention, I think that’s a beautiful thing. I would find ways to participate in a community celebration where they’re actually honoring that tradition. In Tucson, we have the All Souls Procession, but from what I understand, the organizers see that as something very different; it’s related, but it’s not a Día de los Muertos event. But that is one way for people to really connect with others. Mourning can be a very isolating thing, and some people want to be in community to connect with others going through a similar experience.

Or, you can make your own altar and it can just be very simple—a candle and a photo. I think that’s a beautiful way to keep those people we love present and to teach our families about them. I have a daughter, and she might not have known my father but because I bring him into my home every year, she feels connected to him.

As someone who has a personal connection to these traditions, who will you be thinking about during Día de los Muertos?

This is personally one of my favorite times of the year. My family is from a little town called Tomatlán, Jalisco, and the tradition is to go to the cemetery to honor our relatives. We have an area of the cemetery where at least three generations of our family are buried. However, when my mom migrated, she didn’t bring that tradition here because we were so far. So, I didn’t necessarily grow up with it.

My father passed away suddenly when I was 20, and it was just such a life-changing experience that I needed to find a way to remain connected to him. Around that time is when I also started learning more about this tradition and learning more about how to create the altar and what it signifies. For me, it was a tradition that I started to do that then expanded to my immediate family. And now it’s something that my daughter can say she was raised with because I’ve been making altars with her for her entire life.

This year, I’ll be thinking about all of the families who have lost loved ones to COVID, and I’ll be thinking about my own personal losses this year. I always honor my parents on my altar; they’re the center of the altar. My mom loved Almond Roca, so we always include it. And my daughter sometimes will tease me by saying, “When I have to put you on an altar, Mami, I’m going to put Double Stuf Oreos!”

It’s a way for us to sort of normalize this cycle of life that we live. It’s not easy—it’s one of the worst things to lose someone you love. But I know that long after I’m not present, I will have a place in this ceremony with my daughter for the rest of her life.

Source: University of Arizona