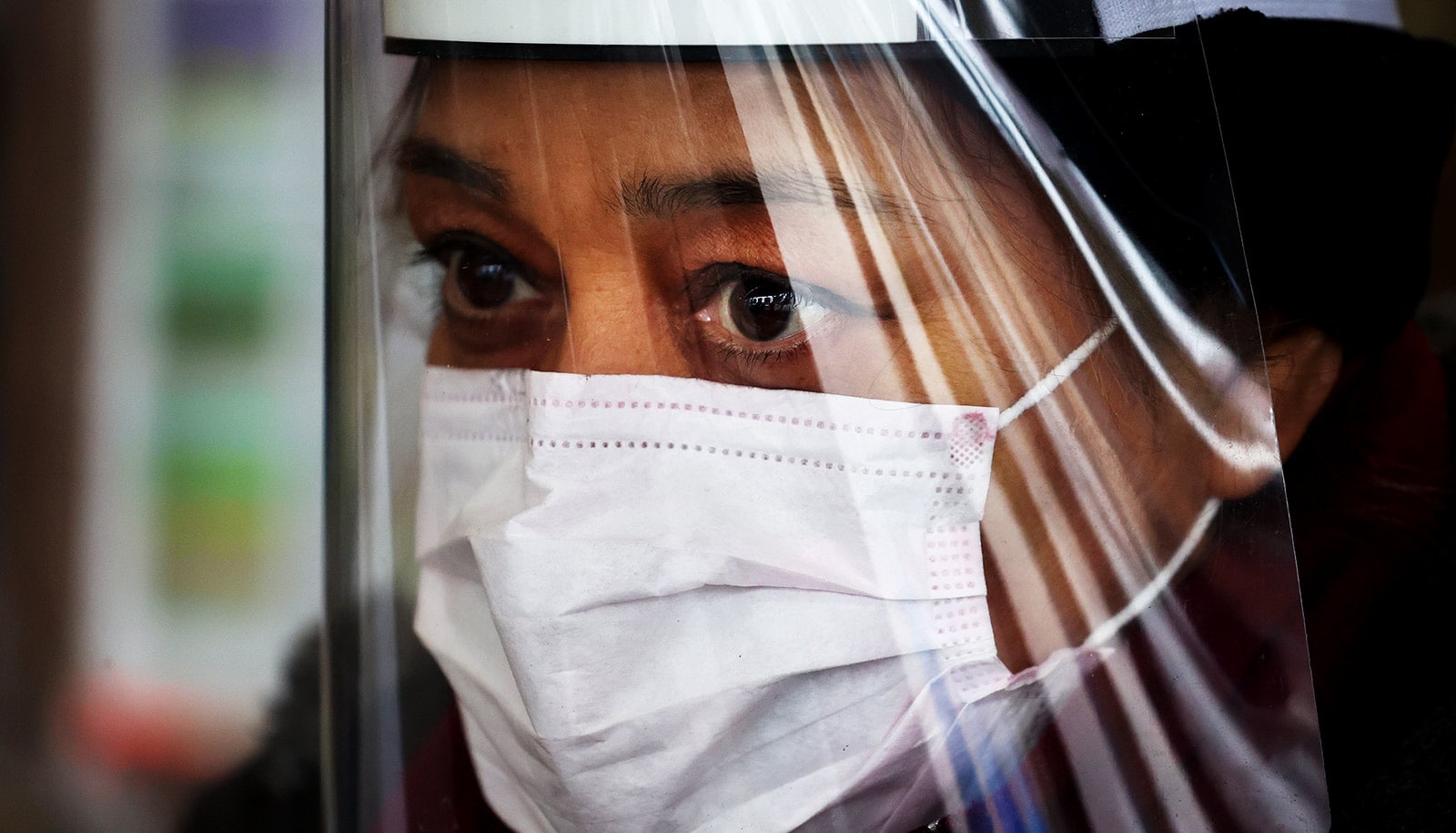

Controlling COVID is essential to restoring the economy, Lisa Kahn says

In a typical recession in the US economy, most job losses are permanent. Only a small percentage are considered temporary, where a worker can reasonably expect to be called back.

“The shutdowns are not what have been driving the economic collapse; it’s the global pandemic.”

But Kahn, a professor of economics at the University of Rochester, says the COVID-19 recession is anything but typical.

Temporary unemployment reached a high of around 80% during the COVID-19 recession. That peak, from last May, declined as expected—until progress stalled in controlling the spread of the virus.

Rebutting assertions that lockdowns have put a drag on the economy, Kahn says, “The shutdowns are not what have been driving the economic collapse; it’s the global pandemic.”

While vaccinations are accelerating in many places, we live in a global economy. There is still a long way to go to get past the COVID recession. And when we do, the recovery may look different, too.

Kahn’s insights are based on a study in which she—along with fellow economists Eliza Forsythe of the University of Illinois, Fabian Lange of McGill University, and David Wiczer of Stony Brook University—documented the evolution of the labor market from mid-March through November 2020.

Here, Kahn explains the COVID-19 recession and what the world could look like in the future:

What’s different about the COVID-19 recession?

In April, 20 to 30 million people were separated from their jobs and roughly 80% of them were placed on temporary layoff. What typically happens in a recession is that people permanently lose their jobs. In this case, people expected the shock to be temporary—maybe two weeks or a month. Over the rest of the year, we think that group was steadily recalled back to their previous employers, and that has been a very good thing. Unfortunately, we have seen much less progress among the group who was permanently separated from their previous employers. That group grew over the summer, is now sizable, and has shown no net progress in terms of returning to the workforce. I’m definitely concerned about how that group will fare once employers start hiring again in earnest.

The dramatic thing about the COVID crisis was the sharp spike in unemployment. The job losses in earlier recessions look like blips in comparison.

What’s the relationship between state lockdowns and the collapse of the economy?

The shutdowns are not what have been driving the economic collapse; it’s the global pandemic. In New York State, the movie theaters started opening, but I don’t think many people have been going to the movies. People decide for themselves whether they want to leave their homes to consume during such a risky time.

We saw this in May and June when COVID cases waned and we had a rapid economic recovery—we got back half the jobs we lost during the first wave. But in July, when we had our second increase in COVID cases, everything stopped, and the recovery has been moving sideways ever since. These additional COVID waves have prevented the economy from recovering in earnest, even though there have been relatively few state-imposed restrictions on behavior.

What will the labor market look like when the pandemic begins to wane?

We estimate that roughly 5 million workers will need to be matched to new employers. What does that number depend on? There’s a growing set of people who report they’re looking for work but don’t have connections to previous employers. In addition, workers on temporary layoff who were waiting for their employers to recall them may stop waiting, their employers may go out of business, or they may get sick of waiting. On top of that, there are a lot of people sitting out of the labor market who are neither searching nor waiting for employers to call them. This is also unique to the COVID recession. People are worried about the virus, or can’t leave home right now because they may have family members with a preexisting condition, or are required to be a primary caregiver to their children. Once COVID is no longer a factor, these groups will need to find new jobs as well.

In what ways are jobs changing?

In previous research, I showed that recessions are an opportune moment for employers to change how they produce. In the Great Recession, many employers took the opportunity to restructure their processes toward cheaper, labor-replacing technologies, and they consequently laid off certain sets of workers in favor of machines. Those employers then needed a different type of worker to help operate those machines. Think of grocery stores that installed self-checkout machines. The technology existed before the Great Recession, but was not widely adopted until then. That’s one reason we had a jobless recovery at the time.

We expect something similar might happen following the COVID recession. Employers might be especially concerned about relying too much on in-person activities and desire to shift towards remote work. The economy as a whole might shift towards products that can be consumed remotely (such as Netflix, Amazon, and Instacart).

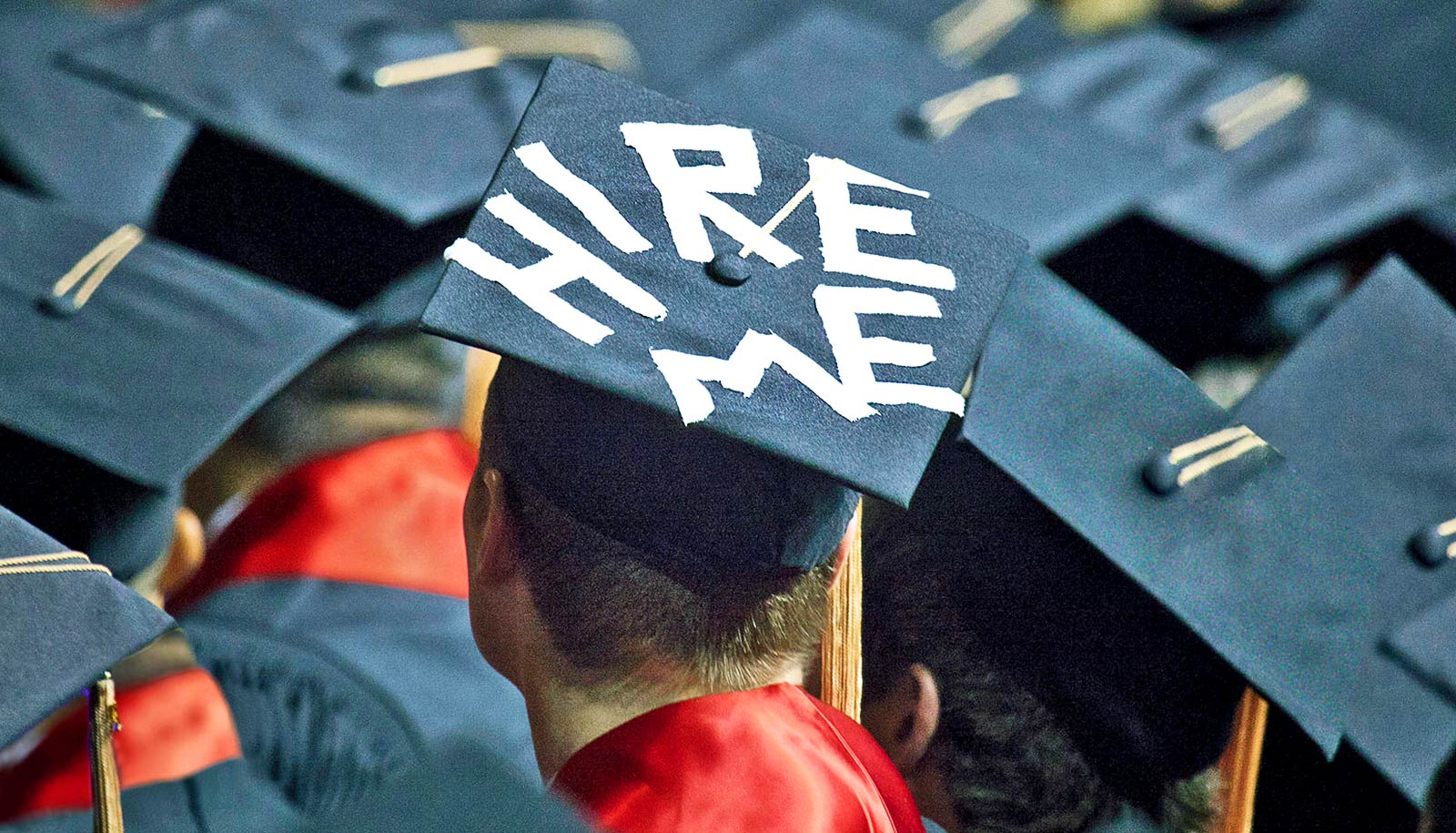

What does all this mean for college graduates?

New college graduates who enter the economy during a recession face long-lasting earnings consequences.

While it’s a stressful time to be entering the job market, college graduates can typically find employment, but it often means taking jobs with limited opportunities. One thing people can do in the long run is always be thinking about whether their current opportunities are the best ones for them. Is it the best fit? Are they fulfilled? Are they happy in the job? Or should they consider moving on when the economy picks up? The data suggest that people who graduate and join firms in a recession get stuck in those jobs and don’t move around as often as young people should—something that’s good for career advancement.

Is there anything college seniors can do to better position themselves during the COVID recession?

In the short run, a good option for graduates could be to delay the job market by a couple of years. By going to graduate school, they might be able to recover the lost ground of entering the job market during a recession. There are, however, some cautionary tales. In the Great Recession, graduates tended to flock to non-specialized areas—like law schools—that don’t have many barriers to applying. Law schools were happy to make money, so they admitted many more students, which led to an oversupply of new young lawyers. And three years after the Great Recession, the economy was still in a bad position, and new lawyers tended to suffer.

For those who will be entering the labor market, they should be willing to take a job, no matter what it is. It looks better on your resume to be doing something than not doing something. But they should work hard to ensure they don’t get stuck in that position (unless they end up loving it!).

We hope we’ll come out of the COVID recession more quickly than we did the Great Recession. It all depends on getting the virus under control and people not being reluctant or unable to consume.

Source: University of Rochester