A new COVID test that relies on gargling with saltwater instead of using a nasal swab shows encouraging initial results, researchers say.

Michael Worobey, head of the ecology and evolutionary biology department at the University of Arizona, specializes in the evolution of viruses. He began using the mouth rinse test in limited campus populations after reading a paper from researchers in British Columbia published on medRxiv, a preprint server for health sciences research.

While papers published on preprint servers have not yet received peer review and therefore should be treated as preliminary, Worobey deemed the report convincing enough to give the mouth rinse approach a shot.

He has since used the test to collect samples from University of Arizona students in isolation dormitories who have already had a positive COVID test, as well as from students, staff, and faculty willing to enroll in his study immediately after providing samples for clinical testing through Campus Health.

The sampling effort aims to collect as many virus genomes as possible as part of an ongoing study that seeks to discover how SARS-CoV-2 evolves over time and how it spreads through the human population. Initial results have been encouraging, says Worobey, who also is associate director of the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute.

“It’s vastly more tolerable than the nasopharyngeal swab, and people can do it all by themselves and even keep their mask on almost the whole time,” says Worobey, who doesn’t know of any other US universities using the mouth rinse test.

Demonstrating the COVID test himself, Worobey cracks open a crayon-sized, pink plastic vial containing a liquid. “Off comes the top, you pull your mask down, and you just squirt a bit of sterile saltwater into your mouth.”

Worobey swishes the liquid around in his mouth for five seconds, then tilts his head back for 10 seconds of gargling. After a total of three cycles of swishing and gargling, Worobey spits the liquid into the specimen cup and screws the lid back on.

“And that’s it,” he says, “you’re done.”

A more sensitive COVID test

Based on his results, the mouth rinse test is more sensitive than a nasopharyngeal swab test, Worobey says. It also appears to be considerably more sensitive than a test based solely on saliva samples, where test subjects simply spit into a cup.

The reason for the increased sensitivity, Worobey says, could have to do with the fact that the test pulls virus particles from the throat during the saltwater gargle phase in addition to the saliva collected during the mouth rinse procedure.

The saltwater gargle approach is also ideal for the extremely dry climate typical of fall in southern Arizona, which makes it difficult for some people to stay properly hydrated and produce the necessary amount of saliva needed for a spit test.

“Our system allows the participants to painlessly collect virus from the back of their throat in a way that, so far, seems superior in terms of its ability to detect the virus,” Worobey says.

When Worobey tested the first person in the study, using both the nasal swab and the saline gargle samples, the virus was detectable only in the gargle sample. Out of more than 100 people screened, he now has paired nasopharyngeal and saline gargle samples from 30 coronavirus-positive patients. In this head-to-head comparison, the oral rinse samples detected the virus in about 20% more patients than the nasopharyngeal ones.

“This shows that the salt rinse and gargle test can be more sensitive and catch an infection you’d miss with the nasopharyngeal test,” he says. “It also suggests that it’s doing a good job of detecting virus in people who have or recently had the virus.”

Cracking the coronavirus genome

Soon after the pandemic began, Worobey embarked on research that aimed to collect as many complete genome sequences of the coronavirus as possible, in a collaboration with David Harris, director of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Biorepository.

Worobey also is one of three principal investigators for the Arizona COVID-19 Genomics Union, a joint effort between University of Arizona, Northern Arizona University, and the Translational Research Genomics Institute that was set up to perform high-throughput sequencing of samples from COVID-19 patients to analyze the virus’s genomic sequences.

Accurately deciphering the viral genome, which consists of about 30,000 nucleotides—essentially the letters spelling out the genetic blueprint of all organisms—allows researchers and health officials to track different strains, track where each sample originated and where it may have been transmitted, and possibly reveal details that could provide critical information for diagnostics, antiviral drug targets, vaccine development, and prevention of future pandemics.

“I think the saltwater gargle will work better than nasopharyngeal swabs,” Worobey says, “because for a research study, and eventually clinical testing, you need to get people to be OK with participating, and any kind of unpleasantness you throw at them means a lower percentage of people will participate.”

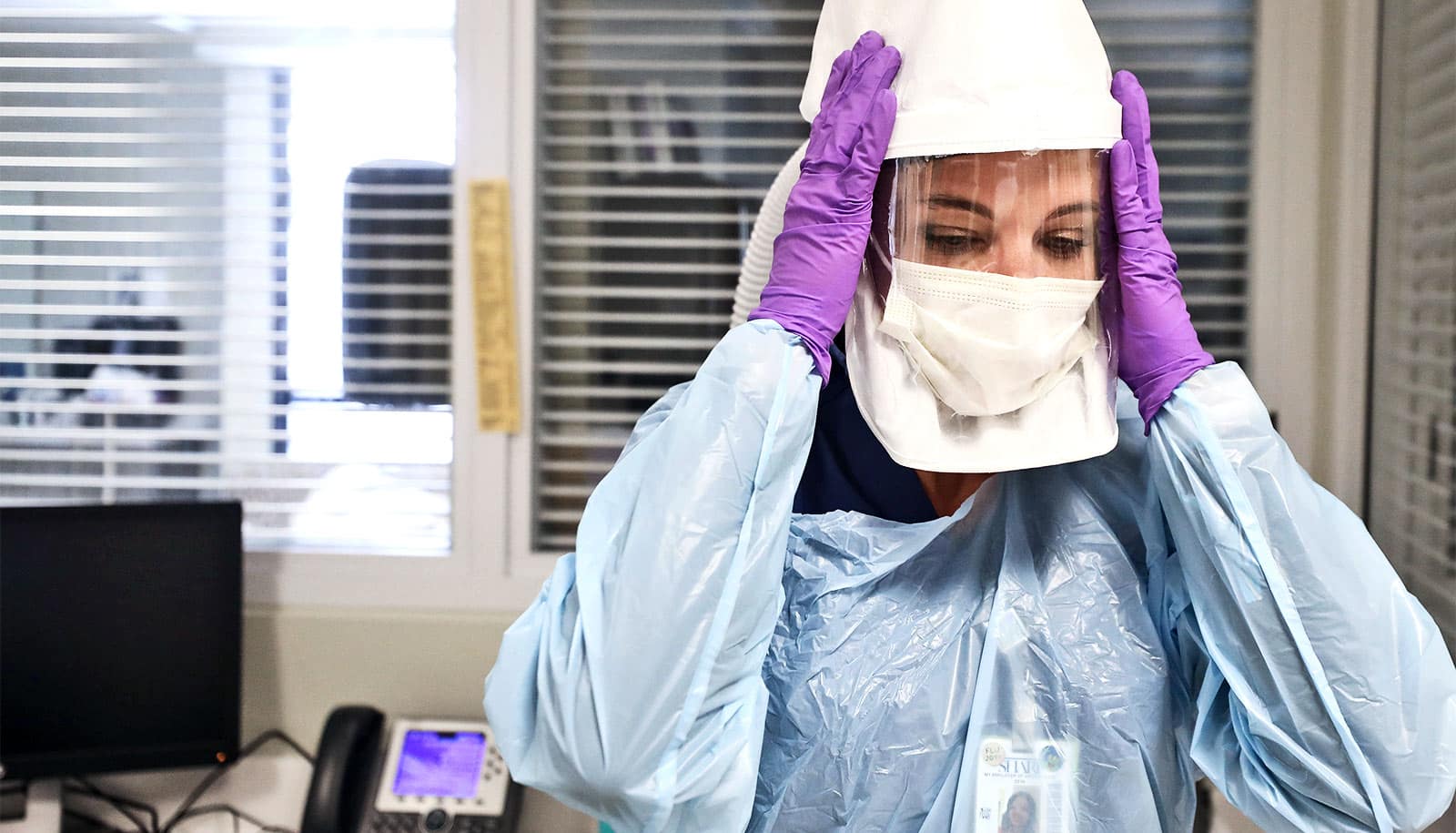

The mouth rinse is safer for health care workers, too, because test subjects can collect their own samples without the need for a health care worker to administer the test.

“For the medical technicians collecting nasopharyngeal swabs for diagnostic PCR tests, it just seems better to take the coughing, sneezing, and close proximity out of the equation to reduce the risks to the brave people doing that vital work, yet still provide a highly sensitive test,” Worobey says.

User-friendly for kids

To reconstruct complete genomes from samples containing coronavirus, researchers have to amplify the genetic material—in other words, make copies in the millions—and then stitch them together like pages randomly torn from a book.

Worldwide, researchers have sequenced more than 100,000 genomes so far, with most being deciphered with a technique Worobey pioneered.

“It turns out sequencing many virus genomes works best if you amplify about 100 to 300 small sections of nucleotides, sequence them, then stitch them back together into a cohesive genomic sequence,” Worobey says. “We call it RNA jackhammering, because you tackle a big problem by applying a whole bunch of little blows to it.”

Worobey hopes that the saltwater gargle test lives up to expectations and might eventually be used not just for research purposes but also for public health and individualized clinical diagnostic testing on the University of Arizona campus and beyond.

He thinks the test could fairly easily scale up to collect and process hundreds or thousands of samples per day—something that is more difficult to accomplish with standard saliva test samples, which are more viscous and therefore can be difficult to process.

Even if it doesn’t end up replacing currently used methods, Worobey says it could be another valuable tool. And, he adds, this method of COVID test is particularly user-friendly for school-aged children.

“That is an application where I could really see huge benefit to a safe, inexpensive—but most importantly less invasive—sampling modality like this,” he says.

Source: University of Arizona