While the abrupt shift to digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged many kids, students of color and low-income students have fared worse than the general student population, according to a new study.

A recent analysis from the research firm McKinsey & Company found the pandemic has led to disproportionate losses in learning for students of color, exacerbating existing achievement gaps and potentially increasing the odds those students may drop out.

The report estimates that, on average, students could lose seven months of learning during the pandemic, compared to 10 months for Black students and nine months for Hispanic students.

A survey of US educators from the EdWeek Research Center also found that, compared to the wealthiest schools, the poorest schools are less likely to have technology access, less likely to offer instruction (in person or online) and more likely to have students go missing from class.

Tomeka Davis, associate professor of sociology at Georgia State University, studies race and class stratification in education. Here, she discusses how the pandemic affects these issues:

When schools began closing last spring, why did this have such a disproportionate effect on poor students and students of color?

Public schools in the US are generally underfunded, and yet one of the things that the pandemic has shown is how much schools do for kids, not just academically but outside of the classroom.

For example, when schools shut down it led to an increase in food insecurity, because when kids go to school, they get two meals a day. If low-income students aren’t in school, they might not get fed.

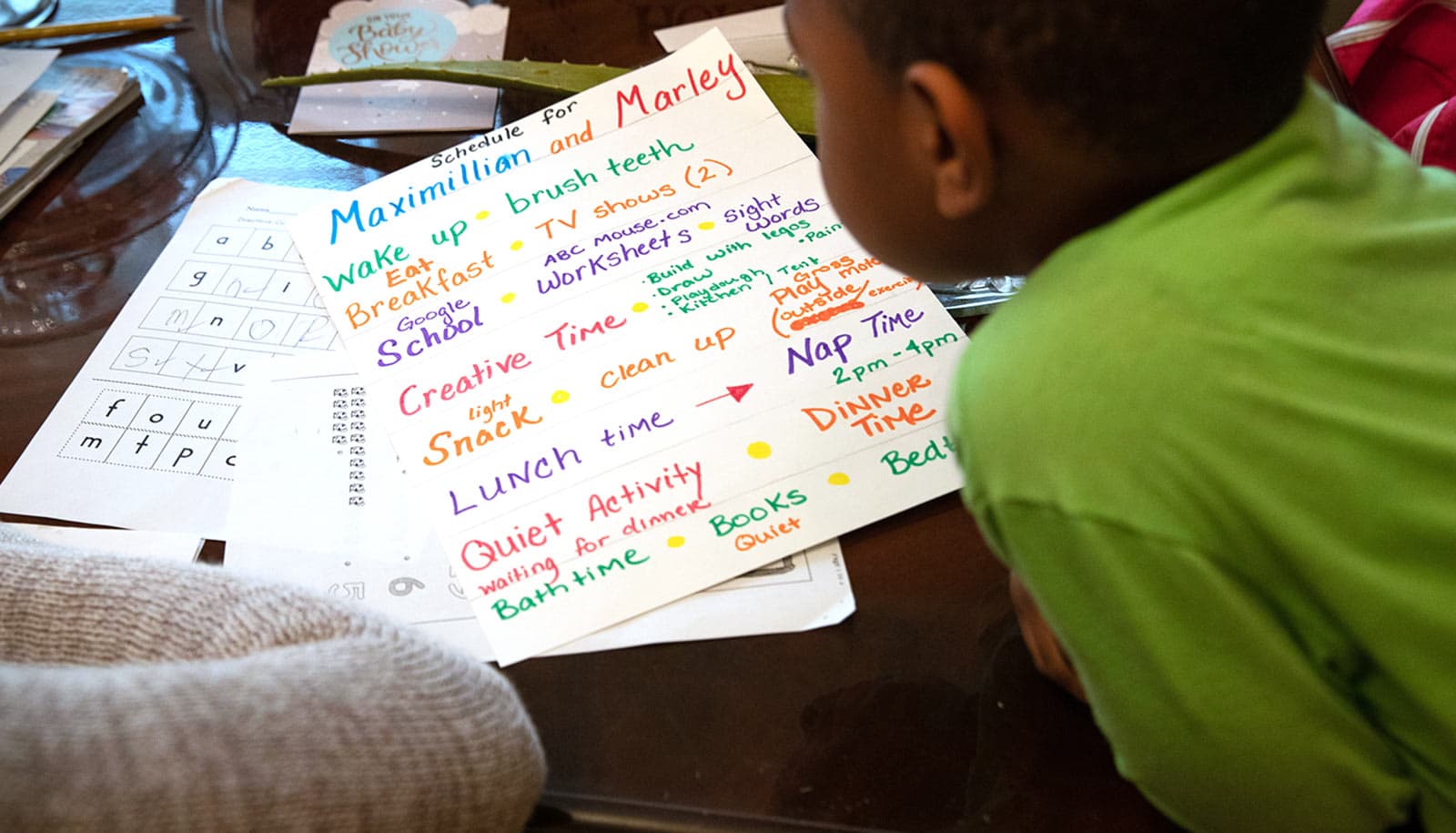

The digital divide has also played a role as schools scrambled to move to online learning. There are a lot of kids who don’t have home access to high-speed internet or digital devices other than maybe a mobile phone.

Research shows that the summer slide (the tendency for students to lose some of the gains in learning made during the previous school year) is worse for kids from low-income families. If you think about it, the same thing is happening when schools are closed due to the pandemic.

Poor kids often don’t have a home environment that facilitates learning, and now they’re at home all the time. Their parents may be essential workers or more likely to get sick. It’s a perfect storm on so many different levels.

How are disparities showing up again as schools consider how and whether to reopen in the fall?

One of the biggest barriers to in-person learning is large class sizes. If you go to a public school that, because of a lack of funding, has 30 or 35 students in a class, you can’t put those kids six feet apart.

Private schools especially can manage better because they often have much smaller class sizes. Even if there’s a hybrid model with at-home learning, students are going to have better access to their teachers if they only have 12 kids per class compared to 35 kids per class.

Other districts are talking about part-time schooling. My mother grew up during Jim Crow and she went to segregated schools. Back then, the government wasn’t interested in building schools for Black kids, so she and her brother went to school for only half a day because the school was so overcrowded that the kids essentially had to attend school in shifts. And this is what it sounds like again. It’s going to set kids back years.

The federal government has threatened to withhold federal resources from schools that do not re-open during the pandemic, allowing parents to take those dollars and use them via “school choice.” Could this help reduce disparities?

Based on what we know, no. This is a classic voucher argument: Parents should be able to take the dollars that they pay in taxes and use it wherever they want to send their kids to school. Yet research shows that these vouchers don’t do a good job of raising achievement at all. Using vouchers to move disadvantaged kids to a private school doesn’t help kids academically, and in some cases, it lowers their standardized test scores.

Experts believe there are a variety of explanations for disappointing impact of vouchers, including the lower quality of private schools who participate in voucher programs as well as high attrition rates in these programs.

What do schools need to serve all their students well during the pandemic?

I do think a lot of it is money. Going forward, we know that some schools can socially distance because of class size and other resources to implement safety measures, and those are the schools that can stay open. In the long term, we might need to retrofit existing school buildings or build more schools. If schools can’t open, we need broad, systemic investment to overcome the digital divide.

Kids and families also need a lot more in the way of social services, especially if schools can’t reopen. We ask schools to be everything for kids and we don’t give them the resources to provide it.

We shouldn’t have to worry about kids not having food because they have to get it in school. Or a parent having to quit their job because their child isn’t able to go to school. As a society, we are only as strong as our weakest link, and the pandemic has exposed a lot of weaknesses.

At some point, we hope the pandemic will end. How can the US help ensure that these equity issues are addressed and kids aren’t permanently left behind?

Parents want things to pick up where they left off, and yet kids have lost a lot of learning time and may need to be remediated. Legislatures have been cutting education budgets for years across the country, and that’s why you’ve seen all these teacher strikes on the news.

How are schools going to make up for these deficits, especially as budgets get even tighter because of a shrinking economy? Will schools—especially schools where there are already high levels of disadvantage—have the money to offer the kind of learning remediation that’s going to be required when this is over?

Public health experts have criticized the US’s response to the pandemic, and from an educational standpoint, I’m not sure that the post-pandemic response is going to be much better.

Source: Georgia State University