A newly discovered species of clingfish has a set of teeth that could put a shark to shame.

Scientists discovered and named the new genus and species of clingfish after stumbling upon a specimen preserved in a jar dating back to the 1970s. The fish was unmistakably different from the other 160 known clingfishes, named for the disc on their bellies that offers massive sticking power in wet, slimy environments.

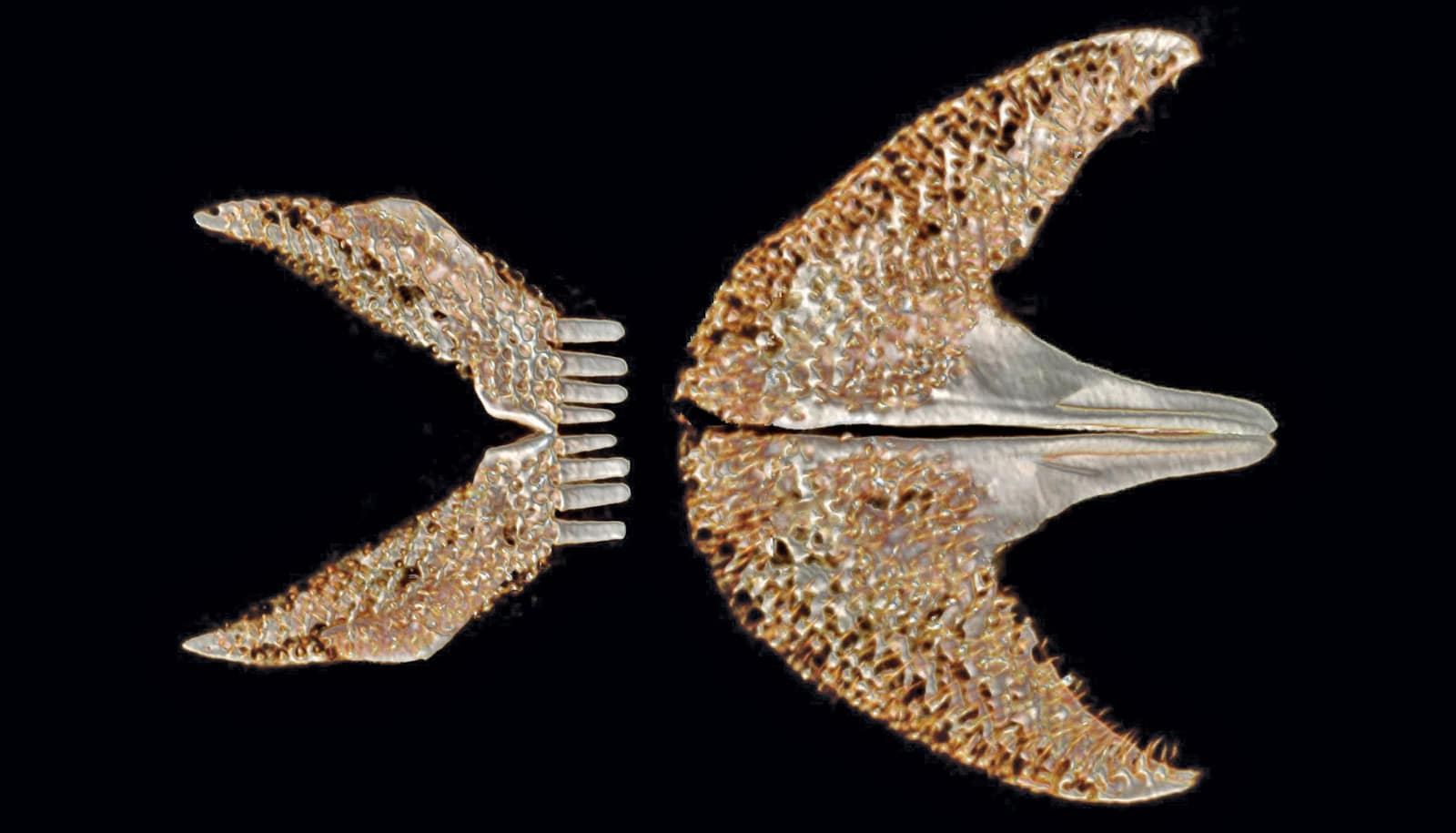

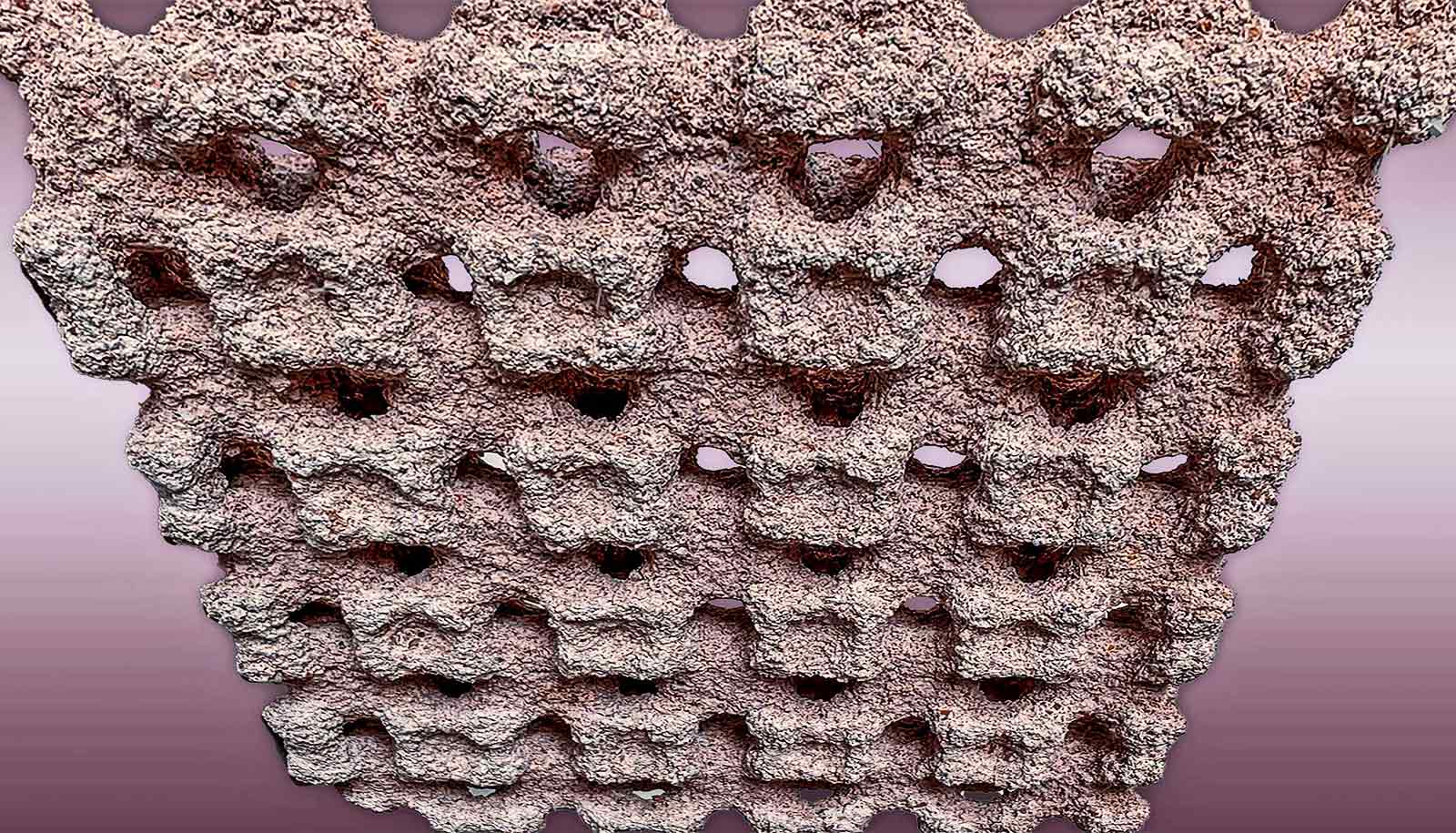

Researchers named the new species “duckbilled clingfish” (Nettorhamphos radula) for its broad, flat snout―not unlike the bill of a duck―that holds an impressive number of tiny, conical teeth.

“This fish has characteristics we just haven’t seen before in other clingfish. It’s the teeth that really gave away the fact that this is a new species,” says lead author Kevin Conway, a fish taxonomist and associate professor at Texas A&M University.

A detailed description of the new genus and species appears in the journal Copeia.

Scientists are interested in clingfish because of their ability to stick to rough surfaces. The finger-sized fish uses suction forces to hold up to 150 times its own body weight. Understanding the biomechanics of these fish could be useful in designing devices and instruments to be used in surgery, or to tag and track whales in the ocean.

Museum treasure

Conway and coauthor Glenn Moore of Western Australian Museum discovered the new clingfish while looking through specimens preserved in jars at the museum in Welshpool, Australia.

“A discovery like this highlights the importance of museum collections and reminds us just how much lies waiting to be uncovered.”

It’s common for unknown specimens collected during surveys to be registered and shelved until an expert has the time and interest to take a closer look.

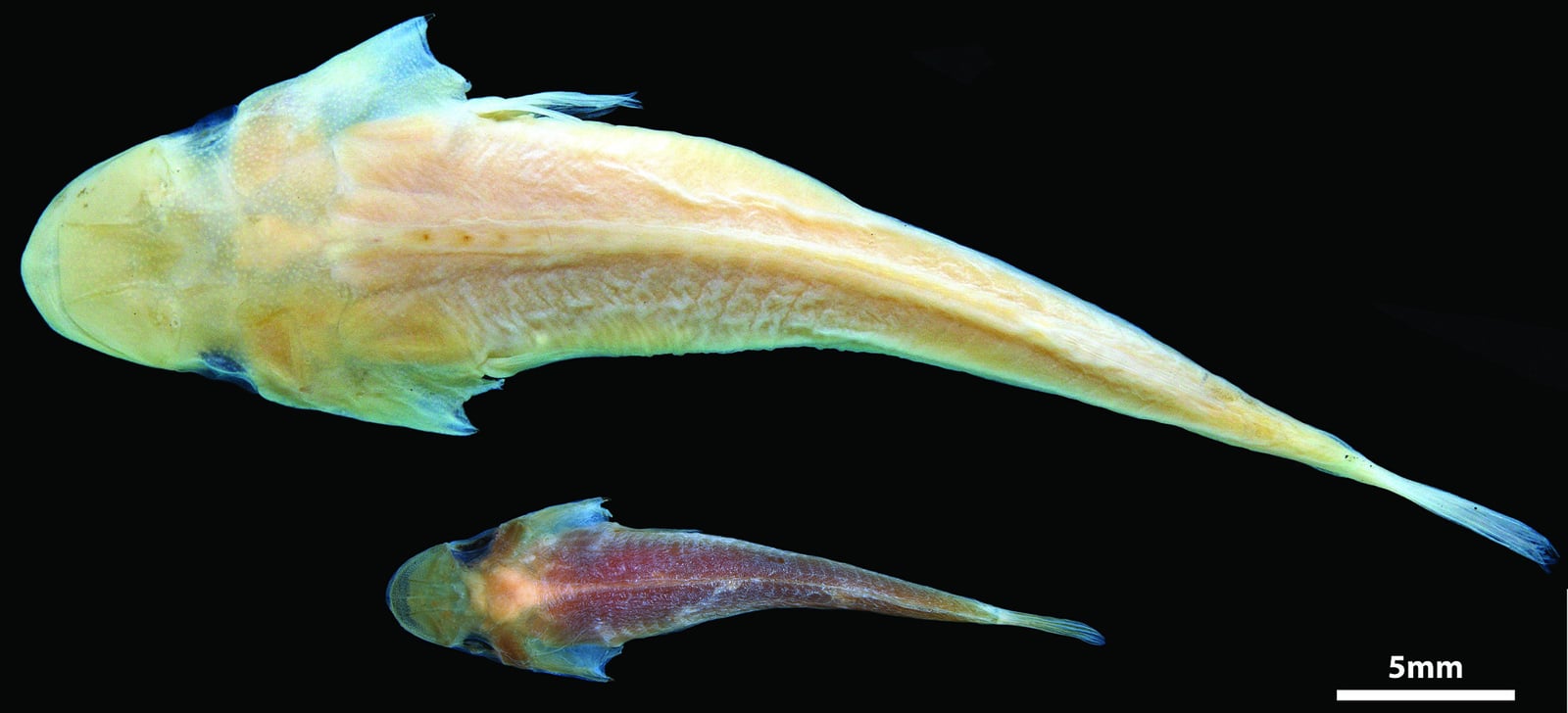

This specimen was caught off the coast of Southern Australia in 1977. Even though the fish is only as big as a pinky finger, its unique teeth structure caught their attention. A couple of hours later, Moore found yet another specimen with similar features on the museum shelves. Together, the specimens are thought to be the only two of this new species that exist out of water.

“A discovery like this highlights the importance of museum collections and reminds us just how much lies waiting to be uncovered,” Moore says. “Finding a previously unknown specimen in a jar is exciting, but our collections of identified specimens are equally important so that we have something to compare against.”

Too rare to dissect

The researchers suspected they had discovered a new species that represented a new genus of clingfish, given the unusual mouth structure and teeth arrangement, but they faced a conundrum: Naming a new species requires an intact, complete fish with good documentation of its morphology and clear distinctions from other species. With only two known specimens, dissection was out of the question.

Instead they turned to Adam Summers of the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories,, who studies clingfish and is actively working to scan and digitize every fish species in the world using a computerized tomography (CT) scanner. Each completed scan is housed on Open Science Framework.

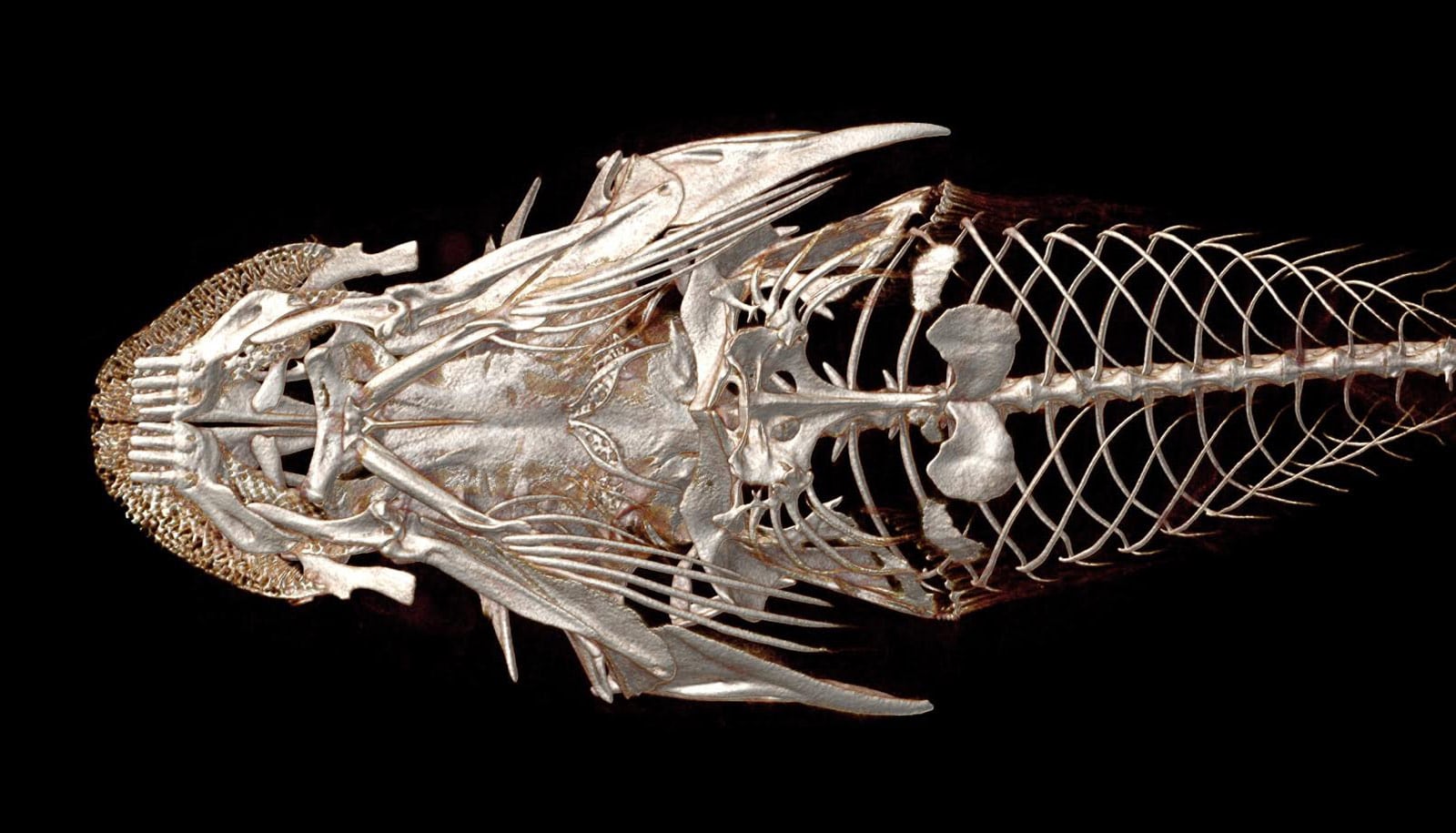

Using the scanner, scientists captured even finer details of the new clingfish than would be possible through manual dissection. They also used the digital scans to 3D print parts of the fish in larger-than-life size to be able to analyze the mouth and jaw structures.

“This CT scan allowed us to take a completely noninvasive look at the entire skeleton of the fish, and it produced a gorgeous set of morphological photos that you couldn’t get from dissection,” Summers says. “It’s a testament to the importance of using these noninvasive methods of data collection.”

These clingfish are venomous and nobody knew it

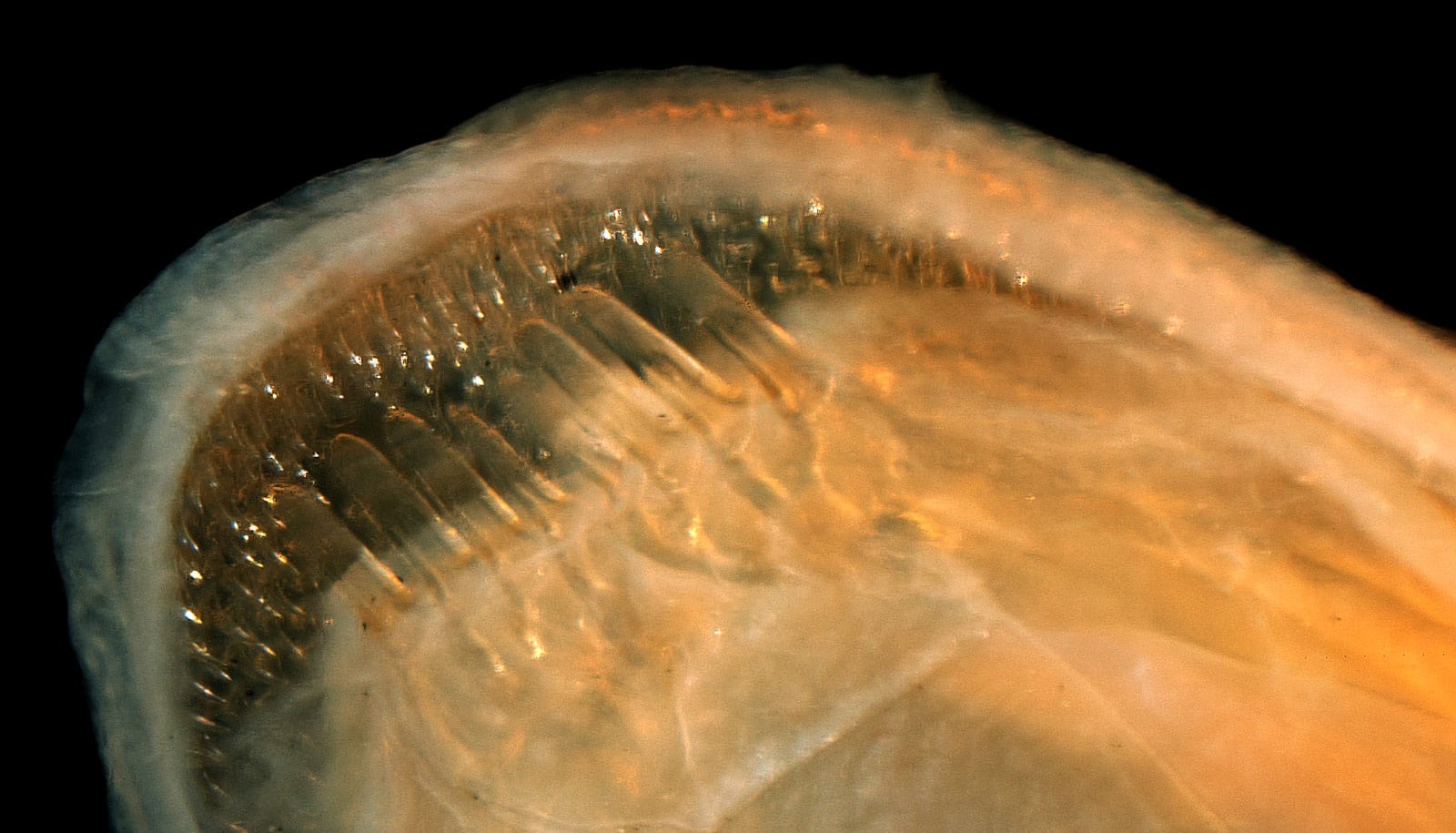

The scans allowed the researchers to hone in on the fish’s skeletal structure from many different angles and essentially digitally dissect parts of the fish. They estimate the tiny fish has between 1,800 to 2,300 individual teeth—or 10 times what all other known clingfish have. The teeth point backward, which would suggest a gripping function, Conway says, but the researchers can’t be sure since the fish has never been observed in the wild.

The duckbilled clingfish joins the ranks of hundreds of new fish species that are described each year. It’s more unusual for these new species to be placed into a new genus―in this case, the fish’s wider and longer upper jaw and abundance of tiny, dagger-like conical teeth were the sure signs of a brand-new genus.

The researchers are particularly pleased to have discovered a new clingfish in a region of Southern Australia that is known for its clingfish diversity and abundance.

“I think it’s remarkable that we would add to this diversity with yet another new genus,” Conway says. “It’s pretty special given this fauna is already pretty well studied.”

The National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: University of Washington