A parasitic amoeba that causes a potentially deadly infection kills human cells by nibbling them to death—much like a piranha attacks its prey.

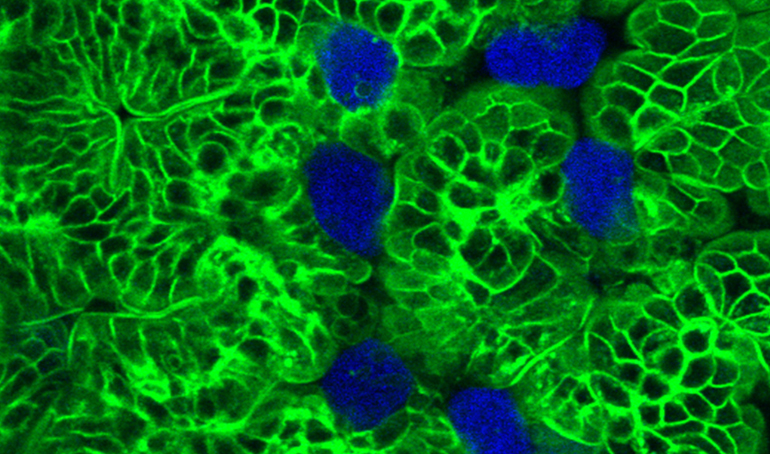

Until now, researchers had assumed that the amoeba, Entamoeba histolytica, killed and then engulfed and consumed human cells. But new research upends that idea, suggesting instead that it takes small bites of the cell until the cell dies—and then loses all interest in eating the corpse.

“This is the first demonstration that nibbling can serve as a way to kill other cells,” says Katherine S. Ralston, a researcher at the University of Virginia.

“The findings suggest that amoebae might invade and destroy host intestinal tissue by nibbling alive the cells that line the gut. Intriguingly, there are hints that organisms can also nibble. Perhaps this process is more common than we realize, and it is taken to the extreme in the case of the amoebae, which use nibbling to kill.”

[related]

It’s important to understand Entamoeba histolytica, because it causes a potentially fatal diarrhea common in the developing world. Approximately a third of all infants are infected within their first year of life in the Bangladeshi slum where the researchers work.

The amoebae colonize the colon and begin their nasty work, which can produce diarrhea, inflammation of the colon, bowel diseases—or no symptoms at all.

Unstable cell membranes

Rather than poisoning human cells, as has been previously thought, the amoebae appear to nip at the cellular membrane, as a goldfish might nip at another goldfish. Eventually, the amoeba consumes enough of the membrane—the cell’s casing—that the membrane becomes unstable and the cell dies. The amoeba then detaches itself from its dinner and moves on to another, still-living meal.

“It has been 111 years exactly since this parasite was named ‘histolytica’ for its ability to lyse tissues, says William A. Petri Jr., chief of the University of Virginia’s infectious diseases and international health division.

“Finally, the way it kills has been discovered. This provides an avenue to explore how best to prevent and treat this parasite that infects up to one of every three children by their first birthday in Bangladesh.”

The researchers hope the new findings will help lead to new treatments for amoebiasis, the disease the amoebae cause.

The findings are published as a letter in Nature. Other researchers at University of Virginia and at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, are coauthors.

Source: University of Virginia