Researchers have documented an entirely new class of fire, spherical cool diffusion flames, appropriately referred to as “cool flames.”

Creating this unique fire required an equally unique laboratory: the microgravity environment of space. Researchers documented these dim, quiet flames aboard the International Space Station.

“The Space Station is a lab like no other,” says Richard Axelbaum, professor of environmental engineering science in the energy, environmental, and chemical engineering department in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Being able to perform experiments in microgravity allowed us to observe a flame that just would not exist on Earth. This type of discovery is what makes the Space Station so invaluable to scientific exploration.”

The discovery itself transforms researchers’ understanding of what fire can be and what fire can do, says lead researcher Peter Sunderland, a professor at the University of Maryland.

“The goal of our research is to understand the particular processes ongoing in spherical cool diffusion flames. If we can understand and model how they work, then we might be able to harness cool flames to design a new class of clean combustion engines.”

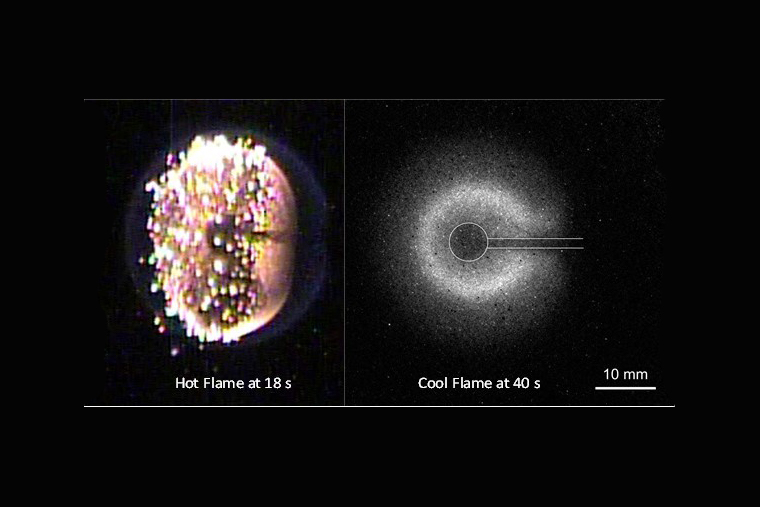

First observed during an experiment burning a fuel droplet aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in 2012, the cool flames appeared only briefly before the liquid fuel was depleted. The sighting catalyzed an emerging, rapidly growing field in combustion research.

The flames are also somewhat mysterious: As recently as 10 years ago, researchers had only theoretically predicted them.

In these new experiments, researchers observed cool spherical gaseous flames for the first time. Cool flames burn at extremely low temperatures and are nearly invisible. For comparison, a natural gas flame on a conventional stove top can burn at around 3100 degrees Fahrenheit (1700 degrees centigrade); a typical cool flame hovers around 950 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees centigrade).

“Little is known about combustion chemistry at these low temperatures,” Sunderland says. “Part of what we’re learning is how much we didn’t know.”

The project to understand cool flames is one of two that Axelbaum is involved with on the International Space Station. He leads the other project, also a collaboration with Sunderland, working to design soot-free flames.

Additional researchers from the University of California, San Diego; the University of Maryland; and Washington University in St. Louis contributed to the work.

The experiments were performed as part of the Cool Flames Investigation with Gases (CFI-G) project, which gets support from the NSF, NASA, and CASIS.