Local efforts to round up predatory snails can significantly boost the resilience of corals to climate-induced bleaching, a new study reports.

The findings come at a time when scientists are deeply divided over whether local conservation actions to protect and manage coral reefs are enough to help stem the global tide of thermal bleaching that’s decimating corals worldwide as ocean temperatures continue to warm.

To test whether work like this can make a difference, researchers focused on one threat to reefs that is often controlled by local managers—populations of coral-eating animals like snails and starfish that have become too abundant.

Like Dracula

“The idea was to see if removing these snails helped corals withstand and recover from warm temperatures and bleaching… And it did.”

“At high densities, these coral-eating animals, or ‘corallivores’, can cause low-grade but chronic stress to corals,” says Elizabeth Shaver, a 2018 doctoral graduate of Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, who is now a coral restoration scientist with The Nature Conservancy’s Reef Resilience Program.

“Some of them are like Dracula, constantly sucking the energetic reserves out of corals and leaving them less equipped to deal with harsh environmental conditions like extreme warm temperatures and bleaching.”

To get a global sense of how managers deal with this threat, researchers surveyed more than 30 coral reef management agencies worldwide, finding that many reduce local corallivore populations in their sites. The researchers then mimicked managers by manually removing a voracious and common coral-eating snail from corals in the Florida Keys during a three-month spike in ocean temperatures in 2014. That warmup caused widespread coral bleaching across much of the eastern Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

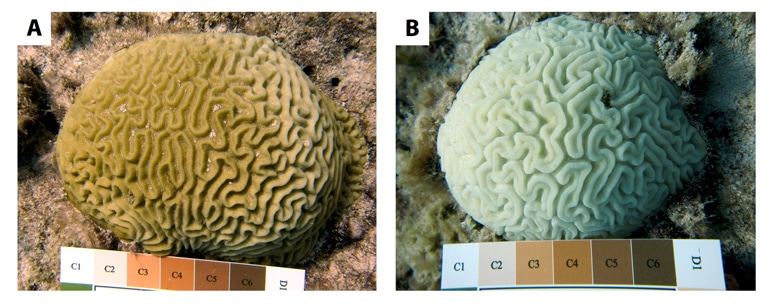

The researchers focused their efforts on brain corals, which were found in a survey of six corals reefs in the Florida Keys to be particularly susceptible to predation by the snail.

“The idea was to see if removing these snails helped corals withstand and recover from warm temperatures and bleaching compared with corals that had average or naturally high densities of snails. And it did,” Shaver says.

“When snails were removed, corals experienced only 50 percent bleaching. Corals that still had high snail densities experienced near 100 percent.”

Underwater basketballs

In November 2014, they returned to the reefs after water temperatures cooled down and measured the extent of dead tissue on the corals.

“We found that if a coral experienced only mild to moderate bleaching, as they did when snails were removed, it recovered almost completely,” says Brian Silliman, associate professor of marine conservation biology.

“But if it experienced severe bleaching like the corals with high snail densities, tissue recovery was reduced by more than 80 percent,” he adds. “Some of these corals completely died, turning into algae-covered underwater basketballs. Removing or reducing the populations of snails played an important role in determining these outcomes.”

The new findings, which appear in Nature Ecology & Evolution, challenge several recent large-scale analyses arguing that local impacts and management have little effect in protecting reefs from climate-induced bleaching, Silliman says.

“Tens of millions of dollars have been invested in local coral reef conservation over the last 40 years. But more and more people are now saying we should end this approach and instead put most of our money into global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions because there’s no evidence that local actions are making enough of a difference.

“These new findings reopen the discussion and provide a ray of hope for corals by showing that local interventions do make a difference.”

Watch: Plastic trash makes diseases worse for corals

“Very few local interventions have been tested for their ability to enhance coral reef resilience,” Shaver says. “We found one simple solution by reducing coral predation stress, which can be done through removals or possibly in marine protected areas where studies show coral-eating invertebrates are naturally less abundant.”

The findings may also be important because the world’s climate is projected to continue changing even if carbon emissions were drastically reduced today.

Invasive snails jump ship at first whiff of a predator

“We need conservation dollars for both global and local efforts,” says Shaver, “so we can identify other resilience-enhancing approaches and arm local managers with tools to protect their reefs and resources.”

Deron E. Burkepile of the University of California, Santa Barbara, is coauthor of the study. The National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: Duke University