In dinosaurs’ heyday in the late Cretaceous Period roughly 78 million years ago, Earth’s climate was both warmer and more varied than what we have known before, researchers report.

Dinosaurs of the northern mid-latitudes (45 degrees north of the equator) experienced average summer temperatures of 27 degrees Celsius (about 80 degrees Fahrenheit). Winters were roughly 15 degrees C (59 degrees F).

This is both warmer—about two degrees—and more volatile than late Cretaceous calculations proclaimed.

One of the reasons today’s climate models fail is that they haven’t taken into account changing seasonal temperatures, says Nicolas Thibault, an associate professor at the University of Copenhagen’s geosciences and nature management department and one of the researchers behind the study in Communications Earth and Environment.

“Until now, oxygen isotopes in Cretaceous fossils were analyzed to determine the temperature during the period. This measurement was the starting point for the whole year, without consideration for large fluctuations in seasonal temperatures between summer and winter. As such, a snapshot was allowed to determine an entire period of time,” he says.

Furthermore, the researchers do away with the idea that warm average temperatures moderate fluctuations in seasonal temperatures, as is the case in the tropics today.

“Our results demonstrate that dinosaurs in the northern hemisphere lived in extreme heat, when average summer temperatures hovered around 27 degrees [Celsius]. As such, one can well imagine that there were summer days when temperatures crept above 40 degrees. However, winters were mild and wet,” Thibault says.

Lots of CO2 during Cretaceous Period

Other than the fact that Cretaceous Period reconstructions never took seasonal temperature fluctuations into account, they have another fundamental problem as well.

They assume that the chemical composition of the world’s oceans has been constant throughout the ice-free Cretaceous Period. But this, Thibault says, is not the case.

“Recent research shows that the level of oxygen isotopes in seawater changes seasonally and is thus far from stable. We used this knowledge in our analysis of Cretaceous Period temperatures, where we find dry summers and wet winters,” he elaborates.

In fact, the researchers’ study demonstrates that there was four times as much CO2 in the atmosphere during the late Cretaceous Period compared to the 1900s industrial era—with CO2 levels even higher than today.

Clues in mollusk shells

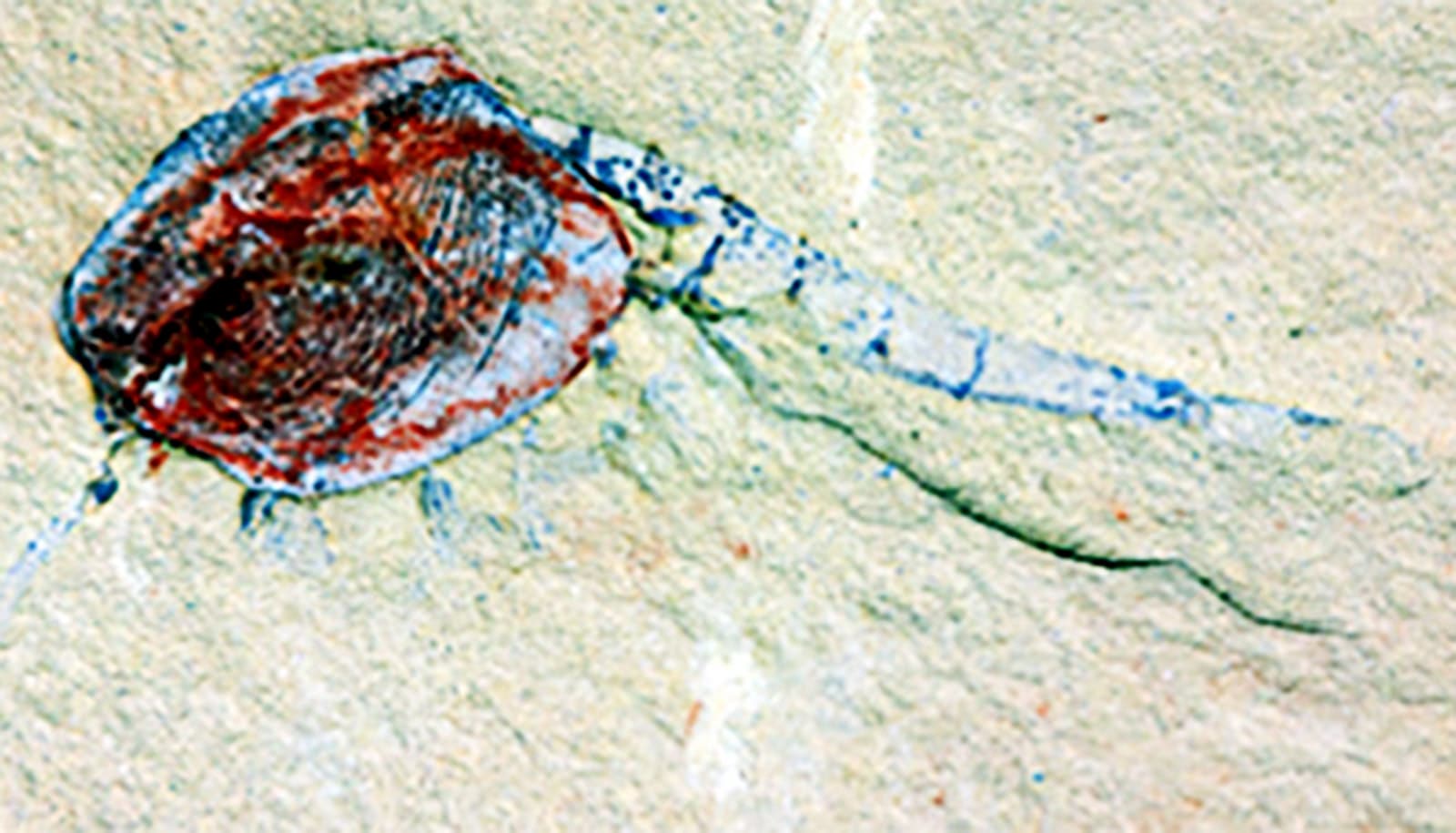

The researchers used fossils of oysters and other mollusk species from the Kristiansand Basin in southern Sweden to analyze temperatures during the Cretaceous Period—just like previous models.

However, they used a new method that makes it possible to measure the temperature directly from carbonate in the mollusk shells. The researchers are not looking at individual oxygen isotopes, but at clusters of them.

“This allows us to achieve a far more accurate result. We are investigating the chemical content of seashells that formed over a course of several years. We compare this with our knowledge about the marine environment and the average temperatures of the late Cretaceous Period.

“In doing so, we can see that it was actually warmer than previously thought and that temperatures fluctuated a lot,” Thibault says.

Past climate key to future climate

The researchers’ results point to significant errors in previous climate calculations for the Cretaceous Period that need to be corrected, Thibault says.

“With our research, we are able to show how to improve climate models by including data on fluctuating seasonal temperatures and changed chemical compositions in the marine environment.”

Our understanding of the climate in the past is the key to understanding what the world will look like in the future. Thus, the results of this new study will most likely change our predictions about temperatures both internationally and in Denmark.

“Our summers are likely to be even hotter and drier than predicted thus far,” says Thibault, who stresses that he cannot assess the exact temperature change.

Niels de Winter from Vrije Universiteit in Belgium is the paper’s lead author.

Source: University of Copenhagen