The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have negative consequences for the mental health of the people who get infected, the healthcare professionals caring for them, and the population as a whole, researchers report.

“It is known from the previous SARS epidemic in 2002-2003, also called the ‘bird flu,’ that mental health was affected among patients who survived the disease and among the healthcare professionals treating the patients,” says Michael Eriksen Benros, a professor in the immunology and microbiology department at the University of Copenhagen and the Mental Health Centre Copenhagen.

Benros is corresponding author of the new review of 43 scientific articles in Brain, Behavior and Immunity.

“Our recently published article systematically reviews current knowledge on symptoms among healthcare professionals and patients, and the same appears to be the case for the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Does COVID-19 infection affect mental health?

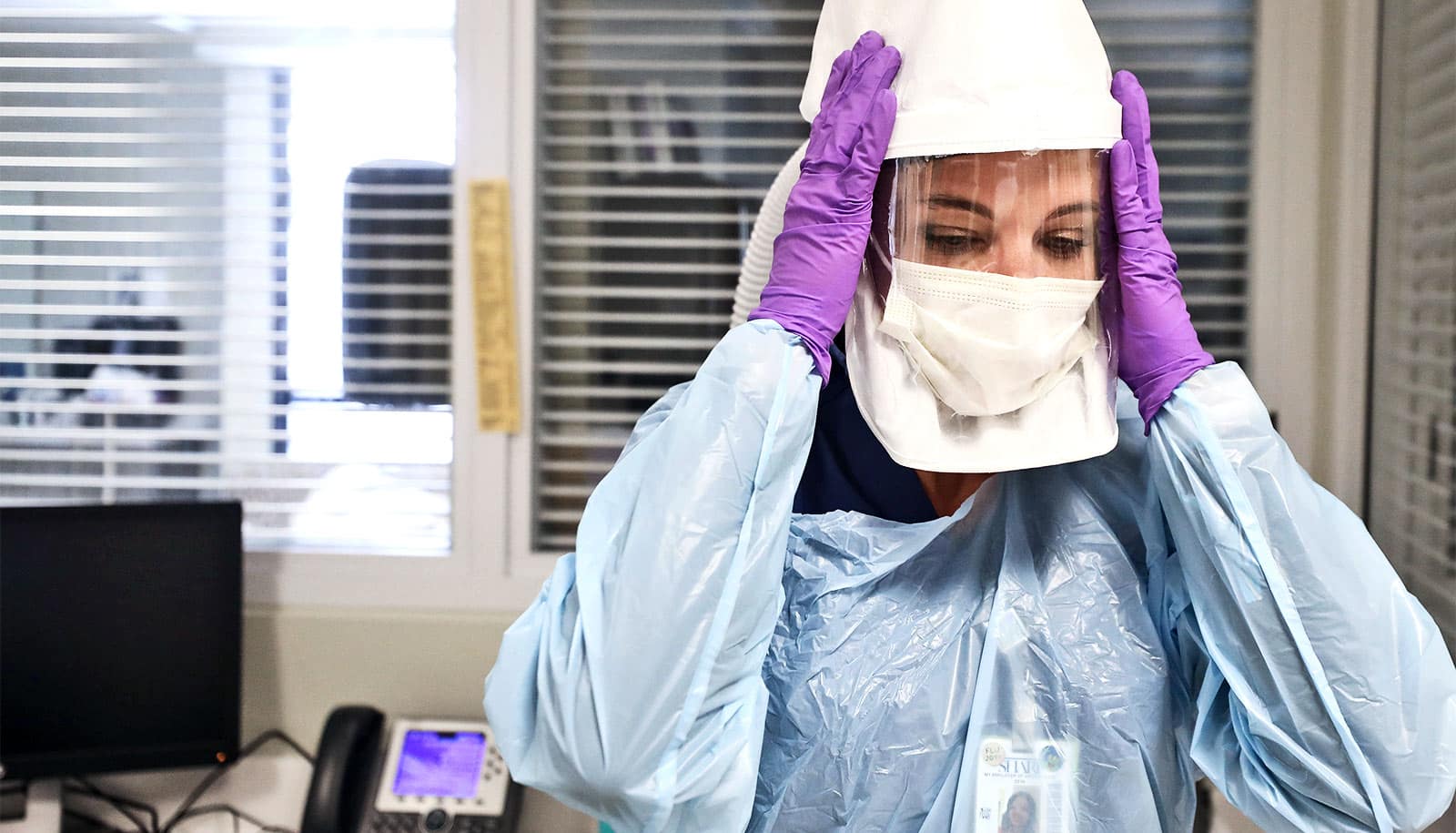

Of the 43 scientific studies, 20 studies examined the mental health among health care professionals. A majority of the studies found higher levels of anxiety and depression as well as mental stress and poor quality of sleep.

Nineteen studies examined the mental health of the population as a whole. Here, too, it is the overall picture that the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be having a negative impact.

“Given that the previous SARS epidemic was also associated with mental symptoms, we believe that research in this area is extremely important…”

Only two studies have so far examined mental symptoms among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The studies showed that 96% of seriously ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection exhibited symptoms of post-traumatic stress. They also found an increased risk of developing depression after hospitalization with COVID-19.

“Many more and better studies are needed, but the results are still relevant. The numerous reports of decreased sense of smell and taste during a COVID-19 infection might indicate an effect on the nervous system. It is therefore worrying that mental symptoms have been detected during and immediately after the infection,” says Benros.

“One contributing factor might be that the infection has affected the brain and caused the symptoms, either directly or through the induced immune response.”

More research is necessary

The researchers behind the review emphasize that significant reservations must be made because the included studies are of varying quality.

The urgent societal and health crisis has led to faster than usual publication of scientific articles. In addition, most of the studies have been performed as online questionnaires and therefore do not have the same quality as thorough, clinical studies. Also, most studies are from Asia, and it is unclear whether the results can transfer to an international context.

“We need more high-quality studies to make any final conclusions about a link between mental symptoms and COVID-19. However, our results indicate that COVID-19 may have an impact on the brain of those infected, and that there are derived effects of the pandemic on the mental health among both healthcare professionals and the population,” says first author, Nina Vindegaard Sørensen, a PhD student from the immunology and microbiology department.

“Given that the previous SARS epidemic was also associated with mental symptoms, we believe that research in this area is extremely important, as knowledge is a prerequisite for dealing with any mental consequences of COVID-19.”

The previous SARS epidemic spread to 28 countries and sickened around 8,000 people, while eight million people in over 180 countries and regions have already been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Additional researchers from the University of Copenhagen, and the Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, and Mental Health Services in the Capitol Region of Denmark contributed to the work.

Source: University of Copenhagen