Chemical aversion therapy may be effective in curbing alcohol abuse among heavy drinkers, a new small scale study indicates.

Researchers employed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine how chemical aversion therapy affects brain activity related to craving.

“Among organizations that treat alcohol abuse, there is growing awareness of the importance of craving,” says Ralph Elkins, the director of research at the Schick Shadel Hospital. “Craving was recently added as one of the defining criteria for diagnosing alcohol use disorder in the DSM-5,” health care providers’ authoritative manual for diagnosing mental conditions.

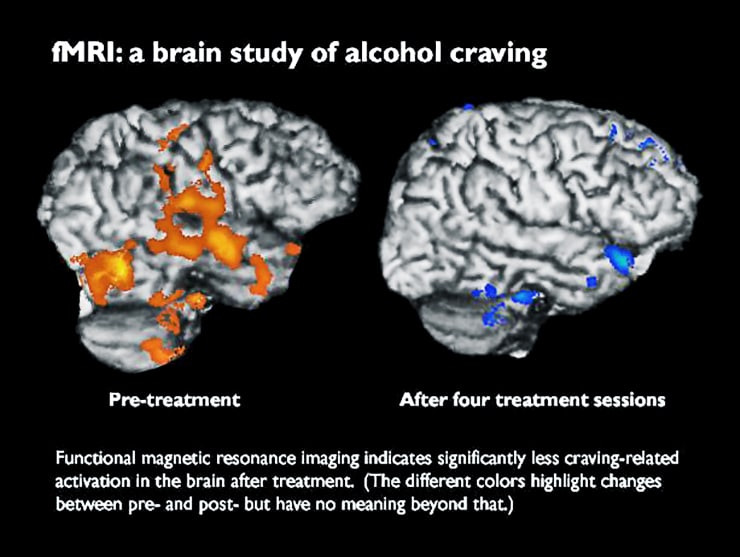

fMRI scans taken before and during 10 days of Schick’s in-house treatment showed significant changes in brain activity among the 13 study subjects.

“This implicates craving reduction as a mechanism of how chemical aversion therapy is changing patients’ drinking behavior,” says Hunter Hoffman, a radiology research scientist for University of Washington Medicine and investigator in mechanical engineering at the University of Washington’s Human Photonics Lab. “Further fMRI brain studies could explore chemical aversion therapy’s value with opioid dependence and other substance abuse.”

“The brain does not lie…and our scans confirmed what the patients were reporting about less feelings of craving.”

People with alcohol-use disorder experience pleasure and a sense of reward when they drink, and learn to associate alcohol with various people and situations. The brain encourages the repetition of this behavior.

“When someone tries to quit drinking alcohol, he may see others enjoying alcohol in those familiar circumstances, which activates his brain’s pleasure center and can lead him to fantasize about drinking again. That can cause a sober person to crave alcohol,” Elkins says.

Fortunately, the human brain also has evolved mechanisms of repulsion and aversion to actions that lead to feelings of physical illness; for example, people quickly learn to avoid poisonous foods and other foods that make them nauseated.

Schick’s treatment is designed to reduce craving by activating these aversion mechanisms in the brain. It trains patients to associate alcohol consumption with nausea and vomiting.

More than 900 genes linked to alcoholism in rats

Before the treatment began, the 13 study participants had self-reported alcohol abuse lasting 18 years, on average. One year after in-house treatment ended, nine of the 13 reported that they had successfully abstained from alcohol and that it still repulsed them.

Functional MRI detects brain activity—changes in blood oxygen levels, specifically. Each study subject underwent two fMRI scans: before treatment began and after the fourth (of five) treatment sessions at Schick Shadel. Each subject also answered survey questions about their senses of craving before, during, and after treatment.

Neuroimaging scientist Todd Richards administered the scans, instructing each patient to imagine two scenarios: one with a bottle of their favorite alcohol and one in their favorite non-alcohol setting. Richards alternated those cues every 30 seconds, yielding a composite image of activity to represent alcohol craving.

“The brain does not lie,” Richards says. “The activation pattern tells whether someone is craving, and our scans confirmed what the patients were reporting about less feelings of craving.”

Changes between the pre- and post-treatment scans show “significant reductions in craving-related brain activity in the occipital cortex,” a region of the brain previously associated with alcohol craving, Richards says.

The data, Hoffman says, suggest that chemical-aversion treatment is effective for alcohol-use disorder, but the study’s small scale and the lack of a control group underscore that more research is needed.

How alcohol during pregnancy ups baby’s addiction risk

The researchers report their findings in the journal Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

Source: University of Washington