New research finds a clever use for the dandelion: each of its tiny seeds can work as a perfect pipette in the lab.

“We found you can actually use dandelion seeds to perform precise droplet handling. There aren’t many tools that exist for this,” says Guy Genin, professor of mechanical engineering at the Washington University in St. Louis School of Engineering & Applied Science.

The team examined the wettability of dandelion seeds, or how liquids saturate them. While most materials can be wetted only by water (hydrophilic) or oil (oleophilic), the researchers found the pappus of a dandelion—the fluffy, white structure surrounding the seed—is omniphilic, able to be saturated by both materials. That rare trait makes it an extremely useful lab tool, especially when it comes to moving tiny amounts of either liquid from one setting to another.

(Credit: ILRI/Flickr)

“These dandelion pappi are chemically and structurally composed so that they will collapse in a special way if you dip them in either oil or water,” says Feng Xu, Genin’s collaborator and director of the Bioinspired Engineering and Biomechanics Center at Xi’an Jiaotong University. “Using the pappi, you can lift up a drop of water and deposit that drop of water into an oil bath. And you can go back into the oil, use the pappi to retrieve the drop of water, and move it elsewhere.”

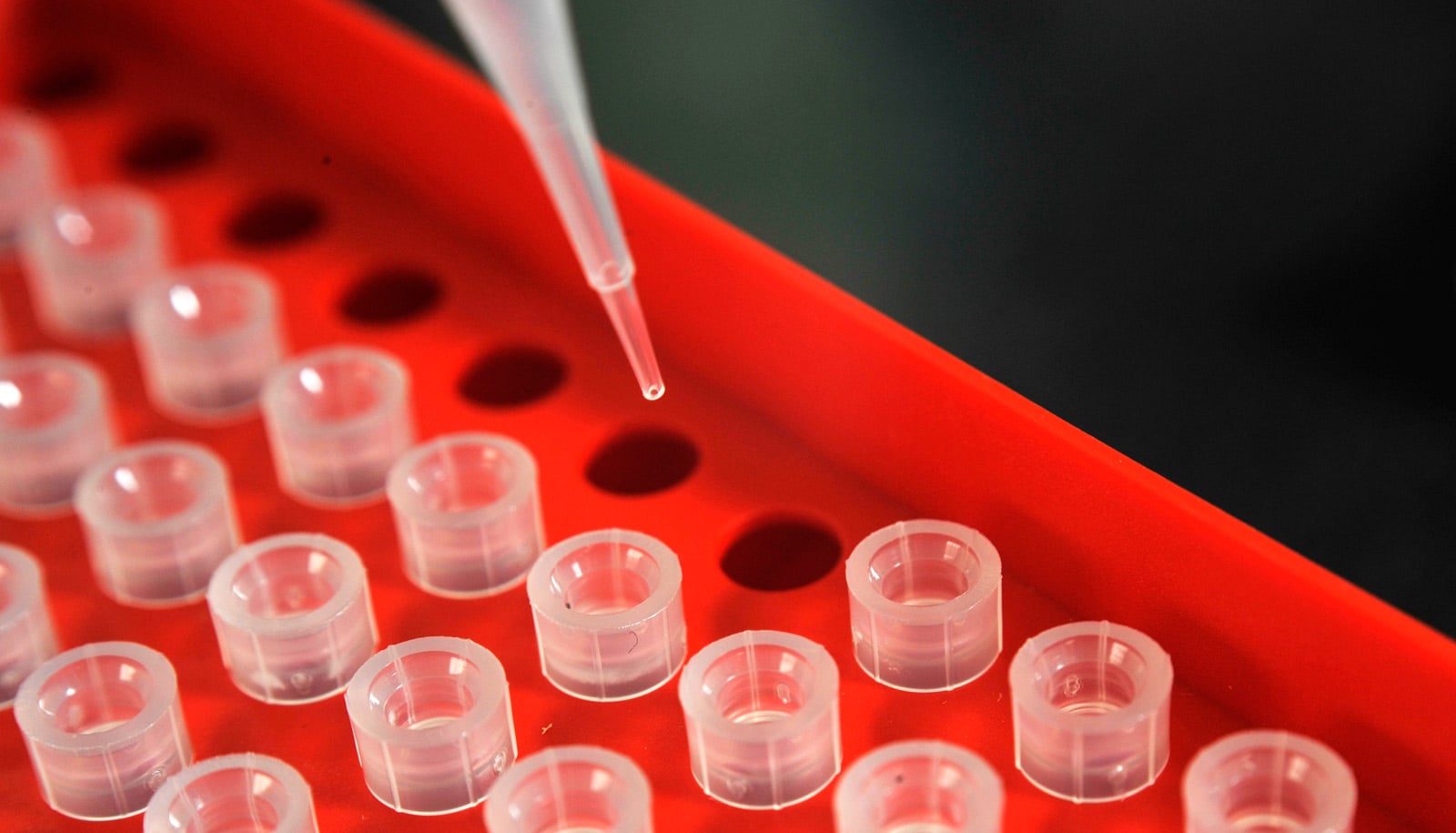

Genin says using dandelions in the lab allows for precise handling of minute amounts of liquid, something especially important for the tiniest of experiments.

“Because it has this special omniphilic property, the seed provides us a new way of handling nanoliter-sized droplets in the lab. They are a beautiful controlled environment; they basically seal off the work around them so we can run a very controlled chemical reaction with them.

“The dandelion comes self-assembled, naturally grown, and its seeds are able to reliably and repeatedly pick up these tiny volumes of fluid that we need to transport in a lab setting.”

Lego robot squirts liquid in DIY lab for kids

The seeds can be used either individually or in large assays to collect greater amounts of liquid. Genin says the next step is to replicate the pesky dandelion’s omniphilic properties in synthetic materials.

“We hope to be able to develop bio-inspired omniphilic surfaces to create additional options for handling liquid for lab experiments,” Genin says.

Advanced Functional Materials recently published this research, which had financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.