Using the equivalent of facial recognition technology, researchers have analyzed the skulls of early Caribbean inhabitants and uncovered some unexpected findings.

One surprising finding was that the Caribs invaded Jamaica, Hispaniola, and the Bahamas, overturning half a century of assumptions that they never made it farther north than Guadeloupe.

Experts have long dismissed Christopher Columbus’ accounts of the Caribbean include harrowing descriptions of fierce raiders who abducted women and cannibalized men as myths, but the new study suggests he may have been telling the truth.

“I’ve spent years trying to prove Columbus wrong when he was right: There were Caribs in the northern Caribbean when he arrived,” says William Keegan, curator of Caribbean archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “We’re going to have to reinterpret everything we thought we knew.”

Columbus had recounted how peaceful Arawaks in modern-day Bahamas were terrorized by pillagers he mistakenly described as “Caniba,” the Asiatic subjects of the Grand Khan. His Spanish successors corrected the name to “Caribe” a few decades later, but the similar-sounding names led most archaeologists to chalk up the references to a mix-up: How could Caribs have been in the Bahamas when their closest outpost was nearly 1,000 miles to the south?

But skulls reveal the Carib presence in the Caribbean was far more prominent than previously thought, giving credence to Columbus’ claims. A paper on the work appears in Scientific Reports.

Three groups of people in the Caribbean

Previous studies relied on artifacts such as tools and pottery to trace the geographical origin and movement of people through the Caribbean over time. Adding a biological component brings the region’s history into sharper focus, says lead author Ann Ross, a professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University.

This will change the perspective on the people and peopling of the Caribbean.”

Ross used 3D facial “landmarks,” such as the size of an eye socket or length of a nose, to analyze more than 100 skulls dating from about CE 800 to 1542. These landmarks can act as a genetic proxy for determining how closely people are related to one another.

The analysis not only revealed three distinct Caribbean people groups, but also their migration routes, which was “really stunning,” Ross says.

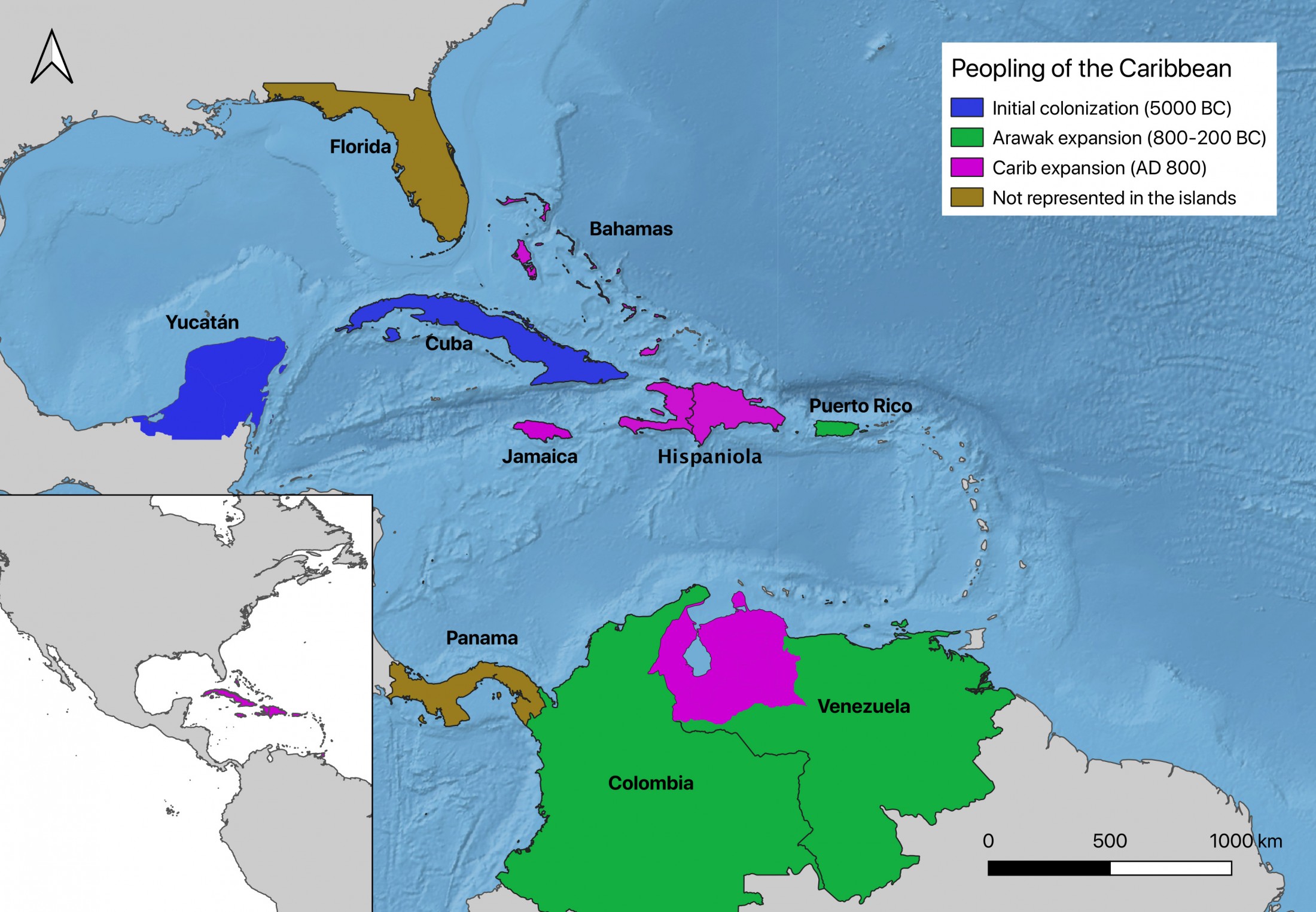

Looking at ancient faces shows the Caribbean’s earliest settlers came from the Yucatan, moving into Cuba and the Northern Antilles, which supports a previous hypothesis based on similarities in stone tools. Arawak speakers from coastal Colombia and Venezuela migrated to Puerto Rico between 800 and 200 BCE, a journey also documented in pottery.

The earliest inhabitants of the Bahamas and Hispaniola, however, were not from Cuba as commonly thought, but the Northwest Amazon—the Caribs. Around CE 800, they pushed north into Hispaniola and Jamaica and then the Bahamas where they were well established by the time Columbus arrived.

“I had been stumped for years because I didn’t have this Bahamian component,” Ross says. “Those remains were so key. This will change the perspective on the people and peopling of the Caribbean.”

For Keegan, the discovery lays to rest a puzzle that pestered him for years: why a type of pottery known as Meillacoid appears in Hispaniola by CE 800, Jamaica around 900 and the Bahamas around 1000.

“Why was this pottery so different from everything else we see? That had bothered me,” he says. “It makes sense that Meillacoid pottery is associated with the Carib expansion.”

The sudden appearance of Meillacoid pottery also corresponds with a general reshuffling of people in the Caribbean after a 1,000-year period of tranquility, further evidence that “Carib invaders were on the move,” Keegan says.

But were they cannibals?

So, was there any substance to the tales of cannibalism? Possibly, Keegan says.

Arawaks and Caribs were enemies, but they often lived side by side with occasional intermarriage before blood feuds erupted, he says.

“It’s almost a ‘Hatfields and McCoys’ kind of situation,” Keegan says. “Maybe there was some cannibalism involved. If you need to frighten your enemies, that’s a really good way to do it.”

Whether or not it was accurate, the European perception that Caribs were cannibals had a tremendous impact on the region’s history, he says. The Spanish monarchy initially insisted that indigenous people be paid for work and treated with respect, but reversed its position after receiving reports that they refused to convert to Christianity and ate human flesh.

“The crown says, ‘Well, if they’re going to behave that way, they can be enslaved,'” Keegan says. “All of a sudden, every native person in the entire Caribbean became a Carib as far as the colonists were concerned.”

Here, Ross explains the work:

What’s the fundamental new idea here?

The big idea is that anthropologists thought there were two waves of pre-Columbian migration into the Caribbean. One that came up from South America into the Lesser Antilles, like Grenada and Guadeloupe, and another that came from the Yucatán up through Cuba. What we’ve found indicates that there was a third wave, separate from the others.

What does this have to do with the Carib people?

The Carib people were the third wave. Until now, it was thought that the Carib didn’t make it past Guadeloupe. But our work indicates they made it as far as The Bahamas.

One of the things that we brought to the table with this study was an analysis of the facial morphology of pre-Columbian remains found in The Bahamas and other islands in the region.

What can you learn from analyzing these skulls?

We know that the Carib practiced artificial cranial modification, meaning that they engaged in a practice called “skull flattening” to produce particular characteristics. That’s fairly easy to spot. But to really track a population you need to focus on heritable characteristics—things that are passed on genetically. In order to do that, we focused on analyzing facial characteristics.

This involved taking detailed, three-dimensional measurements of facial characteristics from eight pre-Columbian skulls found in The Bahamas. This technique is known as geometric morphometrics and offers a scientifically robust way of determining kinship. In other words, are these skulls from the same people? Or from different groups?

We also looked at craniofacial measurements of 95 pre-Columbian skulls from across the region: Venezuela, Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Colombia, Puerto Rico, the Yucatán, Florida, and Panama.

We found that there were effectively three clusters of craniofacial similarity across the Caribbean, suggesting relatively close kinship ties. One cluster, from the so-called first wave of migration, was in Cuba and the Yucatán. The second cluster, from the Arawak expansion—or second wave—was in Venezuela, Colombia and Puerto Rico. But, and this is the exciting part, we also found that there’s a third cluster—from a Carib wave—in The Bahamas, Hispaniola, and Jamaica.

Additional researchers from NC State, the University of Missouri, and the Turks and Caicos National Museum contributed to the work.

Funding for the research came from the National Museum of the Bahamas’ Antiquities, Monuments and Museum Corporation, and the Florida Museum’s Caribbean archaeology endowment.

Source: Matt Shipman for NC State, Natalie van Hoose for University of Florida