Under the right living arrangement, disease-resistant corals can help “rescue” corals that are more vulnerable to disease, according to a new study.

For the study in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers monitored a disease outbreak at a coral nursery in Little Cayman, Cayman Islands.

The finding shows that when people grow corals of the same genotype—or genetic makeup—together, those corals are more vulnerable to disease than corals that grow among a mixture of genotypes. The study further found that some vulnerable corals can be “rescued” by resistant genotypes.

“We saw that some corals were more resistant to disease just by being around other corals that were particularly resistant,” says lead author Anya Brown, an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, Bodega Marine Laboratory in the evolution and ecology department. “Proximity to these resistant genotypes helped buffer the susceptible corals from the effects of the disease.”

Mixed corals are more resistant to disease

The findings provide further evidence that genetic diversity can help reduce disease transmission among corals, while also showing that it’s important to consider how corals are arranged in nurseries and reef restoration projects to prevent the spread of disease.

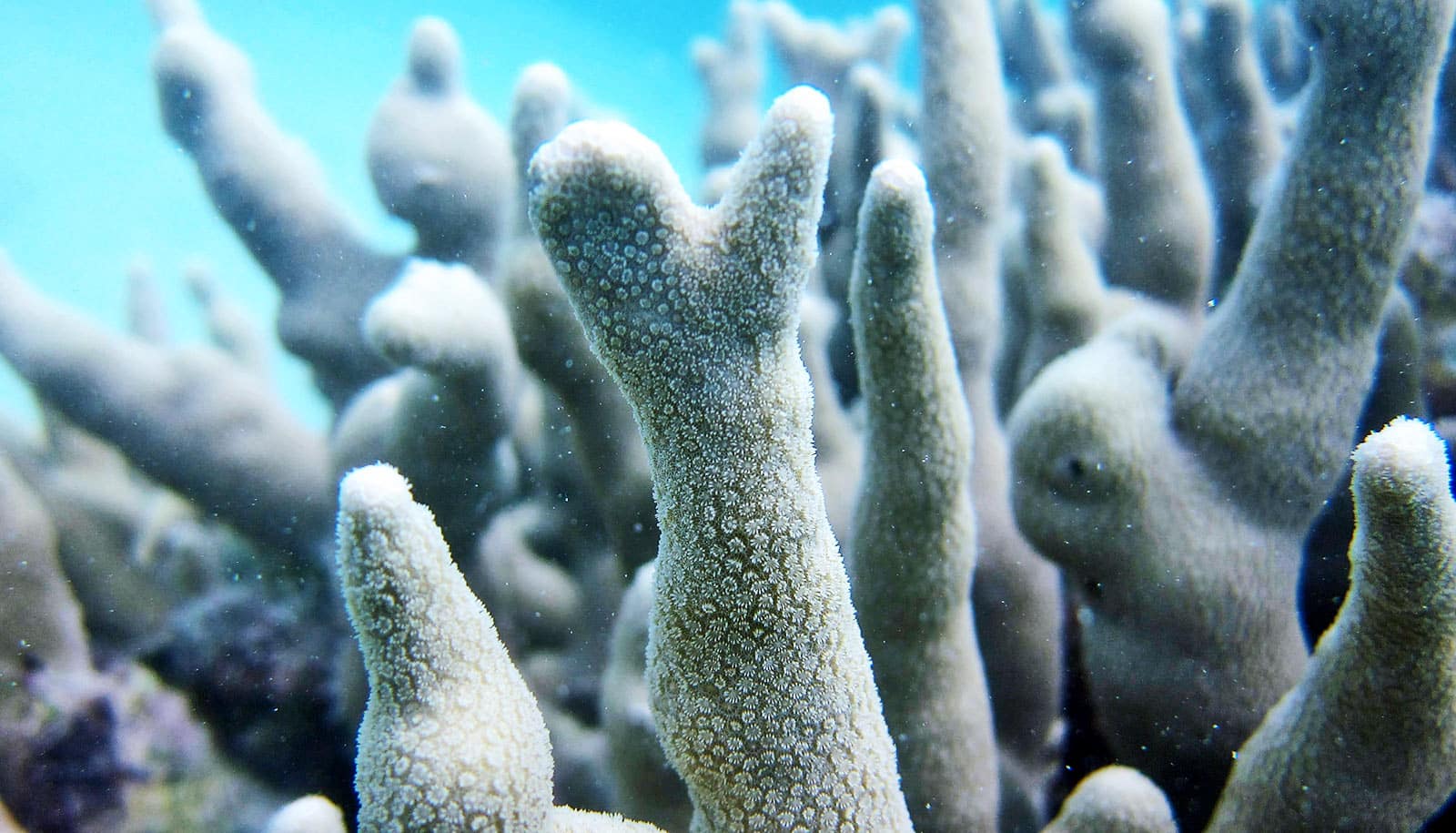

After an outbreak of white band disease spread through its coral nursery in Little Cayman, the nonprofit Central Caribbean Marine Institute worked together with the study’s academic authors to monitor its population of endangered Caribbean staghorn coral, A. cervicornis.

Before the outbreak, the nursery had attached coral fragments to plastic PVC frames to propagate them. Some frames held coral from a single donor colony. Other frames hosted corals from multiple donor colonies representing a mixture of genotypes.

After tracking the presence of the disease across 650 coral fragments for more than five months, the researchers found that corals living on frames with a mixture of genotypes were substantially more resistant to white band disease, a devastating bacterial disease that nearly wiped out A. cervicornis in the 1980s.

‘Vaccinated’ corals

The ability of resistant coral to help protect vulnerable individuals is similar to how vaccinations work among humans: Vaccinated individuals resist a disease, erecting a barrier that weakens its ability to move through them and on to the next susceptible person.

As for the genetic diversity piece, agricultural lands provide another comparison: Monocrops, where the same crop is planted in the same place each year, tend to be more susceptible to disease than diverse systems. This research suggests a similar dynamic is at play among the ocean’s coral reefs.

Brown hopes these concepts and this study will be integrated into coral nursery and reef restoration projects.

“I hope people working with coral nurseries use this as a springboard to see how this influences the spread of disease,” Brown says. “Nurseries that intentionally arrange corals with mixtures of genotypes can help corals vulnerable to disease thrive. This can help build coral resilience by repopulating reefs with a diverse genetic mixture of corals.”

Additional coauthors are from Central Caribbean Marine Institute, the University of Florida, and the University of South Florida.

The John H. and Katherine C. Ewel Fellowship, the University of Florida, and the Central Caribbean Marine Institute funded the work.

Source: UC Davis