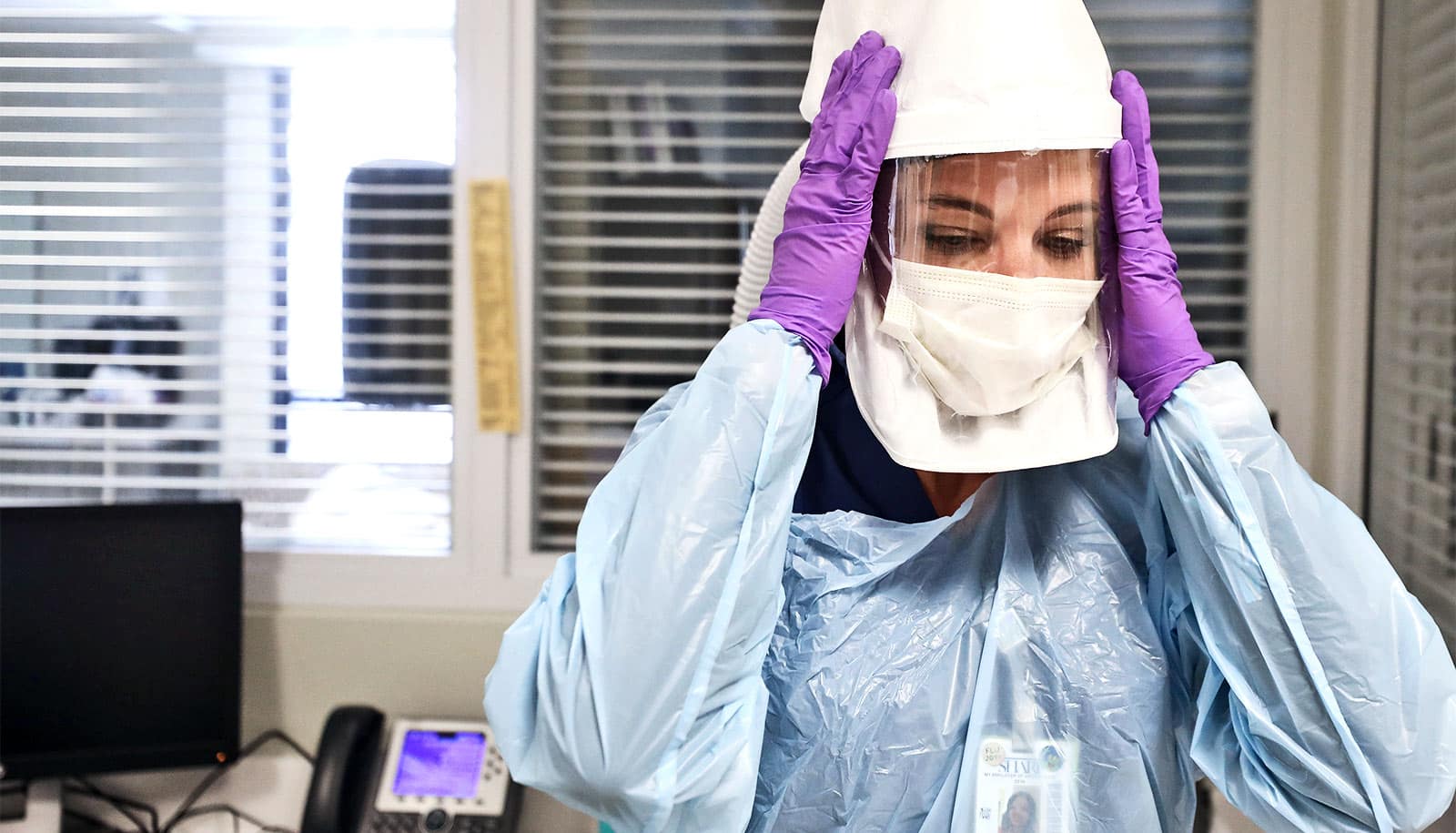

COVID-19 health care workers who care for hospitalized patients are at risk for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress, Maureen Brogan argues.

The unprecedented level of stress frontline health care workers face—separated from loved ones and often unable to process their own feelings during the global coronavirus pandemic—may lead to long-term mental health issues, says Brogan, the statewide program manager for the Traumatic Loss Coalitions for Youth Program at Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care.

“Any traumatic event may invoke grief, loss, anger and depression. In a pandemic, unlike with other traumatic events, the dangers are often invisible,” she says.

Here, Brogan explains how frontline workers can care for their own mental health while caring others:

What mental health concerns do frontline workers face now and after the pandemic?

A study published by the Journal of the American Medical Association on the mental health outcomes of health care workers attending to COVID-19 patients in China found that more than 70% reported psychological distress, 50% reported symptoms of depression and anxiety, and 34% experienced insomnia.

To minimize the stress after the crisis is over, these workers will need time to transition back to their normal day-to-day responsibilities. They and their loved ones should expect needing some time to readjust. They should not keep too busy, but allow time to process what they have been through.

They will need to be mindful of their use of alcohol and not make any immediate life-changing decisions such as moving or changing jobs. Services such as stigma-free counseling, workshops on stress management, and self-care should be available and promoted.

How can health care workers and first responders manage their daily stress?

First responders have been trained to be resilient in stressful environments and maintain their mental focus. They can support these skills through breathing techniques and “grounding” activities.

They should maintain physical activity, connections to others, eating healthy, and getting rest. Working in a supportive, non-judgmental “we are all in this together” environment is also helpful. If they identify symptoms of depression, they should seek professional help.

How can they manage the emotions that accompany working during a pandemic?

Frontline workers face losses outside of their control and do not have the time to grieve. They must focus on what they can control—self-care, staying connected—and give themselves permission to feel and talk about the pain they experience.

They can remember that they are taking actions to keep their families safe while they do their job and soak up the positivity from the community: the shift-change applause, the meals being delivered to the hospitals, the messages of hope sent from children.

How can frontline workers maintain family relationships while apart?

Using social media platforms to stay connected will never replace a hug, but it reminds us that the heart is not separated by physical boundaries.

Children should keep their routines and family rituals to maintain a sense of predictability. While first responders cannot promise their families that everything will be okay, they can share all the steps they are taking to keep safe.

In what ways can the community show support for frontline workers?

The public can donate supplies, give social media shout-outs, assist with child care, have healthy meals delivered, donate blood, and, most importantly, follow CDC and local safety guidelines.

What mental health resources are available for frontline workers?

The Disaster Distress Helpline, 800-985-5990, provides counselors for people during a crisis, and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 800-273-TALK (8255) provides support for callers, whether or not they are suicidal.

Source: Rutgers University