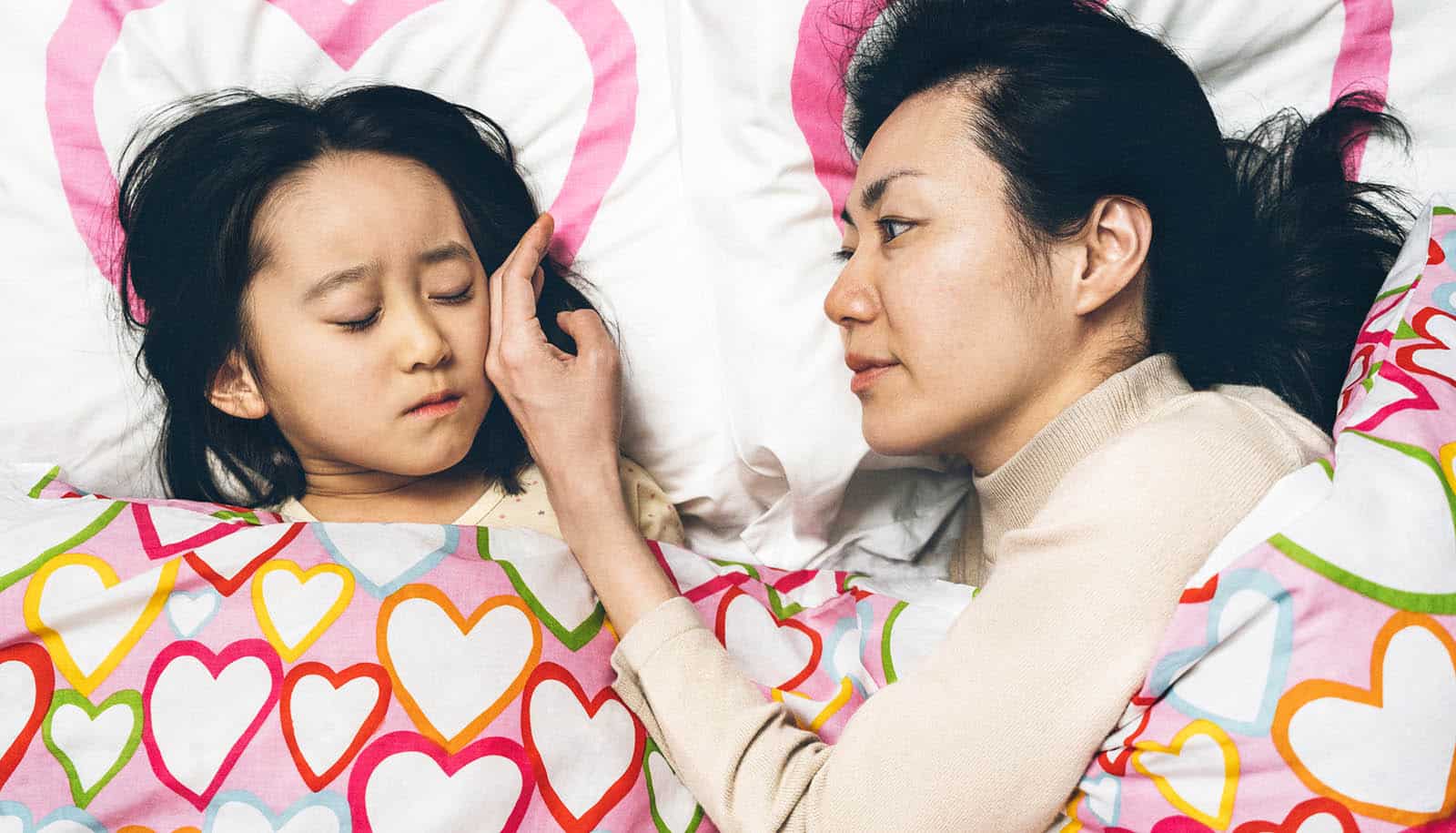

Receiving consistent warmth from a caregiver during childhood protects heart health later in life, according to a new study.

Previous research has established that childhood experience with abuse, neglect, and substance use in the home can worsen a person’s heart health throughout their life.

The findings of the new study, published in the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, are the first to frame adversity and protective factors across a large group when it comes to cardiovascular health over time, the researchers say.

Given that cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the United States, with Black adults more than twice as likely to die from CVD than white adults, the study cohort included individuals identifying as Black and white.

“We know that mitigating risk factors for cardiovascular disease must begin in childhood,” says lead author Robin Ortiz, professor in the pediatrics and population health department at New York University Langone.

“At the same time, our findings show that adversity in early childhood does not equal destiny. While adverse childhood family environments were associated with lower odds of cardiovascular health in adulthood, our findings suggest that supportive and, importantly, stable caregiving may have a stronger influence on later heart health than early adversity.”

The team of researchers analyzed a sample of more than 2,000 enrollees in the CARDIA study, a long-term study of cardiovascular disease risk beginning in young adulthood which has been following more than 5,000 Black and white adults for over 35 years to help researchers understand which early life factors raise the risk of CVD later in life.

The investigators analyzed data from this group at baseline, at which time the cohort averaged 25 years of age, and data that followed up at seven and 20 year intervals. Using scales measuring adversity in childhood including child abuse and caregiver warmth, they found that each additional unit score of overall family environment adversity and then child abuse specifically, was associated with a 3.6% and 12.8% lower odds of ideal cardiovascular health (CVH), respectively, while each additional unit score of caregiver warmth, specifically, was associated with 11.7% higher odds of cardiovascular health. CVH score was rated according to a scale of seven health metrics defined by the American Heart Association, including diet, smoking, physical activity, weight, lipids, blood pressure, and fasting glucose.

In what appeared perhaps counterintuitive to the research team, exposure to the greatest amount of caregiver warmth and greatest amount of child abuse, taken together, was associated with the lowest CVH scores. Meanwhile, exposure to the greatest amount of caregiver warmth and lowest amount of child abuse, taken together, was associated with the highest CVH scores. All findings remained consistent over 20 years of follow-up.

Exposure to caregiver warmth in childhood was associated with greatest CVH (highest scores) in adults. However, what was most unique about the findings, according to Ortiz, was that of all adults with high levels of child abuse exposure, those who also reported high levels of caregiver warmth exposure had lower CVH scores than those with high child abuse but low levels of caregiver warmth exposure. This, Ortiz interprets, suggests that while having a supportive caregiver is crucial to a life course of health, the stability and consistency of that support and warmth in childhood is just as important of a predictor of later life CVH.

Individuals who have experienced both abuse and warmth in childhood might face the inability to predict the presence of support overall in their childhood environment, Ortiz says. Individuals who are exposed to only or mostly caregiver warmth (and no, or limited abuse) are able to predict and ultimately depend on a sense of support, safety, and perhaps, physiological balance.

The findings further suggest that an unpredictable or unstable relational environment might be associated with poor health later in life, while stable or predictable support in childhood may optimize physiology and behavior to result in greater CVH later in life.

When stratifying the results by income in adulthood, the findings were more nuanced. The investigators found that the relationship between childhood adversity and CVH only stood out among those who had higher socioeconomic levels in adulthood (greater than $35,000 annually). Adverse family environments were associated with lower CVH across income levels between $35,000 to $74,000 annually, as well as with income greater than $75,000 annually, but no significant relationship between CVH and annual income less than $25,000 or between $25,00 to $34,000.

Prior studies in the field have shown that once in adulthood, it may be more difficult for people facing economic challenges to attain high levels of CVH for those with and without childhood adversity as measured in this study.

“However, for individuals in adulthood right now with higher incomes, we are able to see this relationship emerge showing how important those early environmental risk factors really are,” she says.

The hope, says Ortiz, is that this study offers insight into how supporting healthy, both supportive and stable, caregiving relationships in childhood can offer greater attainment of CVH at a population level. Future research will also focus more heavily on the complex relationship between CVH and economic hardship at different points of the life course.

“We have to address healthy caregiver relationships as well as address socioeconomic hardship,” says Ortiz. “We need policies and programs that support both caregivers and children in order to achieve greater health equity.”

Funding for the study was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with numerous institutions supporting The CARDIA Study, as well as funding in support of authors’ time including the Endocrine Society, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, and the National Institute on Aging.

Additional coauthors are from NYU Langone, Ohio University State College of Medicine, Northwestern University, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and UCLA.

Source: NYU