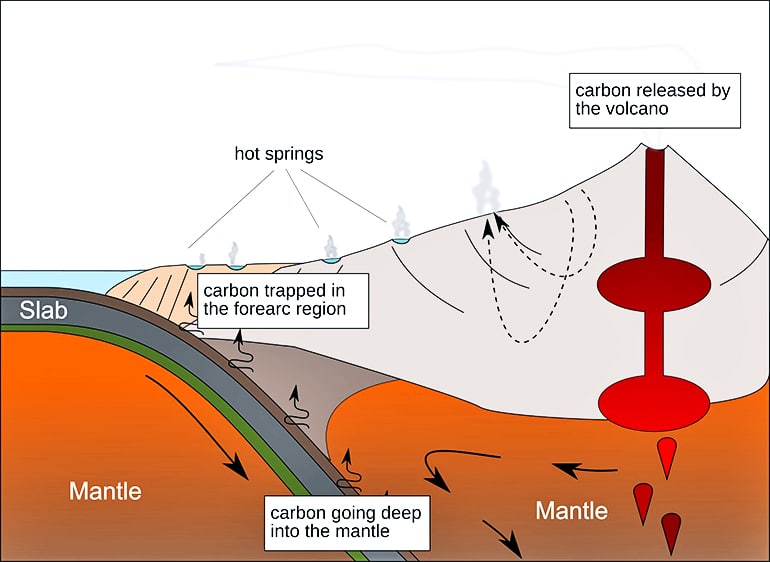

Up to about 19 percent more carbon dioxide than previously believed is removed naturally and stored underground between coastal trenches and inland chains of volcanoes, keeping the greenhouse gas from entering the atmosphere, according to a new study.

Surprisingly, subsurface microbes play a role in storing vast amounts of carbon by incorporating it in their biomass and possibly by helping to form calcite, a mineral made of calcium carbonate, the researchers found.

Greater knowledge of the long-term impact of volcanoes on carbon dioxide and how it may be buffered by chemical and biological processes is critical for evaluating natural and human impacts on the climate. Carbon dioxide is the major greenhouse gas linked to global warming.

“Our study revealed a new way that tiny microorganisms can have an outsized impact on a large-scale geological process and the Earth’s climate,” says coauthor Donato Giovannelli, a visiting scientist and former postdoctoral researcher in the marine and coastal sciences department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick who is now at the University of Naples in Italy.

The study covers how microbes alter the flow of volatile substances that include carbon, which can change from a solid or liquid to a vapor, in subduction zones. Such zones are where two tectonic plates collide, with the denser plate sinking and moving material from the surface into Earth’s interior.

The subduction, or geological process, creates deep-sea trenches and volcanic arcs, or chains of volcanoes, at the boundary of tectonic plates. Examples are in Japan and South and Central America. Arc volcanoes are hot spots for carbon dioxide emissions that re-enter the atmosphere from subducted material, which consists of marine sediment, oceanic crust and mantle rocks, Giovannelli says. The approximately 1,800-mile-thick mantle of semi-solid hot rock lies beneath the Earth’s crust.

The Earth’s core, mantle, and crust account for 90 percent of carbon. The other 10 percent is in the ocean, biosphere, and atmosphere. The subduction zone connects the Earth’s surface with its interior, and knowing how carbon moves between them is important in understanding one of the key processes on Earth and regulating the climate over tens of millions of years.

The study focused on the Nicoya Peninsula area of Costa Rica. The scientists investigated the area between the trench and the volcanic arc—the so-called forearc. The research reveals that volcanic forearc are a previously unrecognized deep sink for carbon dioxide.

The study appears in the journal Nature. Additional researchers from Rutgers; the University of Oxford; the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, Washington; and the National Research Council in Messina, Italy.

Source: Rutgers University