New micron-sized calcium silicate spheres could lead to stronger and greener concrete, the world’s most-used synthetic material.

To researchers, the spheres represent building blocks that can be made at low cost and promise to mitigate the energy-intensive cement-creation techniques. Cement is the most common binder in concrete.

“Cement doesn’t have the nicest structure…”

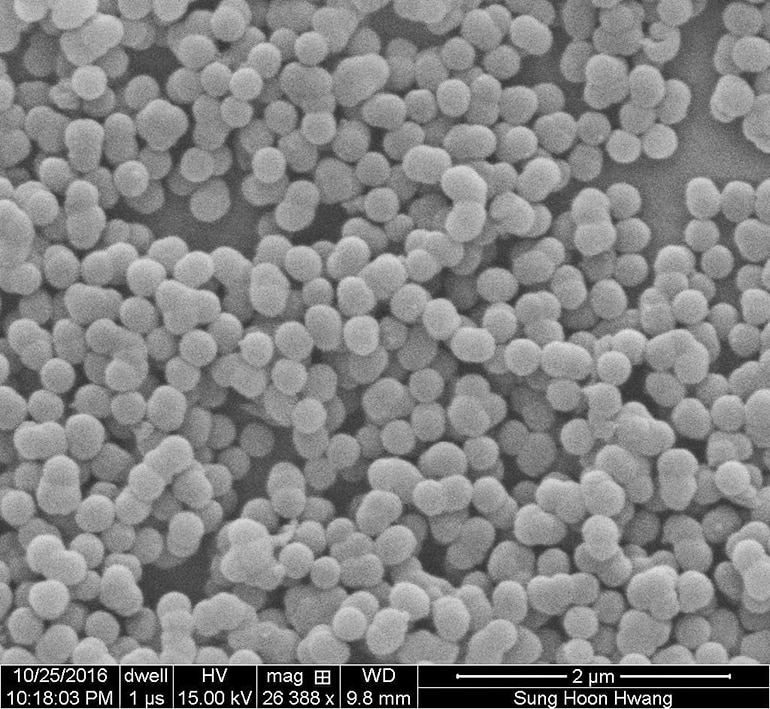

The researchers formed the spheres in a solution around nanoscale seeds of a common detergent-like surfactant. The spheres can be prompted to self-assemble into solids that are stronger, harder, more elastic, and more durable than ubiquitous Portland cement.

“Cement doesn’t have the nicest structure,” says Rouzbeh Shahsavari, an assistant professor of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice University. “Cement particles are amorphous and disorganized, which makes it a bit vulnerable to cracks. But with this material, we know what our limits are and we can channel polymers or other materials in between the spheres to control the structure from bottom to top and predict more accurately how it could fracture.”

The spheres are suitable for bone-tissue engineering, insulation, ceramic, and composite applications as well as cement, he says.

The work builds on a 2017 project by the researchers to develop self-healing materials with porous, microscopic calcium silicate spheres. The new material is not porous, as a solid calcium silicate shell surrounds the surfactant seed.

But like the earlier project, it was inspired by how nature coordinates interfaces between dissimilar materials, particularly in nacre (aka mother of pearl), the material of seashells. Nacre’s strength is a result of alternating stiff inorganic and soft organic platelets. Because the spheres imitate that structure, scientists consider them biomimetic.

“These are very simple but universal building blocks, two key traits of many biomaterials…”

The researchers discovered they could control the size of the spheres that range from 100 to 500 nanometers in diameter by manipulating surfactants, solutions, concentrations, and temperatures during manufacture. That allows them to be tuned for applications, Shahsavari says.

“These are very simple but universal building blocks, two key traits of many biomaterials,” Shahsavari says. “They enable advanced functionalities in synthetic materials. Previously, there were attempts to make platelet or fiber building blocks for composites, but this works uses spheres to create strong, tough, and adaptable biomimetic materials.

“Sphere shapes are important because they are far easier to synthesize, self-assemble, and scale up from chemistry and large-scale manufacturing standpoints.”

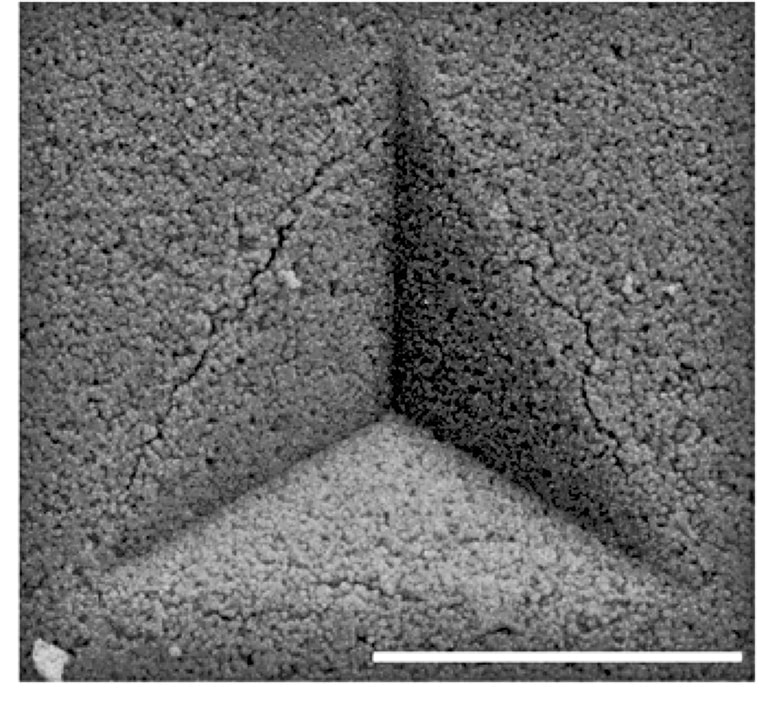

In tests, the researchers used two common surfactants to make spheres and compressed their products into pellets for testing. They learned that DTAB-based pellets compacted best and were tougher, with a higher elastic modulus, than either CTAB pellets or common cement. They also showed high electrical resistance.

Shahsavari says the size and shape of particles in general have a significant effect on the mechanical properties and durability of bulk materials like concrete.

“It is very beneficial to have something you can control as opposed to a material that is random by nature,” he says. “Further, one can mix spheres with different diameters to fill the gaps between the self-assembled structures, leading to higher packing densities and thus mechanical and durability properties.”

He says increasing the strength of cement allows manufacturers to use less concrete, decreasing not only weight but also the energy required to make it and the carbon emissions associated with cement’s manufacture. Because spheres pack more efficiently than the ragged particles found in common cement, the resulting material will be more resistant to damaging ions from water and other contaminants and should require less maintenance and less-frequent replacement.

The National Science Foundation and C-Crete Technologies LLC supported the research.

The study appears in the journal Langmuir.

Source: Rice University