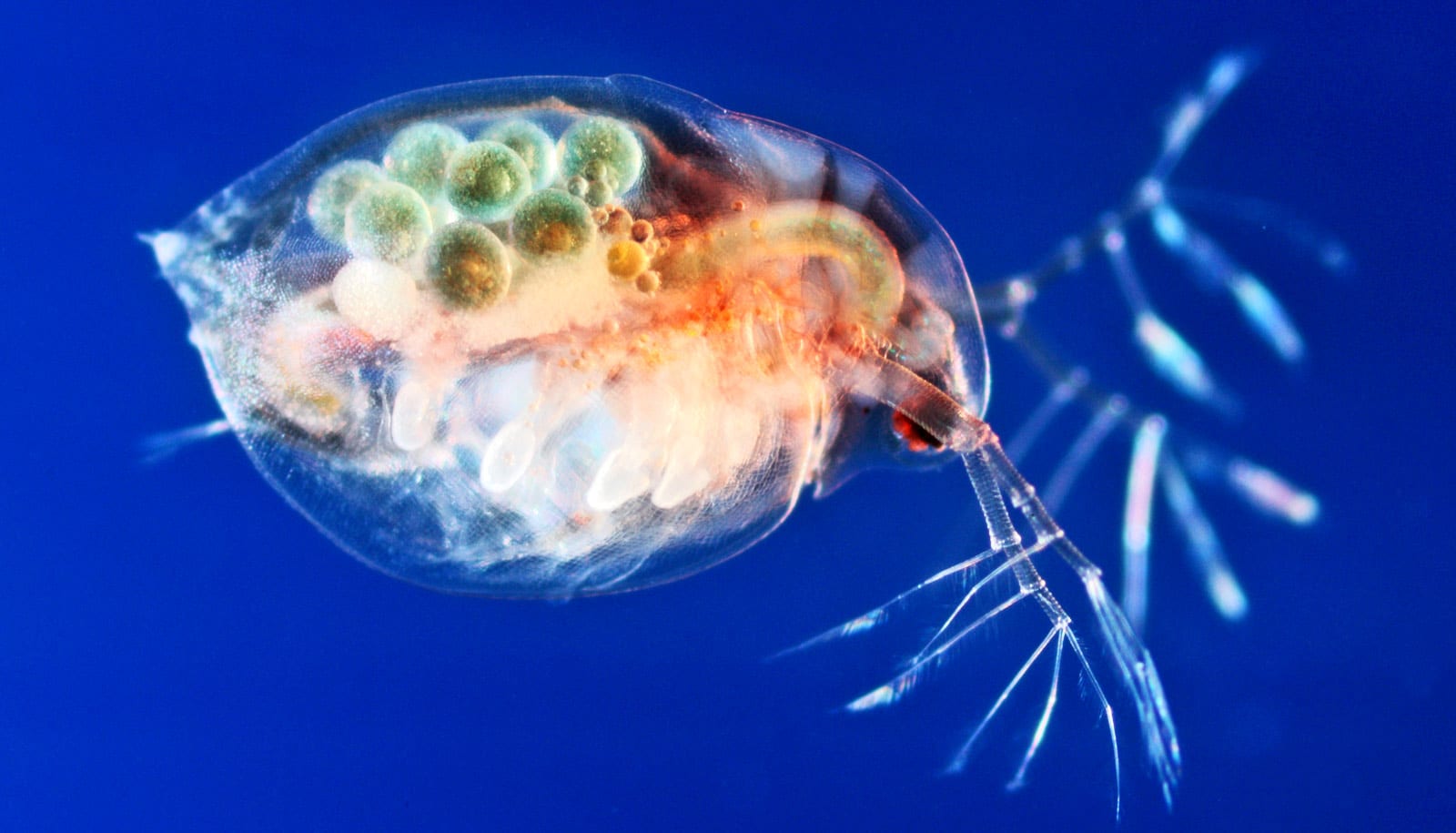

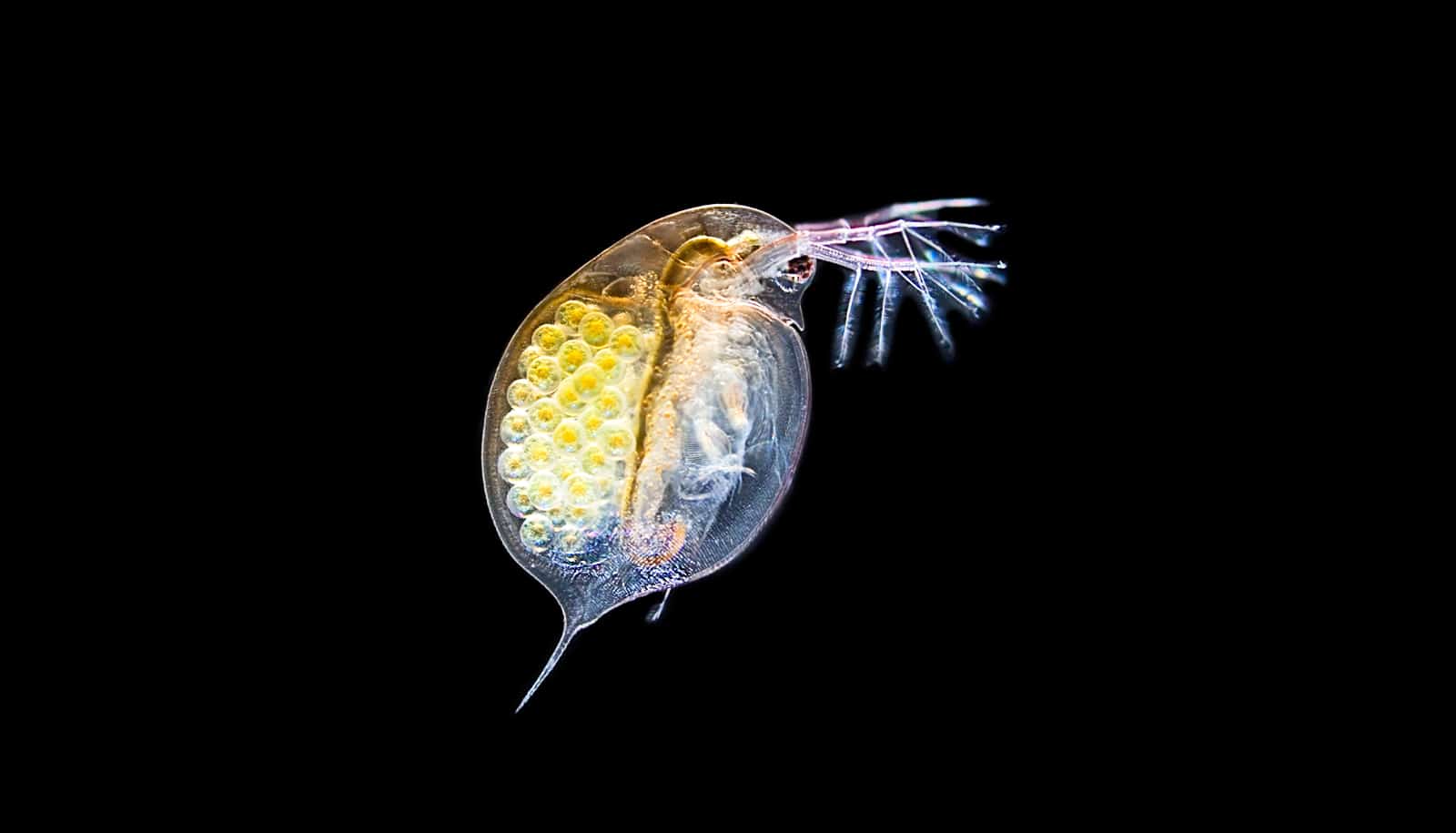

Cyanobacteria produce liver toxins harmful to people and their pets, but they shield tiny shrimp-like crustaceans from fungal parasites.

New research shows the toxins protect sand-grain-sized lake animals called Daphnia that eat them, the same way toxins in milkweed plants protect monarch butterflies from parasites.

Commonly known as water fleas, Daphnia play a key role in freshwater food webs and are a vital food source for many fish.

“This paper shows that Daphnia living in Michigan lakes can gain protection from fungal parasites through the toxins that are present in bloom-forming cyanobacteria,” says ecologist Mark Hunter, who studies monarchs at the University of Michigan’s Biological Station.

“This is an amazing aquatic parallel of the monarch butterflies, which gain protection from their parasites from the toxins in milkweed. It suggests that animal medication may be even more common than we thought, extending into the aquatic realm.”

Animal pharmacies

Scientists have known for decades that animals such as chimpanzees seek out medicinal herbs to treat their diseases. In recent years, the list of animal pharmacists has grown much longer, and it now appears that the practice of animal “self-medication” is a lot more widespread than scientists had previously known.

But most studies of animal self-medication focus on terrestrial ecosystems. Scientists know little about how an animal’s diet offers medications in aquatic systems.

To be clear, the current study doesn’t show that Daphnia are self-medicating in the wild. To demonstrate self-medication, researchers would have to show that Daphnia feed preferentially on toxin-producing cyanobacteria and algae to reduce their disease risk. The researchers will look for evidence of this type of selective foraging in the next phase of the study.

But the findings do provide strong evidence for the protective properties of plant toxins Daphnia consume.

“Fungal pathogens have devastating impacts on crops, wildlife, and even people,” says ecologist Meghan Duffy. “To me, the idea that compounds for fighting those might be just below the surface of our local lakes is really exciting.”

Daphnia diets

For the study, first author Kristel Sánchez raised Daphnia dentifera, a common herbivore in North American lakes, in the lab and fed individuals one of eight species of green algae or cyanobacteria (formerly known as blue-green algae).

In the wild, Daphnia feed on algae and bacteria floating in the water column; a group of tiny aquatic animals called zooplankton grazers.

Researchers used five species of green algae and three species of cyanobacteria. They differed in their nutritional value and toxin production. Green algae tend to be more nutritious for Daphnia than toxin-producing cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacteria used in the study included one species of Microcystis, a group of common colony-forming cyanobacteria largely to blame for Lake Erie’s annual summer blooms. Some Microcystis species produce liver toxins called microcystins.

“The fact that nearly half of the diet treatments showed some sort of medicinal effect was really surprising…”

In her experiment, Sánchez added pure microcystin to some of the Microcystis cultures to approximate levels of the toxin commonly observed during cyanobacteria blooms.

Researchers then exposed the lab-reared Daphnia to one common fungal parasite and one common bacterial parasite. In the wild, Daphnia become infected by consuming parasite spores in the water.

The researchers discovered that diet had striking effects on the infection prevalence of the fungal parasite, but not the bacterial parasite.

Two of the cyanobacteria diets—including the diet treatment where scientists added pure microcystin to beakers containing Microcystis cultures—completely prevented fungal infections. The diet of Microcystis alone, without additional microcystin, resulted in very low levels of fungal infection.

Also, when Daphnia fed on the green alga Chlorella, it completely prevented fungal infections. In all, four of the nine dietary treatments showed strong evidence of anti-fungal activity.

“I thought I would probably get one diet out of the nine that showed some medicinal effect,” Sánchez says. “The fact that nearly half of the diet treatments showed some sort of medicinal effect was really surprising and suggests that we are not paying enough attention to the mechanism of self-medication in aquatic ecosystems.”

In contrast, none of the diet treatments prevented infection with the bacterial parasite. Also, uninfected Daphnia that consumed a diet of green algae produced two- to three-fold more offspring than those that ate cyanobacteria. This confirms the higher nutritional quality of the green algal diets. And, in general, parasite infection reduced growth.

Disease dynamics

In the next phase of the study, the researchers will look for evidence of self-medication and will further examine the anti-microbial properties of the three toxins that showed fungal-fighting activity in the initial study: microcystin-LR, anatoxin-a, and chlorellin.

“A lot of natural products research is done by screening tons of plant or algal material and using different bioassays and hoping you get lucky and find a new compound or something that is active,” Sánchez says. “But why not look at what is happening already in nature? I think this is what really appealed to me and why I chose to work on this project.”

The work has broad ecological implications, in part because a warming global climate is expected to increase the frequency of cyanobacteria blooms in some regions, the researchers say. That change could alter disease dynamics among Daphnia, which in turn “could have important consequences for lake food webs, since Daphnia are key grazers and disease outbreaks within Daphnia populations can influence ecosystem-level processes.”

The paper appears in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The University of Michigan ecology and evolutionary biology department, the Frontiers Master’s Program, and the National Science Foundation supported the work.

Source: University of Michigan