Contrary to popular belief, cartilage in human joints can repair itself, research finds.

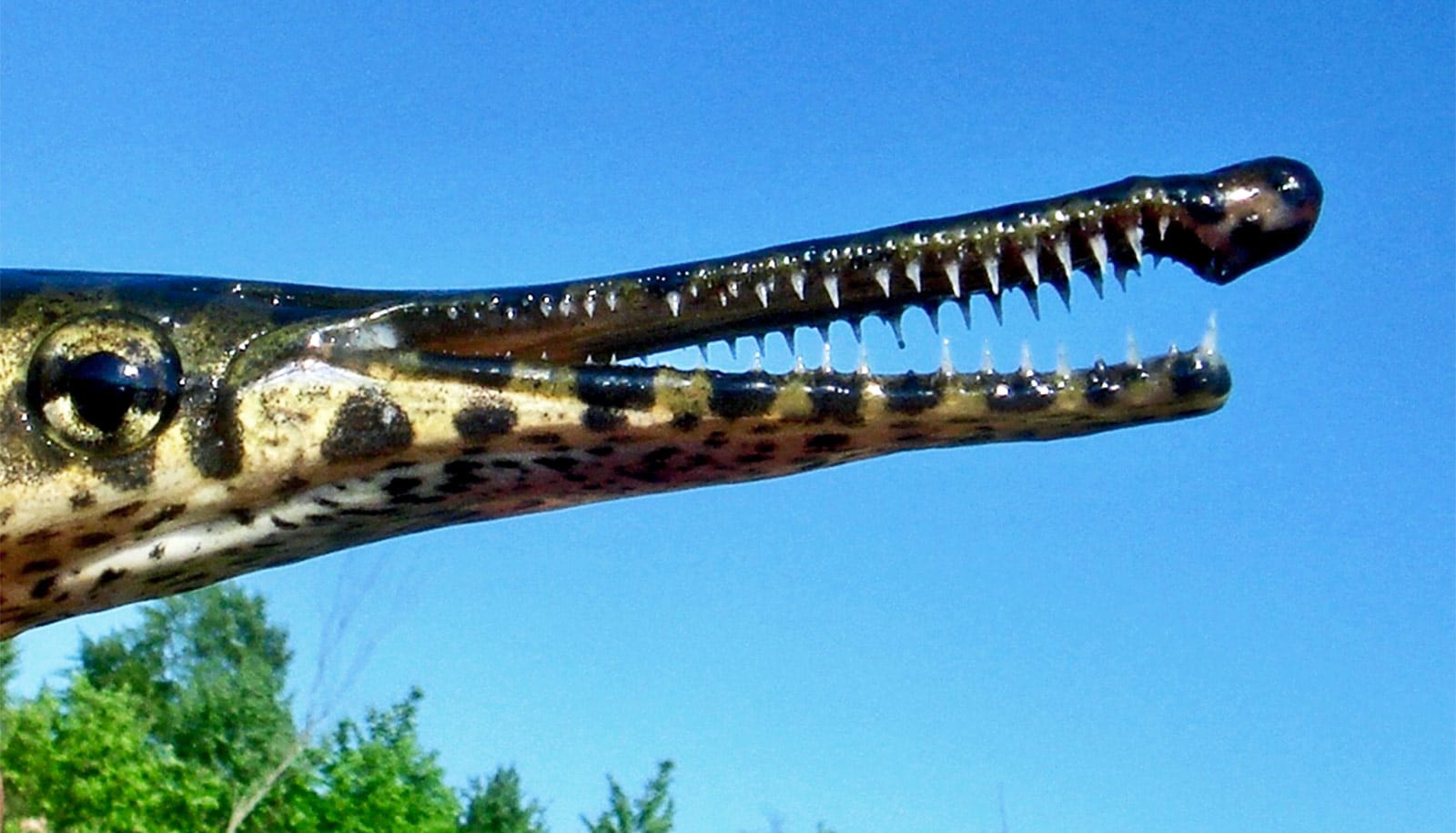

The process is similar to what creatures such as salamanders and zebrafish use to regenerate limbs, say the researchers.

As reported in Science Advances, the researchers identified a mechanism for cartilage repair that appears to be more robust in ankle joints and less so in hips. The finding could potentially lead to treatments for osteoarthritis, the most common joint disorder in the world.

“We believe that an understanding of this ‘salamander-like’ regenerative capacity in humans, and the critically missing components of this regulatory circuit, could provide the foundation for new approaches to repair joint tissues and possibly whole human limbs,” says senior author Virginia Byers Kraus, a professor in the departments of medicine, pathology, and orthopedic surgery at Duke Health.

Cartilage in our ankles, knees, and hips

Kraus and colleagues, including lead author Ming-Feng Hsueh, devised a way to determine the age of proteins using internal molecular clocks integral to amino acids, which convert one form to another with predictable regularity.

Cartilage in ankles is young, it’s middle-aged in the knee, and old in the hips.

Newly created proteins in tissue have few or no amino acid conversions; older proteins have many. Understanding this process enabled the researchers to use sensitive mass spectrometry to identify when key proteins in human cartilage, including collagens, were young, middle-aged, or old.

They found that the age of cartilage largely depended on where it resided in the body. Cartilage in ankles is young, it’s middle-aged in the knee, and old in the hips. This correlation between the age of human cartilage and its location in the body aligns with how limb repair occurs in certain animals, which more readily regenerate at the furthest tips, including the ends of legs or tails.

The finding also helps explain why injuries to people’s knees and, especially, hips take a long time to recover and often develop into arthritis, while ankle injuries heal quicker and less often become severely arthritic.

Our ‘inner salamander’ capacity

The researchers further learned that molecules called microRNA regulate this process. Not surprisingly, these microRNAs are more active in animals that are known for limb, fin, or tail repair, including salamanders, zebrafish, African fresh water fish, and lizards.

These microRNAs are also found in humans—an evolutionary artifact that provides the capability in humans for joint tissue repair. As in animals, microRNA activity varies significantly by its location: it was highest in ankles compared to knees and hips and higher in the top layer of cartilage compared to deeper layers of cartilage.

“We were excited to learn that the regulators of regeneration in the salamander limb appear to also be the controllers of joint tissue repair in the human limb,” Hsueh says. “We call it our ‘inner salamander’ capacity.”

The researchers say microRNAs could be developed as medicines that might prevent, slow, or reverse arthritis.

“We believe we could boost these regulators to fully regenerate degenerated cartilage of an arthritic joint. If we can figure out what regulators we are missing compared with salamanders, we might even be able to add the missing components back and develop a way someday to regenerate part or all of an injured human limb,” Kraus says.

“We believe this is a fundamental mechanism of repair that could be applied to many tissues, not just cartilage.”

An OARSI Collaborative Scholarship, a Collaborative Exchange Award from the Orthopaedic Research Society, and the National Institutes of Health supported the work.

Source: Duke University