In a new study of CAR T-cell therapy for cancer, 93% of patients responded to the treatment.

Two physicians had major roles in a cutting-edge clinical trial using the body’s own immune cells to fight late-stage cancer, one as a researcher and one as a patient.

Senior author Patrick Reagan, an assistant professor of hematology/oncology at University of Rochester Medicine’s Wilmot Cancer Institute, helped run the national clinical investigation of CAR T-cell therapy.

“Being able to participate in this study helped to advance science, and for me, it also saved my life.”

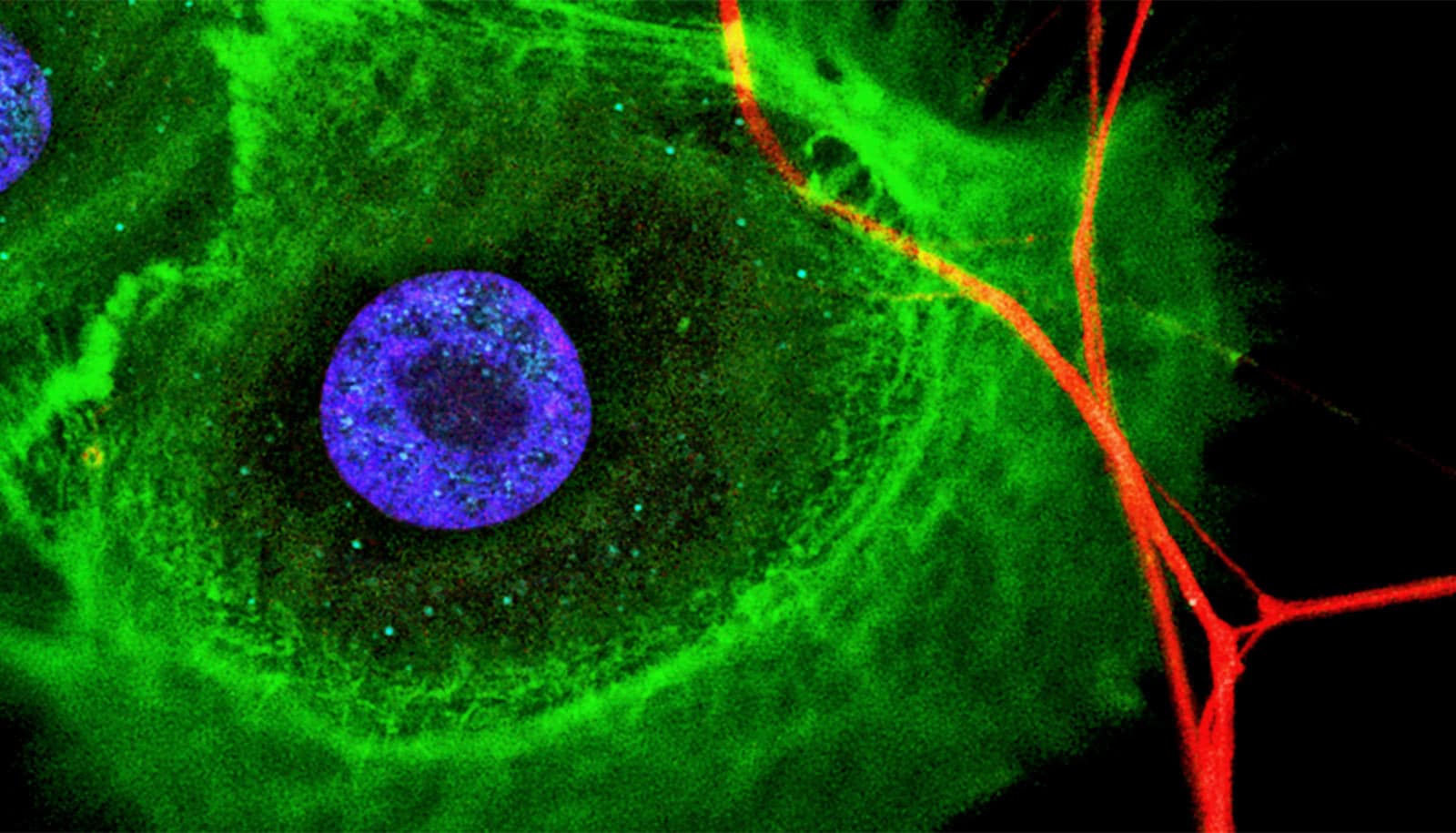

CAR T-cell therapy involves injecting billions of immune cells, which scientists have supercharged outside of the body in a bio-manufacturing facility, back into the patient to seek and destroy tumors.

Patrick Brophy, physician-in-chief at the Golisano Children’s Hospital, was a patient in the study. He suffered from a rare, aggressive subtype of lymphoma (mantle cell) and was one of the 74 individuals who took part in the trial between 2016 and 2019.

The promise of CAR T-cell therapy is based on decades of research into how the immune system interacts with cancer and how it can be manipulated to fight the disease. So far, CAR T-cell therapy is offered for lymphoma and leukemia to eligible patients. Research is continuing into other types of cancer.

Brophy and the other 73 individuals in the mantle cell lymphoma study had undergone standard therapy but their cancer returned. The median survival is less than 10 months for patients in that predicament. Mantle cell lymphoma also carries certain high-risk gene signatures and afflicts mostly adults 60 or older—although Brophy was younger, in his 50s.

“Being able to participate in this study helped to advance science, and for me, it also saved my life,” Brophy says. “Had I not been in Rochester, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity for CAR T-cell therapy through this clinical trial.”

Results showed that after a primary analysis with the majority of the patients treated, 93% responded and 67% experienced complete remission—meaning their cancer was gone—in the weeks following treatment. The overall survival rate was 83%, much higher than what doctors expect from other cancer treatments in this scenario.

“This is an important new therapy that has the potential to offer patients hope,” Reagan says. “Patients with mantle cell lymphoma who have relapsed after chemotherapy and targeted treatments have a poor prognosis and limited options. The response rates seen on this study are truly unprecedented and have been durable in a substantial number of patients.”

More than 12 months after receiving CAR T-cell therapy, 57% of the patients in the clinical trial were still in remission, the study also showed.

Before a patient can receive the reprogrammed CAR T-cells, the person must be stable enough despite having end-stage disease to withstand the life-threatening side effects and toxicities that often accompany treatment.

In Brophy’s case, the side effects were severe: He slipped into a coma and ended up in the hospital for 56 days—needing dialysis to support his kidneys. Since then, he has completely recovered and returned to his leadership position at work and to favorite activities, such as skiing, skating, hiking, and golf.

“The side effects of CAR T-cells make it difficult for some patients who have other medical problems to receive these treatments,” Reagan says. “Research is progressing, though, and we are trying to develop ways to deliver these types of therapies more safely and with improved effectiveness.”

Brophy received the treatment in October of 2018 and is doing well.

“Keeping hope is important,” Brophy says. “It’s an old adage but it’s really about family and friends, being there, and being present. Those are things I’ve focused on a lot more.”

Wilmot has been at the forefront of this type of immunotherapy since 2016, when it was selected as a national site to carry out an early clinical trial evaluating CAR T-cell therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. A year later, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the CAR T-cell treatment, called Yescarta, for that disease.

Kite Pharma, a Gilead company developed Yescarta. After the FDA approval, Wilmot again was among the first sites in the world to offer the treatment to qualifying lymphoma patients outside of the clinical trial setting.

Recently, Wilmot expanded its studies of CAR T-cells for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), indolent lymphoma, and is planning a trial for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The research appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Texas. The researchers first reported the results at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2019. Kite funded the study.

Source: University of Rochester