The discovery in 2019 of a lone small female tortoise living on one of the most inaccessible islands of the Galápagos Islands has baffled evolutionary biologists.

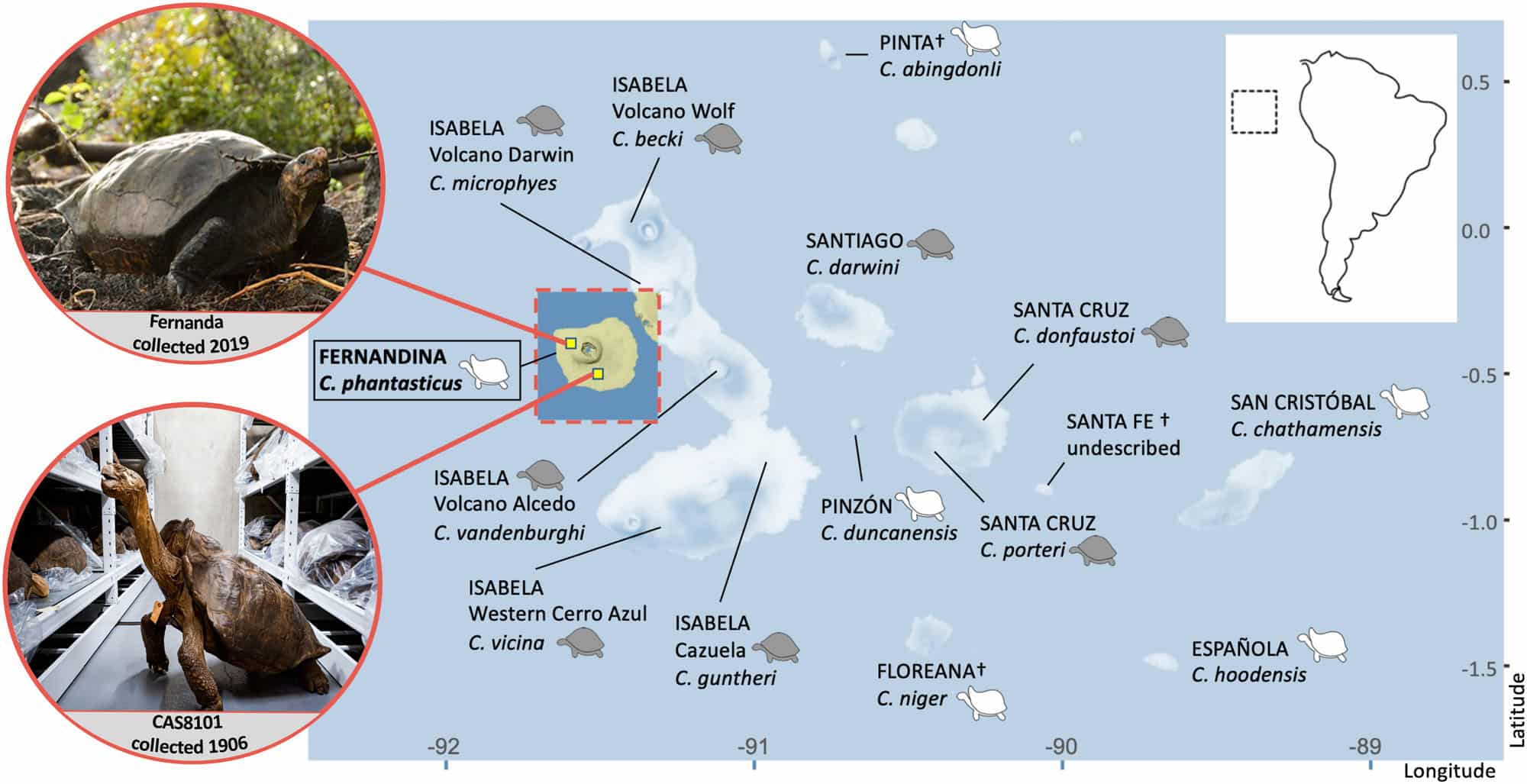

Only one other tortoise, a large male discovered in 1906, has ever been found on Fernandina Island, an isolated island on the western edge of the iconic archipelago.

A comparison of the genomes of Fernanda (as researchers call the recently discovered 50-year-old tortoise) and the 20th century male specimen now housed at the California Academy of Sciences, reveal that the two animals are closely related, doubling the number of known members of Chelonoidis phantasticus, researchers report in the journal Communications Biology.

But the discovery has raised many more questions.

“Vast amounts of the genomes are similar between the two animals, but the process that explains how this happened we just don’t know,” says Adalgisa Caccone, a senior research scientist and lecturer in Yale University’s department of ecology and evolutionary biology and senior author of the study. “This also shows the importance of using museum collections to understand the past.”

Giant tortoises of the Galápagos

It is believed that there are 15 distinct species of giant tortoise on the Galápagos Islands, according to Galápagos Conservancy, a nonprofit based in the United States.

The new finding clearly shows that the two tortoises found on Fernandina Island belong to their own lineage and are closer in relation to each other than to any other species of Galápagos tortoises, the numbers of which have been reduced by 85% to 90% since the early 19th century, largely due to the arrival of whalers and pirates who killed them for food.

“The finding of one alive specimen gives hope and also opens up new questions as many mysteries still remain,” says Caccone. “Are there more tortoises on Fernandina that can be brought back into captivity to start a breeding program? How did tortoises colonize Fernandina and what is their evolutionary relationship to the other giant Galápagos tortoises?”

The tortoises of Fernandina Island were believed to have been driven to extinction by volcanic eruptions on the island, including approximately 25 in the last two centuries. Areas of vegetation, scientists have theorized, were reduced by lava flows.

The Galápagos National Park and the Galápagos Conservancy plan to scour the island of Fernandina for relatives of Fernanda in hopes of preserving the species. The presence of additional tortoise scats and tracks suggests they may find more animals on the island, Caccone says. If more tortoises are found, she says, conservationists could start a captive breeding program.

Is Fernanda a hybrid?

Deciphering the evolutionary relationship between the two Fernandina tortoises might be trickier. For one thing, they look very different. The male specimen has a large and protruding carapace characteristic of saddleback tortoises, while Fernanda has a smaller, smoother shell. Caccone thinks that this shape difference is possibly due to stunted growth as a result of limited food options.

And while the genomes of the two animals are very similar, researchers discovered differences within the mitochondria, the energy-producing portion of cells that are passed down maternally. Since mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother, Caccone says it is possible that Fernanda is a hybrid, the progeny of a Chelonoidis phantasticus male and a C. nigra female, a now extinct species from the island of Floreana, the larger neighbor of Fernandina.

Humans moved different tortoise species, such as C. nigra, among the Galápagos islands—including to Isabela island, where many hybrids between the endemic species C. becki and the extinct C. nigra have been found. It is possible that a C. nigra female similarly found its way to Fernandina and mated with a male from C. phantasticus, leaving its mitochondrial DNA to all her descendants.

Caccone thinks that the male now housed in the California museum is probably a true representative of the original species. But to solve this new puzzle, she says, more tortoises from Fernandina need to be found.

Evolutionary biologists will work on these and other questions in coming years.

“These tortoises are the largest cold-blooded terrestrial herbivore on Earth and have a very important ecological role,” Caccone says. “So protecting them is important not only because of their iconic status but also because they are an important agent of ecosystem stability in the Galápagos.

“There is still a lot we don’t know, and what we learn will provide guidance to help protect them and with them the fragile and unique place on Earth they call home.”

Coauthors of the paper are from Newcastle University and Princeton University.

Source: Yale University