Using a chip to process blood samples, doctors can monitor the amount of lung cancer cells in a patient’s blood to determine if a treatment is working by the fourth week, a new study shows.

Such data could allow clinicians to adapt cancer treatments to patients’ needs and improve treatment outcomes.

“Currently, there’s typically a wait of weeks to months before we can fully assess the effectiveness of cancer treatment,” says Shruti Jolly, professor of radiation oncology, associate chair of community practices at the University of Michigan and co-corresponding author of the study.

“However, with this chip, we may be able to sidestep prolonged, ineffective therapy and quickly pivot to alternatives, thus saving patients from needless side effects. This technique has the potential to shift cancer diagnostics, moving from a delayed single assessment to a more continuous surveillance and facilitating the delivery of personalized cancer treatment.”

More sensitive cancer markers

Today, clinicians use CT scans to see if a tumor shrank or grew, but only large changes in size are easily noticed. Tumor biopsies provide more exact information, but they can’t be done frequently enough to get regular updates.

That’s why many clinicians are turning to liquid biopsies, or tests that look for signs of cancer in the patient’s blood, such as cancer cells that tumors have shed. Blood samples can be collected frequently, but they are only useful if the cells are present in high enough levels for biomedical instruments to detect.

Lung cancer is a particular problem. Other FDA-approved tools for detecting cancer cells in blood samples have proven ineffective for monitoring lung cancer treatments—likely because they targeted a single protein on the cells’ surfaces that is less common in lung cancers, the researchers say.

“We were looking for more sensitive markers of cancer that we could use to closely monitor treatments,” says corresponding author Sunitha Nagrath, professor of chemical and biomedical engineering.

“In some cases, only about half of cancer patients respond to the treatments, leaving the rest with poor outcomes. Treatments may also be expensive and cause adverse reactions in some patients, so it’s important for clinicians to know early on whether a treatment is going to be effective—or whether they may be better off with a different treatment.”

How the ‘GO chip’ works

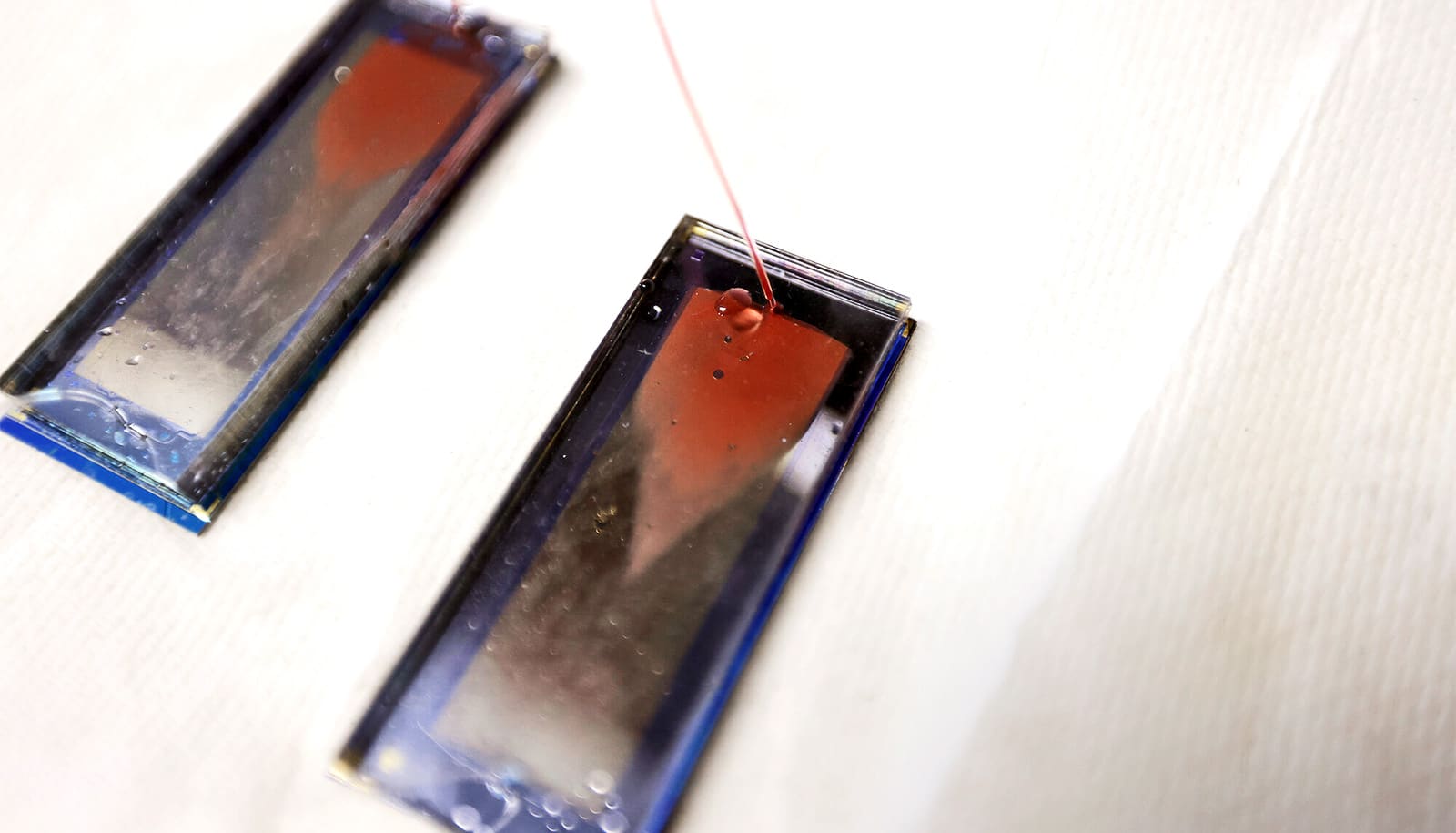

The “GO chip” developed by Nagrath’s team, first demonstrated in 2013, succeeded where others fell short. It traps cancer cells like a piece of flypaper traps flies. But unlike flypaper, the chip only catches its target. Antibodies mounted on microscopically thin sheets of graphene oxide in the chip—which give the device its name—recognize a wide array of cancer-specific protein markers found on the surfaces of cancer cells.

As the blood is pushed through channels in the chip, the antibodies trap cells, eventually concentrating enough to work with. With the cells locked in place, the researchers can not only count them but confirm that they are indeed cancerous and determine how the cells’ biochemistry varies between patients and treatment stages.

To test that the GO chip could monitor lung cancer treatments, the researchers used it to collect cancer cells from the blood of 26 patients receiving both chemotherapy and immunotherapy for stage 3 lung cancer. The researchers took samples before cancer treatment and after the patients’ first, fourth, 10th, 18th, and 30th weeks of treatment.

Their experiment revealed that when the number of cancer cells in a patient’s blood doesn’t decrease by at least 75% by the fourth week of treatment, their cancer is more likely to persist after treatment.

The study also shows that cancer cells collected from patients whose cancer did not respond to treatment had activated genes that may have made the cancer resilient. These genes might be good targets for future cancer therapies, but further study is required to test this idea.

The study appears in the journal Cell Reports.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The GO chips were built in the Lurie Nanofabrication Facility. Jolly is also the chief clinical strategy officer for cancer services at Michigan Medicine. Nagrath is also a co-director of Liquid Biopsy Shared Resources for the University of Michigan’s Rogel Cancer Center.

Source: Derek Smith for University of Michigan