The caucus system leaves out a wide range of voter groups, a historian argues.

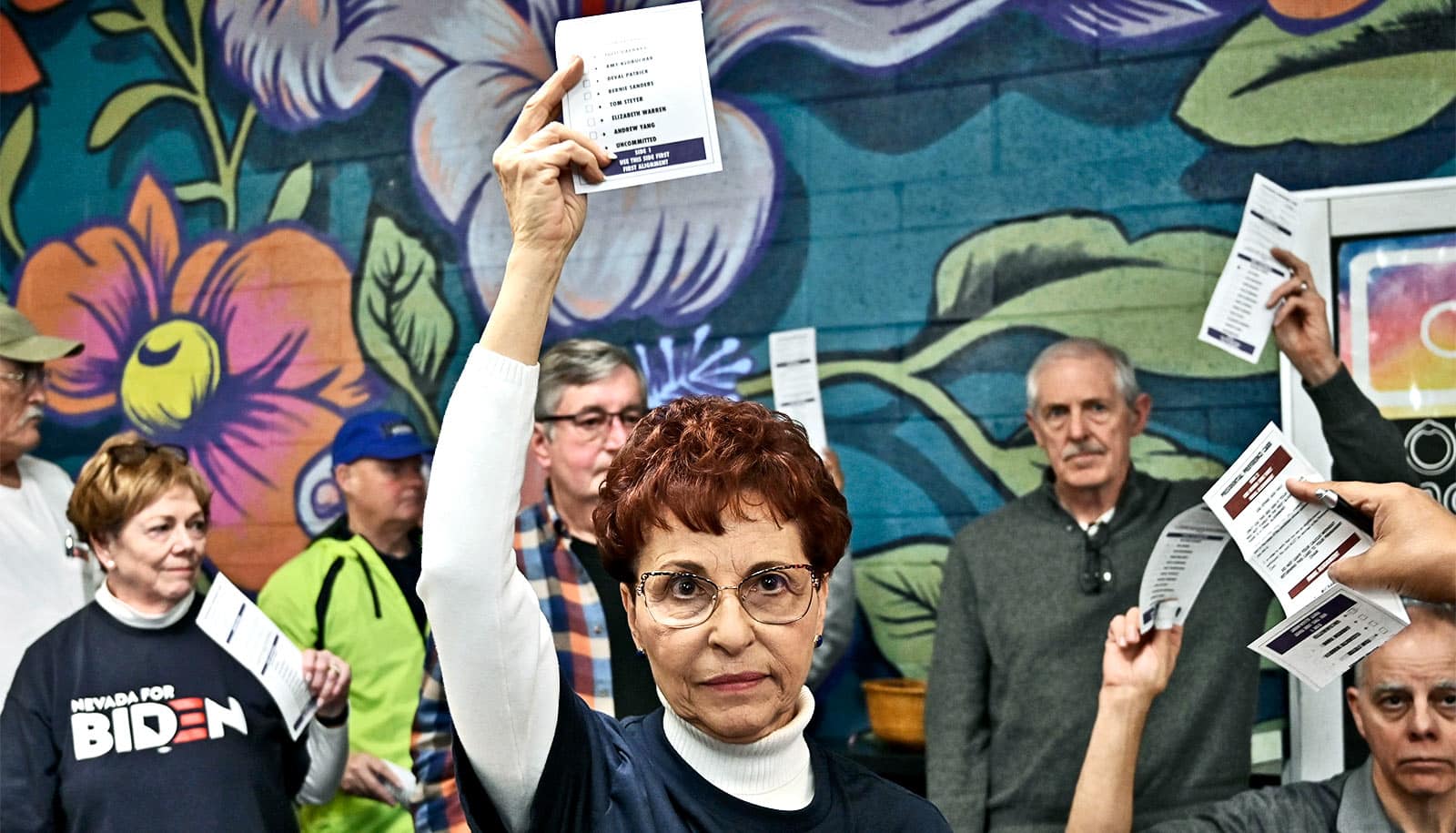

As the country’s political parties begin the process of choosing their presidential candidates, and with the second caucus in Nevada just past, questions loom about the history and legitimacy of caucus voting.

“Caucusing has a lot of accessibility problems, but not a lot of accountability.”

The Democratic Party’s Iowa caucus threw into stark relief the challenges of caucus voting, though questions of accuracy and flawed technology overshadowed the issues of voting rights.

Rabia Belt, an associate professor of law at Stanford University and a legal historian whose scholarship focuses on disability and citizenship, says the caucus system disenfranchises a huge number of voters, including people with disabilities and working parents.

Here, Belt explains the caucus system of voting and challenges to democracy:

What is the history of caucusing in presidential elections?

Caucuses are a vestige of the 19th century, when political party operatives held closed-door meetings to select national convention delegates that then voted on political candidates. Primary elections emerged during the Progressive Era at the turn of the twentieth century as a method to check party machine and political operative power through direct elections.

The national balance tipped in favor of primaries after 1968. During that election cycle, Hubert Humphrey’s manipulation of Democratic Party rules caused outrage and the subsequent creation of the McGovern-Fraser Commission to change Democratic party rules to ones that favored primaries. The Republicans followed suit.

Since then, the number of primaries has steadily increased. Now, five states [Iowa, Kentucky (just the Republicans), Nevada, North Dakota, and Wyoming] and three territories [American Samoa, the US Virgin Islands, and Guam] still use caucuses.

What’s the difference between primary voting and caucusing?

In the primaries, voters cast secret ballots—like they do in a general election—to select state delegates who go on to choose a presidential nominee at the political party’s national convention.

By contrast, caucus goers assemble in small groups in public and private dwellings to listen to fellow citizens speak about their chosen candidate before deciding in a public vote for a delegate that will carry their wishes to the national political party convention and select a presidential nominee. Primaries are state-run and financed, while caucuses are party-run and financed.

How are people disenfranchised through the caucus process? Can you describe the barriers people face?

Potential caucus goers face a number of barriers. A deaf person may be unable to understand her fellow voters without captioning or a sign language translator. A veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder may find the prospect of standing in a crowded room for hours impossible. People with autoimmune disorders cannot be in a room with many other people during peak flu season. Elderly voters or voters with physical impairments may not have the stamina to sustain them for hours of deliberation. There may not be enough [or any] accessible parking spots or accessibility in the caucus location. This is especially the case if it is a private dwelling.

Given the many challenges to disenfranchised voters, why is caucus voting allowed?

Caucusing has a lot of accessibility problems, but not a lot of accountability. The Republican National Committee addresses accessibility concerns for military voters with injuries, but not voters with disabilities in general. Both national political parties defer to state and local party operatives. State governments defer to the political parties as well. Political parties defend their practices by contending that caucuses are not state-run and they are not elections; instead, they are meetings of the political party and as such they have a right to organize themselves as they see fit.

Some state and local political parties have adopted policies and resolutions to accommodate prospective voters. These procedures are voluntary, however, and usually last-minute patchwork efforts that leave caucus sites inaccessible and disabled citizens disenfranchised and distrustful of the government.

Given party rule over this, what can people with disabilities and other challenges such as childcare do?

In the absence of proactive and robust practices by the political parties, advocates and activists have taken matters into their own hands. Organizations such as Disability Rights Iowa and the Nevada Disability Advocacy & Law Center have been sounding the alarm about inaccessible caucuses for years now and have pushed the political parties to make changes.

Reyma McCoy McDeid’s efforts are an example of what people, not the parties, have done. Ms. McDeid is a black autistic woman and the executive director of the Central Iowa Center for Independent Living. She offered the fully-ADA compliant common area at her Center for Independent Living as a caucus site. She scheduled the caucus to start at 5 PM instead of the usual 7 PM time so that those who used public transportation would be able to participate. She had several different types of seating arrangements, including yoga mats for people who needed to lay down. She provided food, a lactation room, and childcare. She had two quiet rooms available for people who were sensory- or neurodiverse. She recruited a Deaf colleague for a concurrent ASL-only caucus area. And she provided a microphone and issued ground rules that everyone needed to use it.

More broadly, what does the continued use of caucus voting say about democracy and the rights of the disabled in the US?

Voters with disabilities generally face barriers to full political participation. They want to vote the same way as their fellow citizens. Caucusing, even more than voting in a primary, is an opportunity to participate in one’s community. People with disabilities watch their friends, neighbors, and family members go off to caucus while they remain at home, and they know it is purely because of their disability that they are left behind.

Blocking access to the vote sends a message to people with disabilities that they are not wanted as political citizens. This dignitary harm is part of history and a pattern of second-class citizenship. Barriers to the political process are longstanding, and historically, people with disabilities faced express prohibitions on the right to vote. Now, more unintentional but no less harmful obstacles remain. The nonexistence of people with disabilities at caucuses is a visual reminder that full citizenship is the exclusive reserve of the able-bodied. The inclusion of people with disabilities in the democratic polity is a foundation for their participation in other areas of social and civic life.

Caucuses are not only where we decide who will represent our nation, but also the sites where we decide who will comprise it. If caucuses are the nation made local, the absence of a broad swath of the population impoverishes the conversations and communities that remain. In the short run, political parties need to work with disability organizations and individuals to build in accessible policies. Over the long term, however, it is time for this outdated democratic tradition to end.

Source: Sharon Driscoll for Stanford University