Human-caused climate change made the record rainfall that fell over Houston during Hurricane Harvey roughly 3 times more likely and 15 percent more intense, researchers report.

“The takeaway from this paper is that Harvey was more intense because of today’s climate, and storms like Harvey are more likely in today’s climate,” says study coauthor Antonia Sebastian, a postdoctoral research associate with the Severe Storm Prediction, Education, and Evacuation from Disasters (SSPEED) Center at Rice University.

“It highlights the need to consider that our hazards are changing over time, and that we should be considering those changes in the design of our infrastructure,” Sebastian says.

Sebastian has spent a decade studying urban flooding and flood risks in Houston, first as a doctoral student and later as a research associate at SSPEED. She was completing a one-year visiting appointment at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands when Harvey struck Houston, and she was asked to participate in the World Weather Attribution study by lead author Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, senior researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), and Maarten van Aalst, director of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre.

“This multimethod analysis, drawing upon both observed rainfall data and high-resolution climate models, confirms that heavy rainfall events are increasing substantially across the Gulf Coast region because of human interference with our climate system,” says Van Oldenborgh.

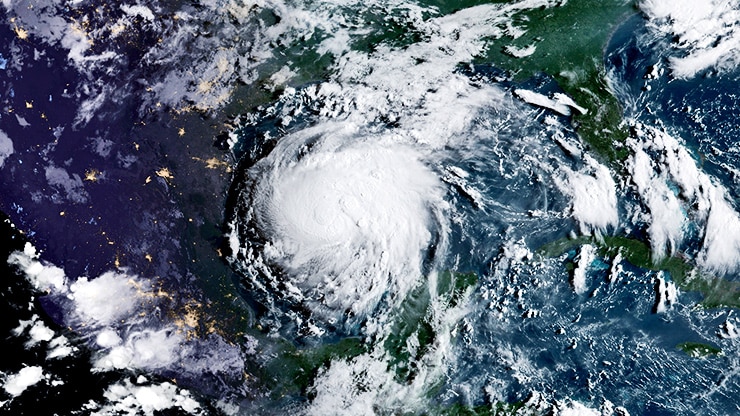

Harvey made landfall August 25 near Corpus Christi, Texas, as a Category 4 hurricane and stalled. As a tropical storm, it dropped more than 30 inches of rain on Southeast Texas and caused record catastrophic flooding in Houston and the surrounding region. In east Harris County, a record 51.89 inches of rain—the highest storm total in US history—was recorded over the six-day period from August 25 to 30. During the first three days of the storm, 41.07 inches fell over Baytown.

For a specific location like Houston, the study found that the maximum observed rainfall is still extremely rare in today’s climate—less than a one-in-9,000-year event. However, the chances of seeing this much rain over a three-day period anywhere over the entire Gulf Coast region are much higher, but still small—less than once every 100 years.

“These results make a clear case for why climate change information should be incorporated into any plans for future improvements to Houston’s flood infrastructure,” Sebastian says. “The past is no longer an accurate predictor of present or future flood-related risks.”

Due to global warming, global temperatures in today’s climate are about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit higher than pre-industrial temperatures, the researchers say. They estimate that even if Earth met the global targets set by the Paris Agreement of limiting warming to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, an event like Harvey will see a further increase of about a factor of three in probability.

“But if we miss those targets, the increase in frequency and intensity could be much higher,” says study coauthor Karin van der Wiel, a postdoctoral researcher at KNMI.

How to know if climate change caused the weather

“Although the rainfall levels from Harvey are extremely rare, additional factors, such as rapid population growth, urban growth policies, and aging water-management infrastructure, further exacerbated the ultimate impacts of this storm,” van Aalst says.

“Damage from storms like Harvey, Ike in 2008, and the Tax Day Flood of 2016 illustrate the importance of managing exposure and vulnerability when reducing the level of flood impacts in Houston.”

The researchers report their findings in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The MacArthur Foundation funded the research. Sebastian’s coauthors included Dutch researchers from both KNMI and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre in The Hague, Netherlands, and English and US researchers from the University of Oxford, Princeton University, and Princeton-based Climate Central.

The team is part of World Weather Attribution, an international effort to analyze and communicate the possible influence of climate change on extreme weather events, such as extreme rainfall, heat waves, and droughts. SSPEED is not affiliated with World Weather Attribution.

Source: Rice University