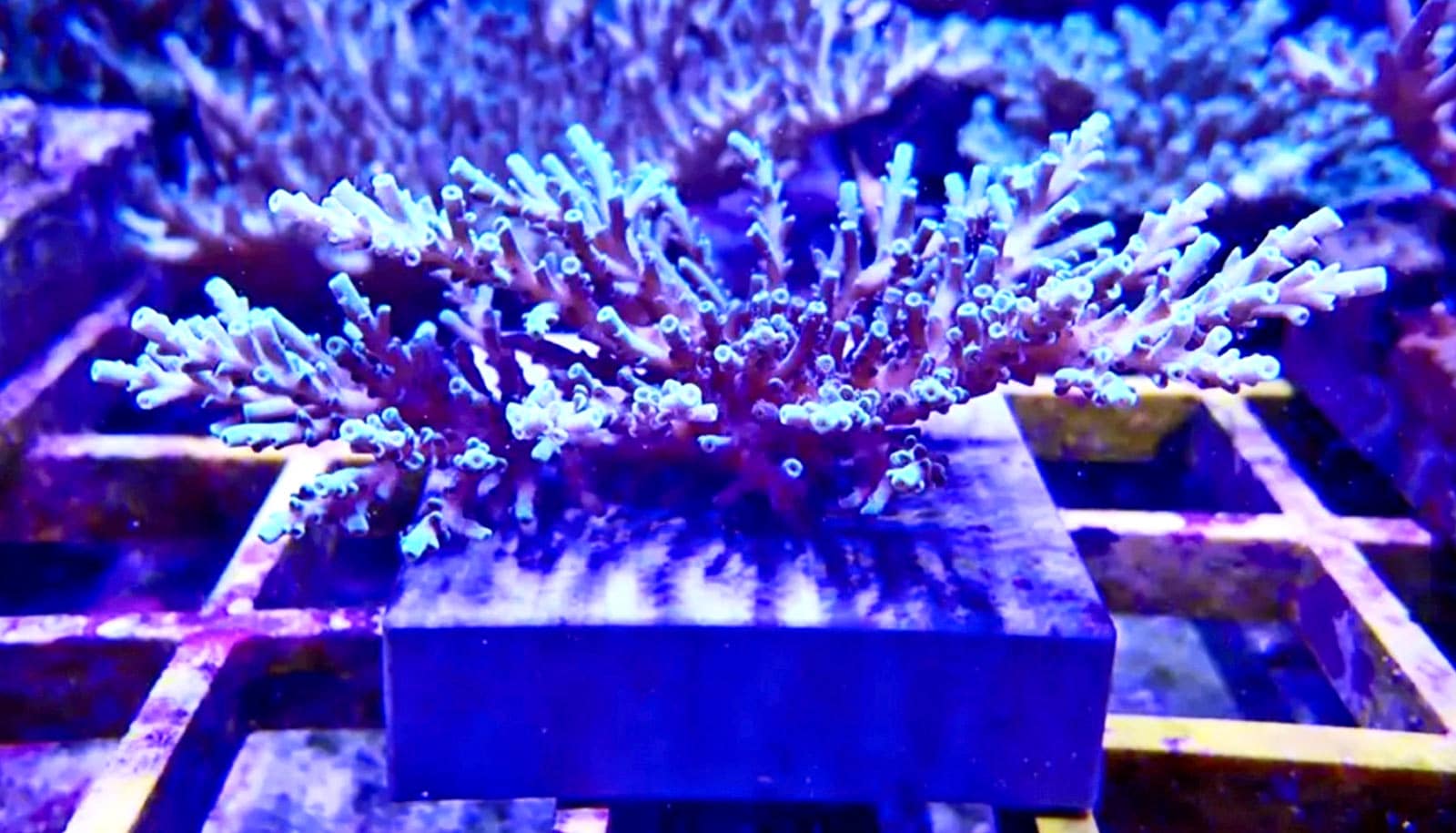

Global warming has caused twice as many ocean-dwelling species as land-dwelling species to disappear from their habitats, researchers report.

The greater vulnerability of sea creatures may significantly impact human communities that rely on fish and shellfish for food and economic activity, according to the new study.

It’s the first to compare cold-blooded marine and land species’ sensitivity to warming and their ability to find refuge from the heat while staying in their normal habitats. The authors combed through worldwide research on nearly 400 species from lizards and fish to spiders. They calculated safe conditions for 88 marine and 294 land species as well as the coolest temperatures available to each species during the hottest parts of the year.

“We find that, globally, marine species are being eliminated from their habitats by warming temperatures twice as often as land species,” says lead author Malin Pinsky, an associate professor in the department of ecology, evolution, and natural resources at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

“The findings suggest that new conservation efforts will be needed if the ocean is going to continue supporting human well-being, nutrition and economic activity.”

The researchers found that marine species are, on average, more likely to live on the edge of dangerously high temperatures. Additionally, many land animals can hide from the heat in forests, shaded areas, or underground, a luxury not open to many sea animals.

The loss of a population can deplete the species’ genetic diversity, have cascading impacts on their predators and prey, and alter ecosystems that benefit human society.

The study notes that ancient extinctions have often been concentrated at specific latitudes and in specific ecosystems when the climate changed rapidly. Future warming is likely to trigger the loss of more marine species from local habitats and more species turnover in the ocean.

“Understanding which species and ecosystems will be most severely affected by warming as climate change advances is important for guiding conservation and management,” the study says.

The study appears in the journal Nature. Additional researchers from Rutgers; McGill University; University of California, Santa Barbara; Stanford University; and the University of Oslo contributed to the study.

Source: Rutgers University