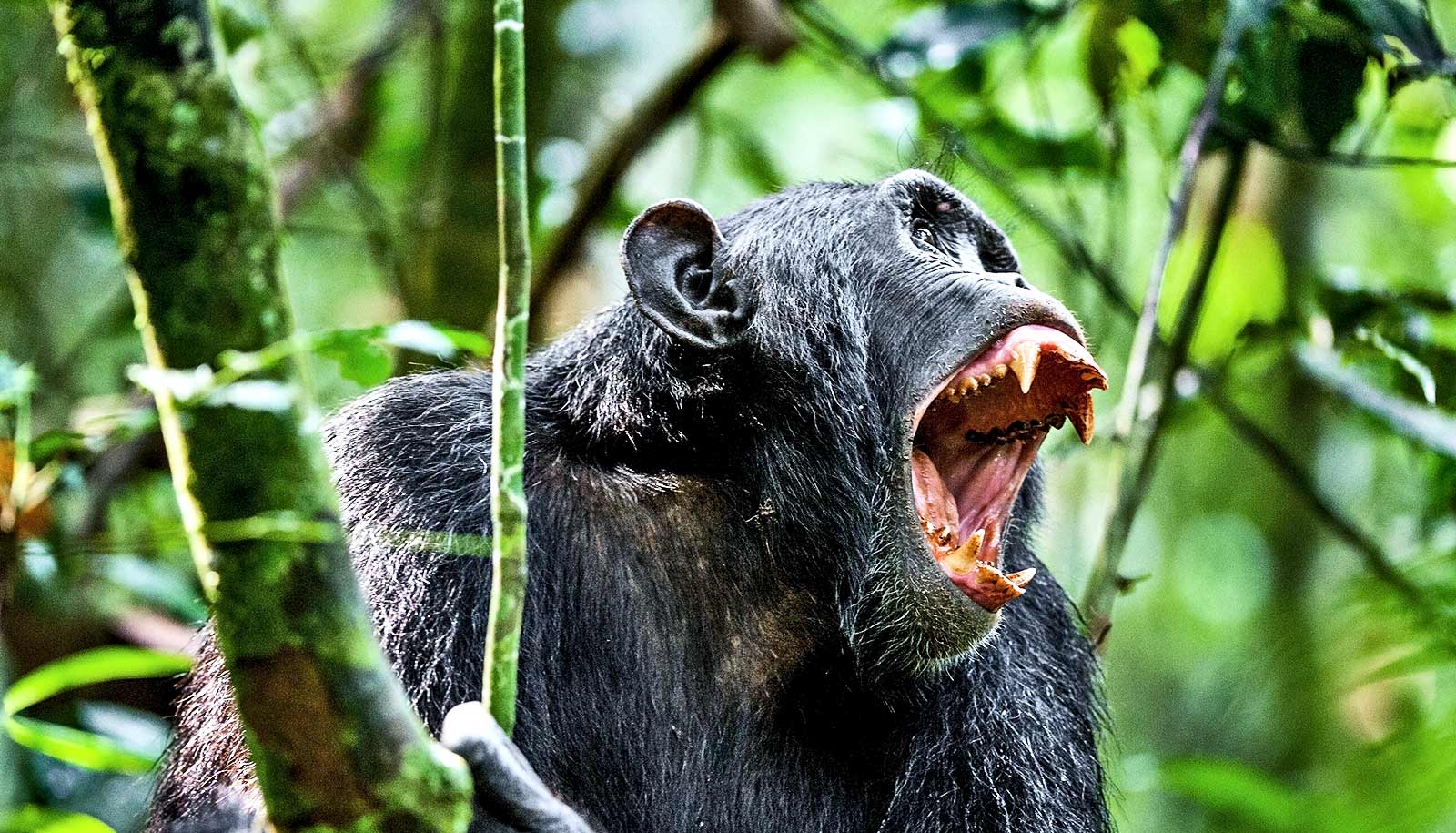

Power. Ambition. Jealousy. The same things that fuel deadly clashes in humans can also tear apart chimpanzees, our closest animal relatives, according to a new study.

In the early 1970s, primatologist Jane Goodall and colleagues studying chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania, watched as a once-unified chimp community disintegrated into two rival factions. What followed was a period of killings and land grabs, the only civil war ever observed in wild chimpanzees.

Now, scientists have been able to take a closer look at the seeds of the conflict thanks to newly digitized field notes in the Jane Goodall Institute Research Center at Duke University. What started as infighting among a few top males vying for status and mates is likely what eventually caused the whole group to splinter.

The exact nature and cause of the split leading to what Goodall called the “Four-Year War” at Gombe from 1974 to 1978 has long been a mystery, says first author Joseph Feldblum, postdoctoral associate with professor Anne Pusey.

Friction among friends

During the war, males within an area of the park known as Kasekela teamed up to raid neighboring territories, brutally beating and killing half a dozen former comrades.

Some researchers have suggested the friction was sparked by the banana feeding station Goodall used to lure chimpanzees for observation. They proposed that two distinct chimp communities may have existed all along or were already dissolving when Goodall began her research, and the feeding station merely brought them together in a temporary truce until they parted again.

But findings from the new study suggest something more was going on.

Using data they extracted from Goodall’s copious hand-written notes and check sheets, which Pusey has spent the last 25 years archiving and digitizing, the researchers analyzed the shifting alliances among 19 male chimpanzees leading up to the split.

“Understanding why cohesion breaks down can give you clues about the forces that bind social groups together in the first place.”

They mapped the chimps’ social networks at different periods between 1967 and 1972 to pinpoint when relations began to fray. They considered two males to be buddies if they were spotted arriving together at the feeding station more often than other pairs.

Next, the researchers identified the most tightly knit groups in each network and determined how much their members changed over time.

“We used network analysis to quantify the degree to which individuals are cliquish, essentially,” Feldblum says.

Their analyses suggest that for the first few years, from 1967 to 1970, males in the original group intermingled.

But statistical tests revealed clusters of males that grew more distinct over time. Some males spent more time in the northern part of the range. Another group increasingly withdrew to the south.

By 1971, the northern and southern males met less and less often. When they did encounter each other, they would hurl branches, hoot, and charge through the forest as a show of strength.

“We would hear these pant-hoot calls from the south and say to ourselves: the southern males are coming! All the northern ones would go up trees, and there’d be a lot of screaming and displaying,” says Pusey, who observed them firsthand as a doctoral student at Gombe from 1970 to 1975.

Struggle for dominance

Within a year, the cliques began to harden and became increasingly exclusive, results show.

Where once the chimps groomed and spent time with other males both inside and outside their subgroup, by 1972 they socialized almost exclusively with males on the inside, with minimal range overlap between northern and southern males.

Given the timing, a power struggle between three high-ranking males likely triggered the schism, the researchers say. The community’s troubles came amid rising tensions between a recently crowned alpha male, Humphrey, and his southern rivals Charlie and Hugh.

“Humphrey was large and he was known to throw rocks, which was scary,” Pusey says. “He was able to intimidate Charlie and Hugh separately, but when they were together he tended to keep out of the way.”

competition for reproductively cycling females, whose availability was unusually low, likely exacerbated their dominance struggle. The resulting hostility was not restricted to these rival males; it affected the whole web of social ties the males were embedded within.

“It’s not possible to say for sure that any one thing was causal, since this is the only such event we’ve ever seen in chimpanzees,” Feldblum says. But the results mirror what researchers have documented in other primates, including humans.

Germy friends may keep social chimps healthy

A previous analysis of schisms in nearly 50 human societies worldwide found that internal political conflict frequently foreshadows a split in human groups as well, followed closely by competition for scarce resources.

Collectively, the findings suggest that such social dynamics are deeply rooted in the primate evolutionary tree.

“Understanding why cohesion breaks down can give you clues about the forces that bind social groups together in the first place,” Feldblum says.

Like people, chimps prefer teamwork over competition

The study appears in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

Other authors are from Duke and from Arizona State University. The Jane Goodall Institute, and grants from the National Science Foundation, the Harris Steel Group, the Windibrow Foundation, the Leakey Foundation, the University of Minnesota, and Duke funded the work.

Source: Duke University