Chronic, debilitating pain hits people with fewer financial resources the hardest, new research suggests.

A large number of Americans live with chronic pain, which can limit their quality of life and leads some to seek relief from potentially dangerous opioid medications.

Nearly 10 percent of Americans over age 50 suffer from high-impact, long-standing pain that has a substantial negative effect on work, social, or other everyday activities.

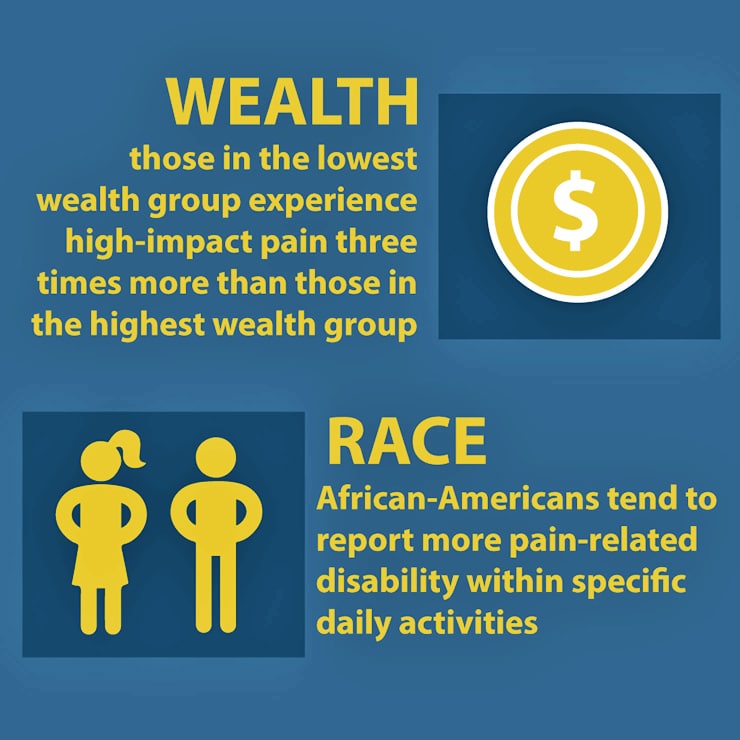

Yet, those whose household wealth is in the lowest quartile experience high-impact pain three times more than those in the highest wealth group, says Mary Janevic, a faculty member of the Center for Managing Chronic Disease and assistant research scientist in the health behavior and health education department at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

“While pain affects all sectors of society, wealthier people tend to have better health, less psychological stress, occupations that are less likely to cause injury, better access to medical care, and the ability to pay for ‘extras’ like gym memberships or complementary treatments that help some people manage pain,” says Janevic. “They also can pay for conveniences like more accessible homes that enable them to function better even when they are experiencing pain.”

“We need to expand access among vulnerable groups to evidence-based nonpharmacological treatments…”

The study, based on a large nationally representative sample of midlife and older Americans, also found that African-Americans, as well as people with less education and wealth, tend to report more pain-related disability within specific categories of daily activities and were more likely to experience financial problems due to pain.

“In addition to accumulating less wealth due to a long history of discrimination and housing segregation, other research has shown that African-Americans tend to be undertreated for pain. These factors could contribute to the observed racial disparities in pain disability,” Janevic says.

Out of a group of nearly 1,800 respondents who were asked in detail about their pain, the researchers found that 778 had pain in the last year lasting at least one week and 176 of those had prolonged episodes, defined as seven months or longer, with substantial adverse effects on daily life.

In America, less education often means more chronic pain

The health conditions most strongly associated with high-impact pain were arthritis and depression.

“Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in chronic pain, like all health disparities, will not go away until we have a more equitable, less discriminatory society with universal access to effective treatments,” Janevic says. “Pursuing policies that advance this vision is probably the most important thing we can do.”

In the meantime, Janevic says the health care system should work to make interdisciplinary pain treatment accessible and affordable to all older adults.

“We need to expand access among vulnerable groups to evidence-based nonpharmacological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and chronic pain self-management programs that can help reduce pain’s effect on daily functioning,” she says.

Are older adults more prone to chronic pain?

The researchers’ work is outlined in an article appearing in the Journal of Pain.

Additional coauthors of the study are from Miami University, the Yale University School of Medicine, and the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

The National Institute on Aging supported this work in part. The National Institutes of Health also provided support.

Source: University of Michigan