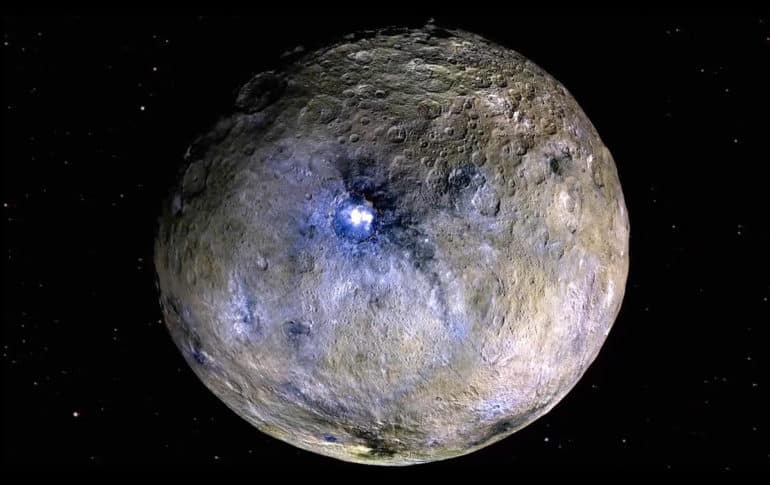

Scientists are puzzled by the solitary existence of an ice volcano on the dwarf planet Ceres.

“Imagine if there was just one volcano on all of Earth,” says Michael Sori of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. “That would be puzzling.”

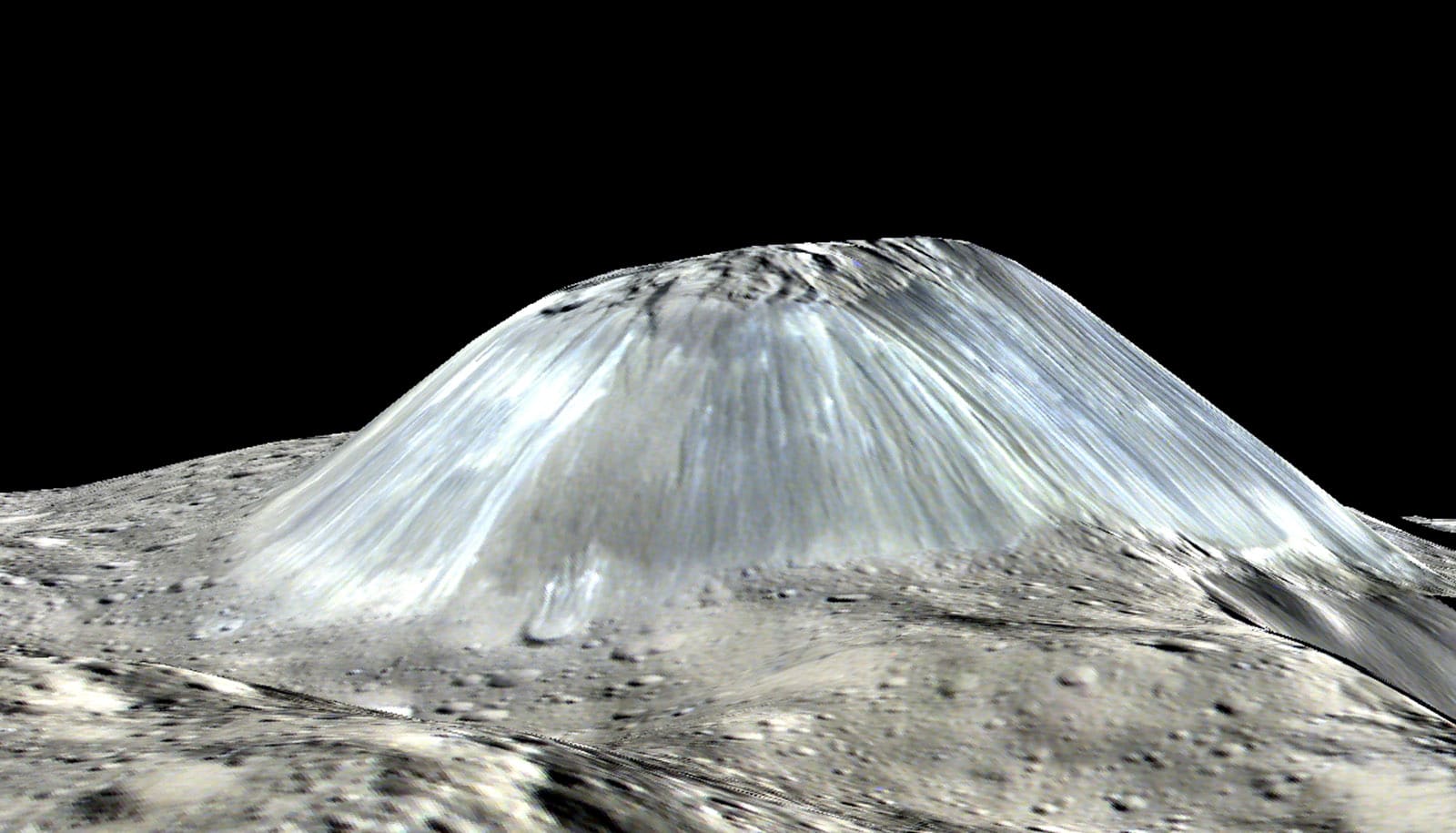

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft discovered the 4-kilometer-tall (2.5-mile) Ahuna Mons cryovolcano in 2015. Other icy worlds in our solar system, such as Pluto, Europa, Triton, Charon, and Titan, also may have cryovolcanoes, but Ahuna Mons is conspicuously alone on Ceres.

The dwarf planet, with an orbit between Mars and Jupiter, also lies far closer to the sun than other planetary bodies where cryovolcanoes have been found.

Now scientists show there may have been cryovolcanoes other than Ahuna Mons on Ceres millions or billions of years ago, but these cryovolcanoes may have flattened out over time and become indistinguishable from the planet’s surface. They report their findings in a new paper accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters.

“We think we have a very good case that there have been lots of cryovolcanoes on Ceres but they have deformed,” says Sori, the lead author of the new paper.

Why is it alone?

Adding to the puzzle are the steep sides and well-defined features of Ahuna Mons—usually signs of geologic youth, Sori says. That leads to two possibilities: Ahuna Mons is just as it appears, inexplicably alone after forming relatively recently on an otherwise inactive world.

Or, the cryovolcano is not alone or unusual, and there is some process on Ceres that has destroyed its predecessors and left the young Ahuna Mons as the solitary cryovolcano on the dwarf planet, according to Sori.

Ceres has no atmosphere, so the processes that wear down volcanoes on Earth—wind, rain, and ice—aren’t possible on the dwarf planet. Sori and his colleagues hypothesized that another process, called viscous relaxation, could be at work.

Viscous relaxation is the idea that just about any solid will flow, given enough time. For example, a cold block of honey appears to be solid. But if given enough time, the block will flatten until there is no sign left of the original block structure.

On Earth, viscous relaxation is what makes glaciers flow, Sori says. The process doesn’t affect volcanoes on Earth because they are made of rock, but Ceres’ volcanoes contain ice, making viscous relaxation possible.

On Ceres, viscous relaxation could be causing older cryovolcanoes to flatten over millions of years so they are hard to discern. Ceres’ location close to the sun could make the process more pronounced, Sori says.

How fast is it flattening?

To test the idea that viscous relaxation had caused cryovolcanoes to flatten out on Ceres, Sori and his colleagues created a model using the actual dimensions of Ahuna Mons to predict how fast the mountain might be flowing. They ran the model assuming different water contents of the material that makes up the mountain—ranging from 100 percent water ice to 40 percent water ice, Sori explains.

Ahuna Mons would need to be composed of more than 40 percent water ice to be affected by viscous relaxation, they found. At this composition, Sori estimates that Ahuna Mons should be flattening at a rate of 10 to 50 meters (30 to 160 feet) per million years.

That is enough to render cryovolcanoes unrecognizable in hundreds of millions to billions of years, suggesting there could have been other cryovolcanoes on Ceres, according to the new study.

“Ahuna Mons is at most 200 million years old. It just hasn’t had time to deform,” Sori says.

Mars volcano erupted nonstop for 2 billion years

The next step for Sori and his team will be to try to identify the flattened remnants of older cryovolcanoes on Ceres. The findings could help scientists better decipher the history of how the dwarf planet formed, he added.

The new study helps scientists expand their knowledge of what might be possible on planetary bodies in our solar system, says Kelsi Singer, a postdoctoral researcher who studies icy worlds at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and was not involved with the new research.

“It would be fun to check some of the other features that are potentially older domes on Ceres to see if they fit in with the theory of how the shapes should viscously evolve over time,” she says. “Because all of the putative cryovolcanic features on other worlds are different, I think this helps to expand our inventory of what is possible.”

Source: American Geophysical Union and University of Arizona