Coral nurseries, which provide coral fragments for transplantation in barren areas, could also help in the conservation of threatened species, researchers report.

This bit of good news came from the final-year project of Crystle Wee, who earned a bachelor of environmental studies from the National University of Singapore. She worked on the paper in the Journal for Nature Conservation with Chou Loke Ming, emeritus professor at NUS Biological Sciences, and Toh Tai Chong from the College of Alice & Peter Tan.

The study followed in the wake of an earlier project started in 2013 by a team Chou and Toh led, which saw six hard coral species successfully transplanted onto artificial seawalls on Lazarus Island off the southern coast of Singapore.

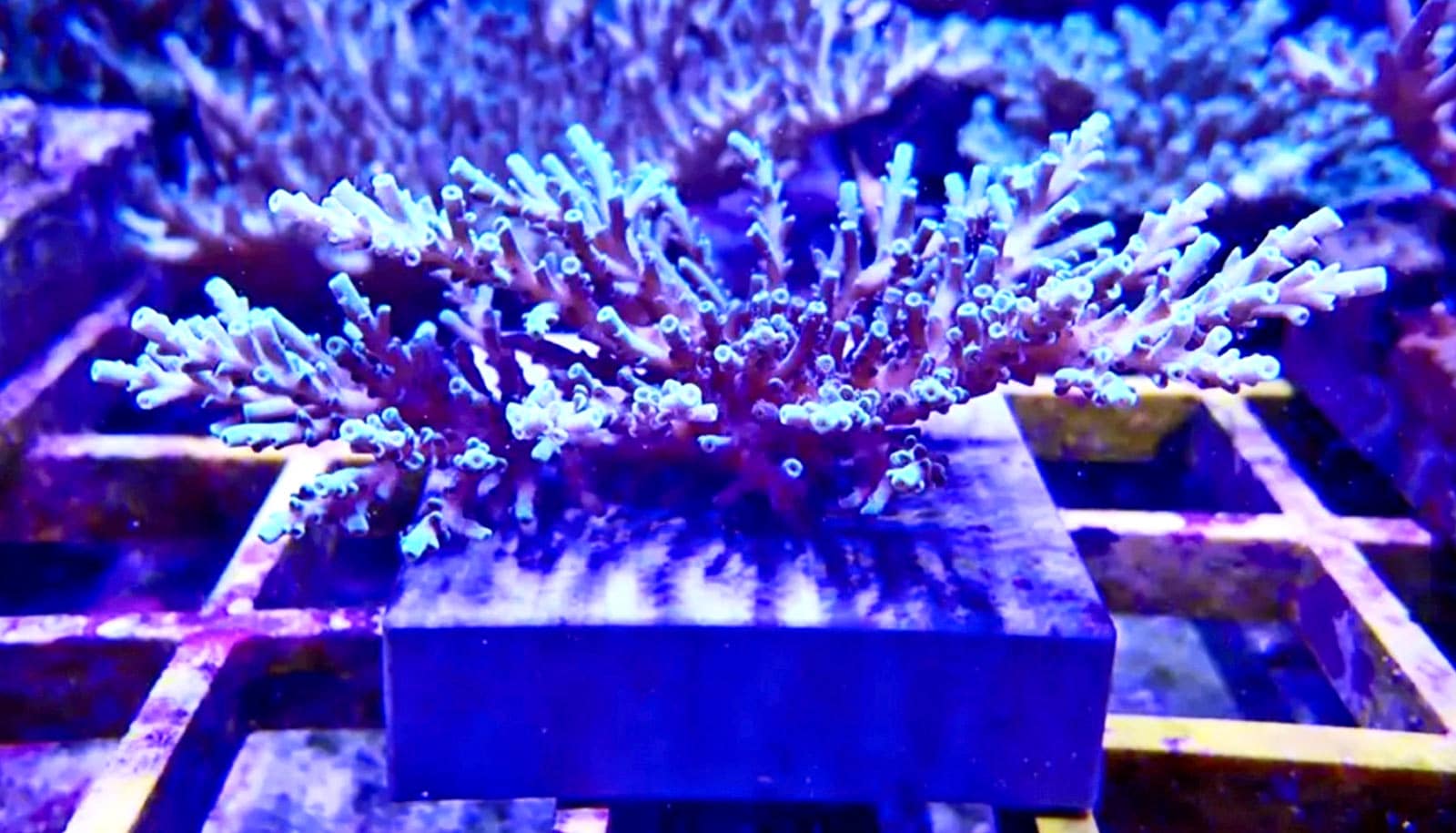

For the new study, researchers used fragments from corals growing off Kusu Island in Singapore. Researchers reared the fragments in the ocean, with each fragment, about the length of a human finger, placed on mesh nets or plastic pipes. The team can then transplant the fragments to degraded reef areas in six to 12 months.

The findings show that corals can get a second lease on life and that it’s possible to create a sustainable marine environment even in urbanized coastal areas.

Human-made structures such as seawalls and breakwaters are increasingly erected to reduce the effects of rising sea levels brought on by climate change. More than 60% of urban Singapore’s approximately 124 miles (200 kilometers) of shoreline consists of seawalls. The corals grown on these seawalls have shown sustained growth as well as high survival rates of close to 90% on average.

The new study also shows that underwater nurseries don’t just provide coral materials for future transplanting but also shelter and fodder for marine organisms. Researchers have found sea creatures like crabs, brittle stars, and sea slugs within the live corals of the nurseries.

“Our findings showed that coral nurseries can support a range of mobile invertebrates and function as tools to conserve threatened mobile invertebrates. This ecological function is understudied and should be assessed in restoration programs for the conservation of corals and associated fauna,” the team writes in the paper.

The findings could provide insights for future reef restoration projects, says Chou.

“The next step would be to develop approaches to engineer our coastlines sustainably, so as to balance our economic needs and conservation of our natural environment,” adds Toh.

Source: NUS