A new study puts forward a new concept: a “general distractibility” trait, called “d” factor, that people prone to external and internal distractions share.

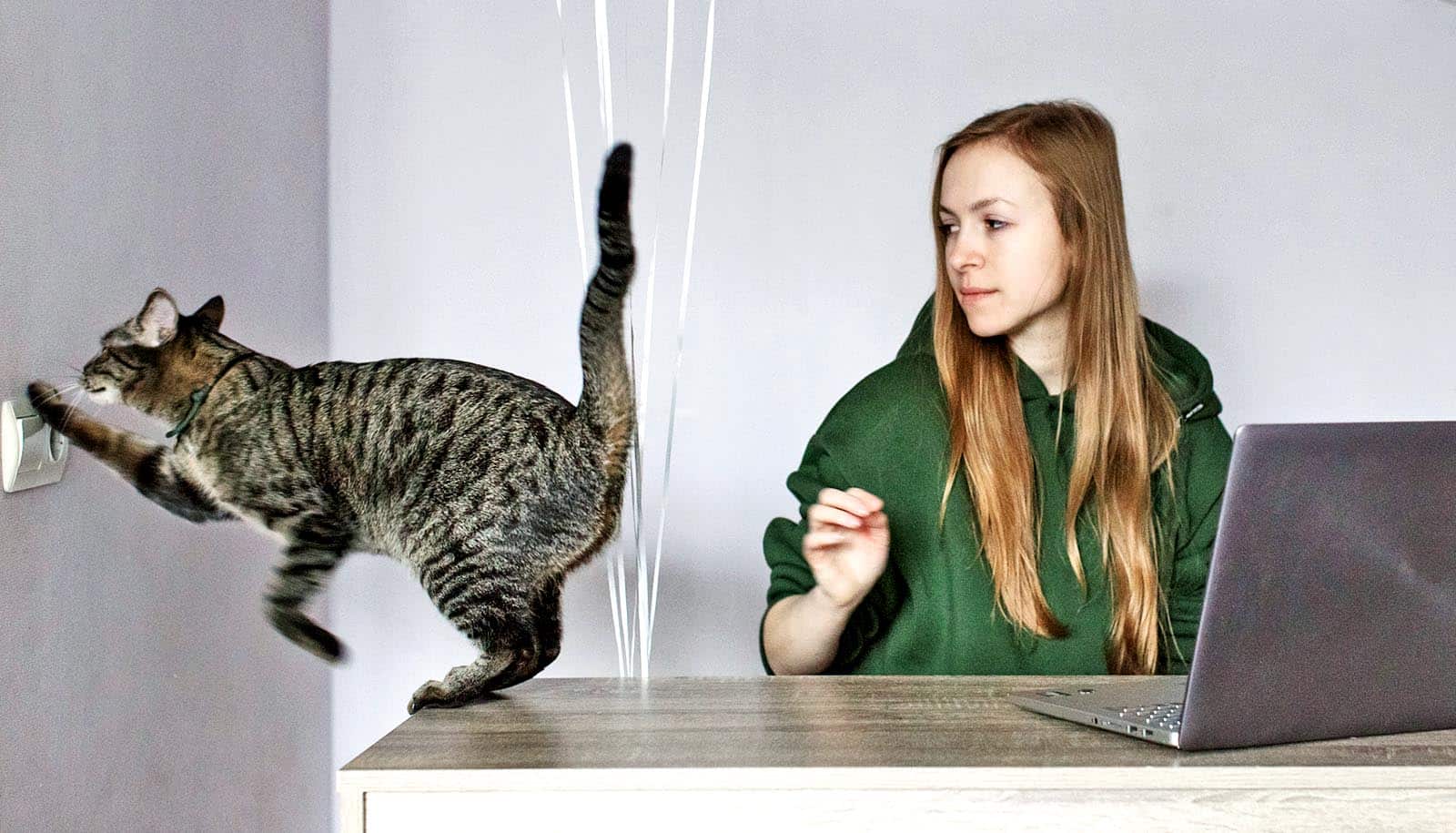

As you read this, you might be distracted by external stimulations like people talking near you or a smartphone notification. Or, perhaps it’s internal factors such as overthinking about an unpleasant memory or daydreaming.

The “d” factor had a strong correlation with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, suggesting heightened distractibility as a core ADHD deficit.

High “d” scores also relate to more “hyperfocus,” a prolonged state of intense focus. This suggests both hyperfocus and distractibility may involve challenges in attention regulation, says Han Zhang, a University of Michigan psychology doctoral student and the study’s lead author.

“Understanding individual differences in distractibility is important not only for predicting for whom attention is likely to fail, but also for understanding the cognitive underpinnings of psychopathology,” he says.

Previous studies have shown that people who report being distracted more easily are at a higher risk of poor performance in school and work settings. They are also sometimes prone to serious accidents.

Zhang and colleagues gathered data on 1,200 participants, ages 18 to 35, who completed more than a dozen questionnaires about being distracted in their daily lives. The questionnaires also evaluated symptoms of ADHD and hyperfocus.

The results indicated that the “d” factor predicted a person’s tendency to engage in external distraction, unwanted intrusive thoughts, and mind-wandering. It was also related to ADHD symptoms and functional impairments.

In addition, the findings indicated that individuals who were more distractible reported frequent hyperfocus episodes. Zhang says this counterintuitive relationship implies that focused and distracted attention might share some underlying features.

One possible interpretation is that individuals often hyperfocus on the same subjects that distract them from more critical tasks. For example, someone might hyperfocus on watching TV, which serves as a distraction from their work assignments, he says.

The study appears in PLOS ONE. Coauthors are from the University of Colorado and the University of Michigan.

Source: University of Michigan