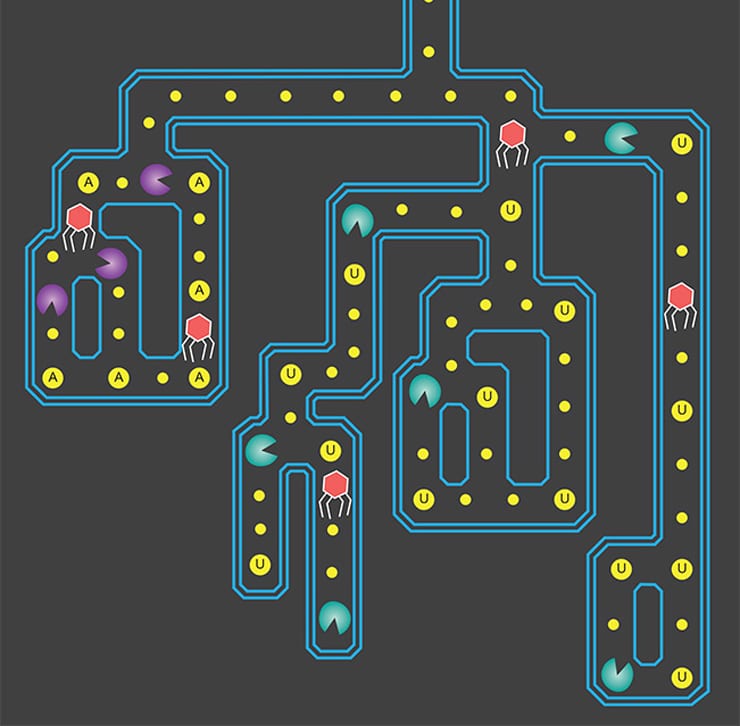

Once activated, 10 newly described CRISPR enzymes behave like Pac-Man to run amok and destroy RNA. The findings could be useful for detecting infectious viruses.

The new enzymes are variants of a CRISPR protein, Cas13a. In September, scientists reported in the journal Nature that Cas13a could be used to detect specific sequences of RNA, such as those from a virus. They showed that once it binds to its target RNA, it begins to indiscriminately cut up all RNA linked to a reporter molecule, making it fluoresce to allow signal detection.

Researchers subsequently paired CRISPR-Cas13a with RNA amplification, and showed that the system—which they dubbed Sherlock—could see viral RNA at extremely low concentrations to detect the presence of dengue and Zika, for example.

Such a system could be used to detect any type of RNA, including RNA distinctive of cancer cells, researchers say.

While the original Cas13a enzyme cuts RNA at one specific nucleic acid, uracil, three of the new Cas13a variants cut RNA at adenine. This difference allows simultaneous detection of two different RNA molecules, such as from two different viruses.

“We have taken our foundational research a step further in finding other homologs of the Cas13a family that have different nucleotide preferences, enabling concurrent detection of different reporters with, say, a red and a green fluorescent signal, allowing a multiplexed enzymatic detection system,” says first author Alexandra East-Seletsky, a graduate student in the laboratory of Jennifer Doudna at the University of California, Berkeley. Doudna is one of the inventors of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool.

The new findings appear in Molecular Cell.

Killing spree

The CRISPR-Cas13a family, formerly referred to as CRISPR-C2c2, is related to CRISPR-Cas9, which is already revolutionizing biomedical research and treatment because of the ease of targeting it to unique DNA sequences to cut or edit.

While the Cas9 protein cuts double-stranded DNA at specific sequences, the Cas13a protein—a nucleic acid-cutting enzyme referred to as a nuclease—latches onto specific RNA sequences, and not only cuts that specific RNA, but runs amok to cut and destroy all RNA present.

Using CRISPR against cancer shows success in mice

“Think of binding between Cas13a and its RNA target as an on-off switch—target binding turns on the enzyme to go be a Pac-Man in the cell, chewing up all RNA nearby,” East-Seletsky says. This RNA killing spree can kill the cell.

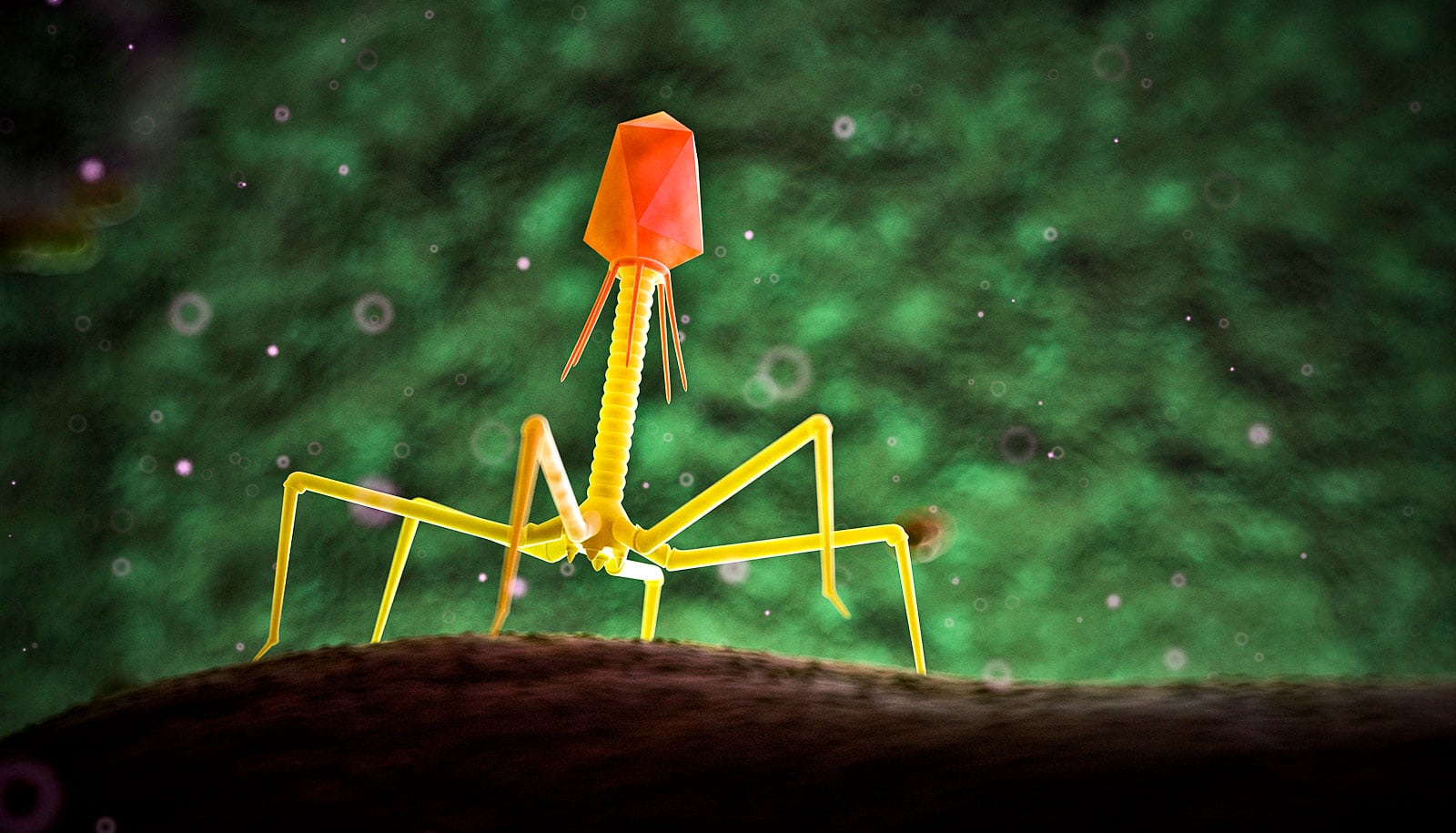

In the Nature paper, researchers argued that the Pac-Man activity of CRISPR-Cas13a is its main role in bacteria, aimed at killing infectious viruses or phages. As part of the immune system of some bacteria, it allows infected cells to commit suicide to save their sister microbes from infection. Similar non-CRISPR suicide systems exist in other bacteria.

The researchers subsequently searched databases of bacterial genomes and found 10 other Cas13a-like proteins, which they synthesized and studied to assess their ability to find and cut RNA. Of those, seven resembled the original Cas13a, while three differed in where they cut RNA. RNA, which serves many functions inside the cell, including as messenger RNA—working copies of DNA—consists of four different nucleotides: adenine, cytosine, guanine, and uracil.

A big, diverse family

“Building on our original work, we now show that it is possible to multiplex these enzymes together, extending the scope of the technology,” East-Seletsky says. “There is so much diversity within the CRISPR-Cas13a family that can be utilized for many applications, including RNA detection.”

Gene editing in monkeys, not mice, could improve research

Doudna, a professor of molecular biology and of chemistry and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, says detection of infectious RNA may or may not require amplification, which is a complicated step.

“Our intention is to develop the Cas13a family of enzymes for point-of-care diagnostics that are robust and simple to deploy.”

Former UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Mitchell O’Connell, now an assistant professor at the University of Rochester, and UC Berkeley postdocs David Burstein and Gavin Knott are coauthors of the study.

The work was supported in part by a Frontiers Science award from the Paul Allen Institute and by the National Science Foundation.

Source: UC Berkeley