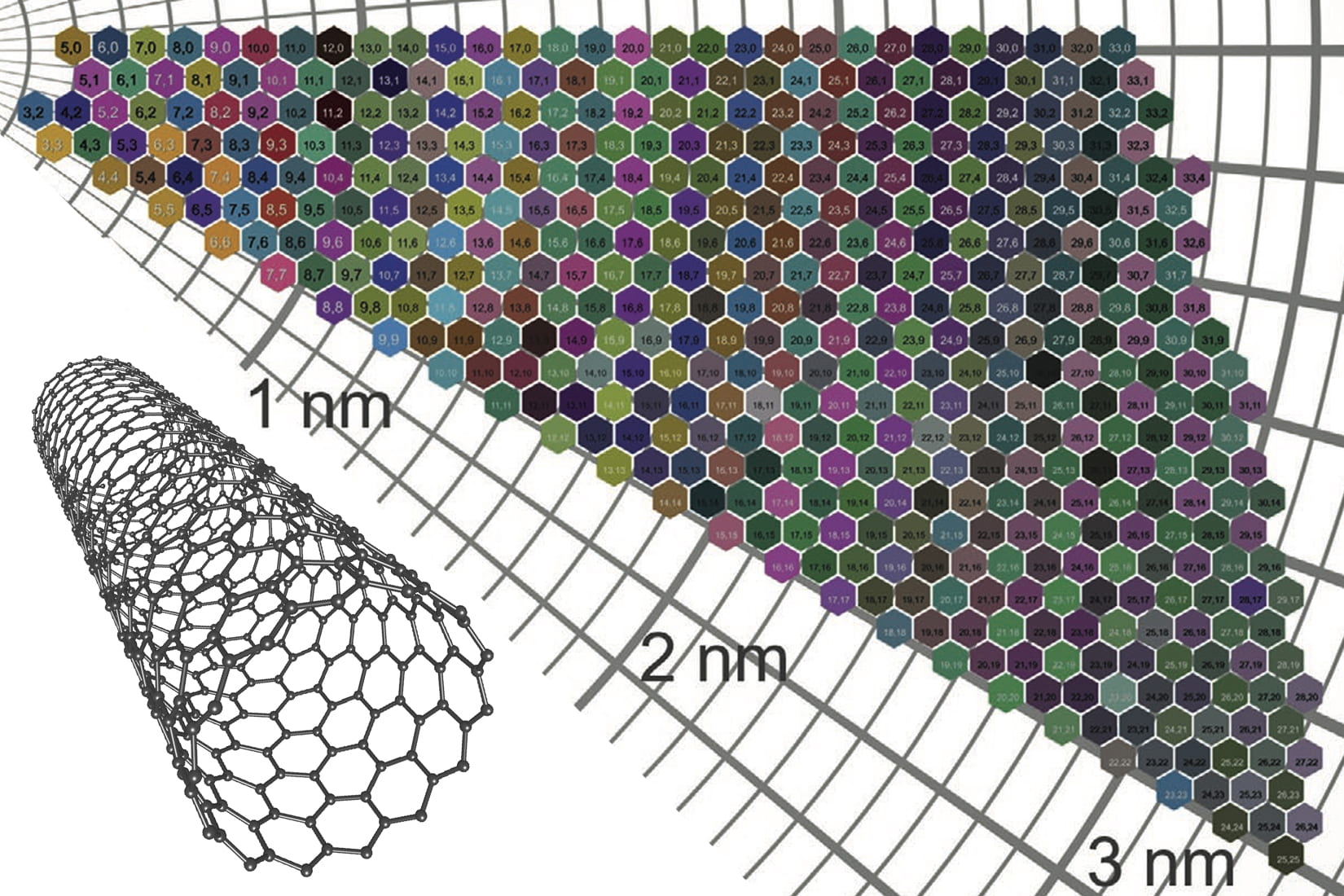

Researchers have created a color atlas for 466 unique varieties of single-walled carbon nanotubes.

The researchers detail the nanotube color atlas in a study about a new method to predict the specific colors of thin films made by combining any of the 466 varieties.

“Carbon, which we see as black, can appear transparent or take on any color of the rainbow,” says Esko Kauppinen, a physicist at Aalto University in Finland and corresponding author of the study in Advanced Materials.

“The sheet appears black if light is completely absorbed by carbon nanotubes in the sheet. If less than about half of the light is absorbed in the nanotubes, the sheet looks transparent. When the atomic structure of the nanotubes causes only certain colors of light, or wavelengths, to be absorbed, the wavelengths that are not absorbed are reflected as visible colors.”

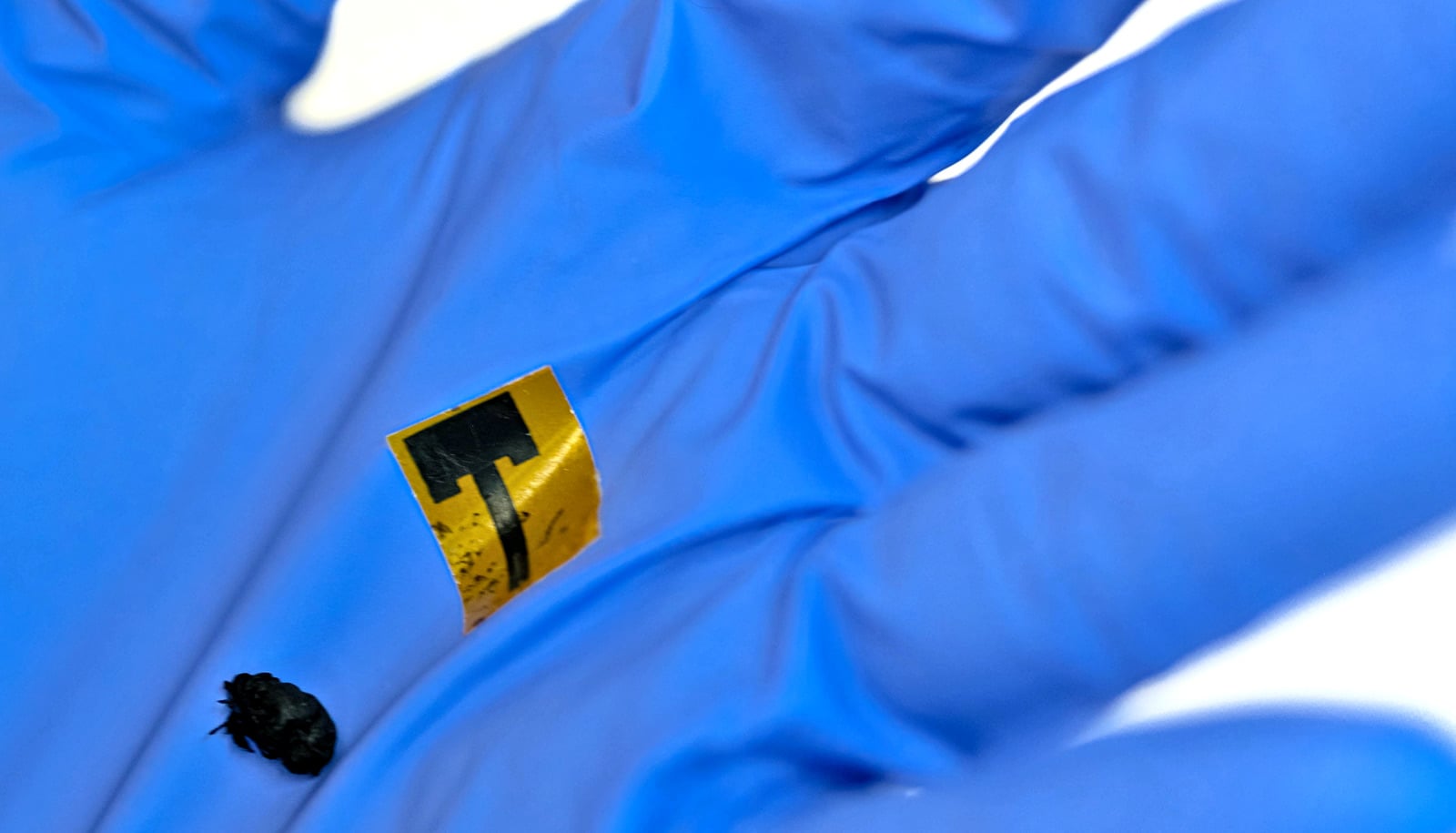

Carbon nanotubes are long, hollow carbon molecules, similar in shape to a garden hose but with sides just one atom thick and diameters about 50,000 times smaller than a human hair.

The outer walls of nanotubes are made of rolled graphene. And the wrapping angle of the graphene can vary, much like the angle of a roll of holiday gift wrap paper. If the gift wrap is rolled carefully, at zero angle, the ends of the paper will align with each side of the gift wrap tube. If the paper is wound carelessly, at an angle, the paper will overhang on one end of the tube.

The atomic structure and electronic behavior of each carbon nanotube is dictated by its wrapping angle, or chirality, and its diameter. The two traits are represented in a “(n,m)” numbering system that catalogs 466 varieties of nanotubes, each with a characteristic combination of chirality and diameter. Each (n,m) type of nanotube has a characteristic color.

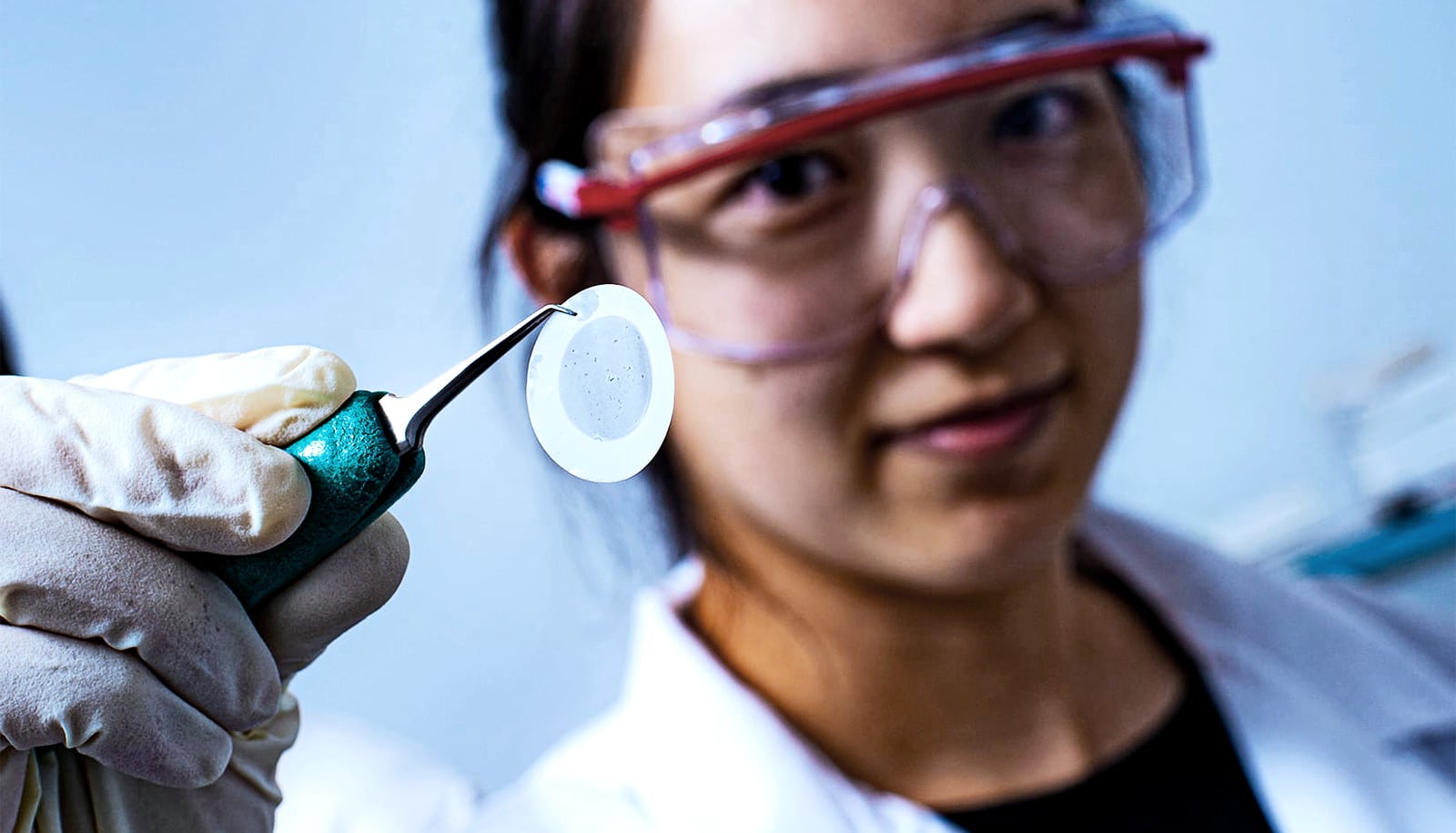

Kauppinen’s research group has studied carbon nanotubes and nanotube thin films for years, and it previously succeeded in mastering the fabrication of colored nanotube thin films that appeared green, brown, and silver-grey.

In the new study, Kauppinen’s team examined the relationship between the spectrum of absorbed light and the visual color of various thicknesses of dry nanotube films and developed a quantitative model that can unambiguously identify the coloration mechanism for nanotube films and predict the specific colors of films that combine tubes with different inherent colors and (n,m) designations.

Rice University engineer and physicist Junichiro Kono, whose lab solved the mystery of colorful armchair nanotubes in 2012, provided films made solely of (6,5) nanotubes that were used to calibrate and verify the new model. Then researchers used the model to calculate the absorption of the film and its visual color. Experiments showed that the measured color of the film corresponded quite closely to the color forecast by the model.

The new model shows that the thickness of a nanotube film, as well as the color of nanotubes it contains, affects the film’s absorption of light. The atlas of 466 colors of nanotube films comes from combining different tubes. The research showed that the thinnest and most colorful tubes affect visible light more than those with larger diameters and faded colors.

“Esko’s group did an excellent job in theoretically explaining the colors, quantitatively, which really differentiates this work from previous studies on nanotube fluorescence and coloration,” says Kono, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, physics and astronomy, and materials science and nanoengineering, as well the director of Rice’s Applied Physics Graduate Program.

Since 2013, Kono’s lab has pioneered a method for making highly ordered 2D nanotube films. Kono says he had hoped to supply Kauppinen’s team with highly ordered 2D crystalline films of nanotubes of a single chirality.

“That was the original idea, but unfortunately, we did not have appropriate single-chirality aligned films at that time,” Kono says. “In the future, our collaboration plans to extend this work to study polarization-dependent colors in highly ordered 2D crystalline films.”

The experimental method the researchers used to grow nanotubes for their films was the same as in their previous studies: Nanotubes grow from carbon monoxide gas and iron catalysts in a reactor that is heated to more than 850 degrees Celsius (1562 degrees Fahrenheit). The growth of nanotubes with different colors and (n,m) designations is regulated with the help of carbon dioxide that is added to the reactor.

“Since the previous study, we have pondered how we might explain the emergence of the colors of the nanotubes,” says Nan Wei, an assistant research professor at Peking University who previously worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Aalto. “Of the allotropes of carbon, graphite, and charcoal are black, and pure diamonds are colorless to the human eye. However, now we noticed that single-walled carbon nanotubes can take on any color: for example, red, blue, green, or brown.”

Kauppinen says colored thin films of nanotubes are pliable and ductile and could be useful in colored electronics structures and in solar cells.

“The color of a screen could be modified with the help of a tactile sensor in mobile phones, other touch screens or on top of window glass, for example,” he says.

Kauppinen says the research can also provide a foundation for new kinds of environmentally friendly dyes.

Additional study coauthors are from Rice, the University of Utah, Aalto University, Peking University, and Dalian Maritime University in China.

Funding for the research came from the European Union, Aalto University’s Energy Efficiency Research Program, the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation, and the Alberta Technical University of Munich International Graduate School for Hybrid Functional Materials.

Source: Rice University