New research shows a completely new way in which cancer cells repair the damage that can otherwise kill them.

In both normal cells and cancer cells, the cell membrane acts as the skin of the cells. And damage to the membrane can be life threatening. The interior of cells is fluid, and if a hole is made in the membrane, the cell simply floats out and dies—a bit like a hole in a water balloon. Therefore, damage to the cell membrane must be repaired quickly.

The new research shows that cancer cells use a technique called macropinocytosis to fix themselves up. The technique, which is already a known tool for cells in other contexts, consists of the cancer cells pulling the intact cell membrane in over the damaged area and sealing the hole in a matter of minutes.

Next, the damaged part of the cell membrane is separated into small spheres and transported to the cells’ “stomach”—lysosomes—where they are broken down.

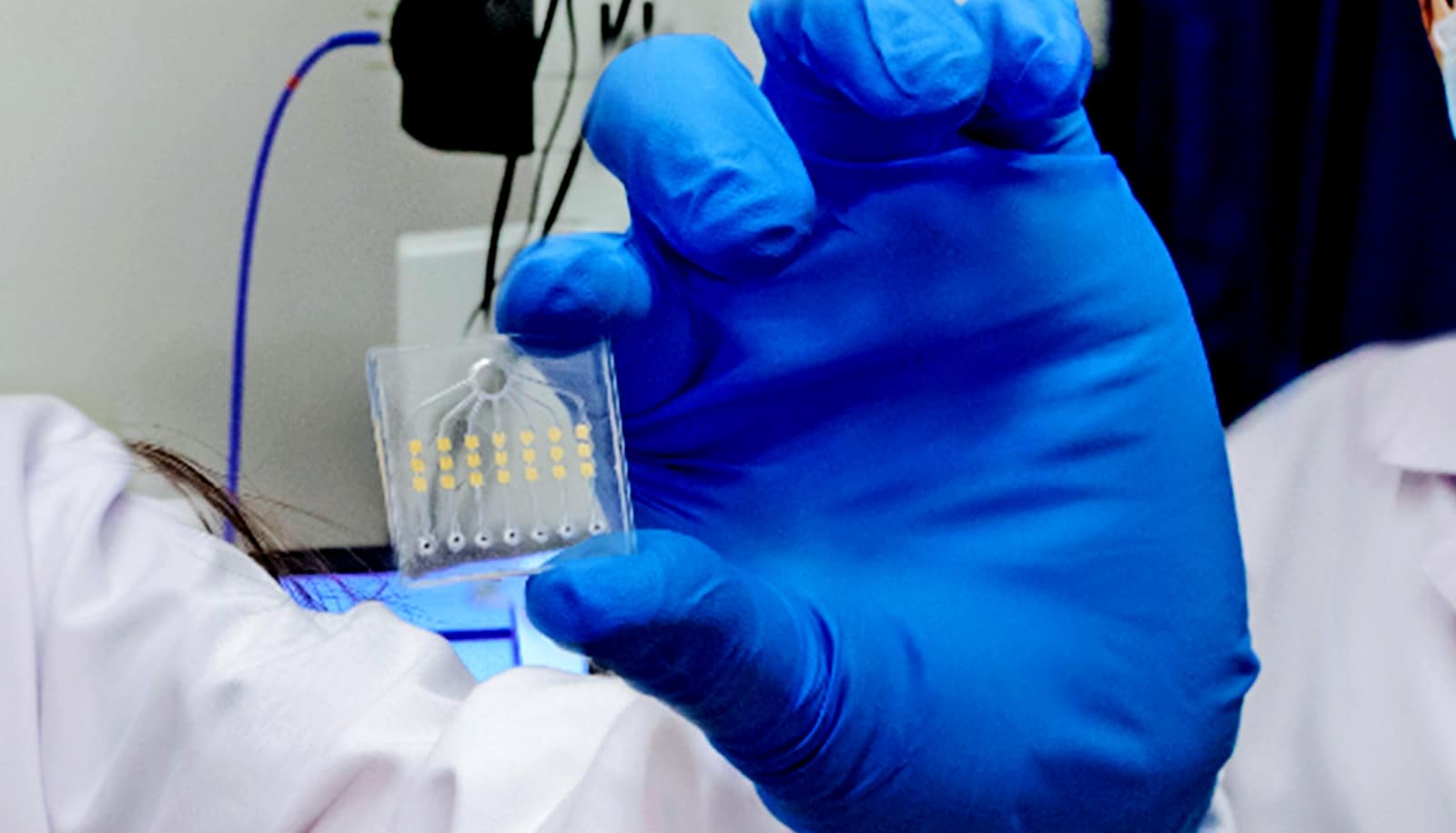

In the laboratory, the researchers damaged the membrane of the cancer cells using a laser that shoots small holes in the membrane and triggers macropinocytosis. They wanted to see if blocking the process could prevent the cancer cells from repairing the damage.

“Our research provides very basic knowledge about how cancer cells survive. In our experiments, we have also shown that cancer cells die if the process is inhibited, and this points towards macropinocytosis as a target for future treatment. It is a long-term perspective, but it is interesting,” says group leader Jesper Nylandsted from the Danish Cancer Society’s Research Center and the University of Copenhagen. Nylandsted has, for many years, investigated how cancer cells repair their membranes.

One of the most dangerous properties of cancer is when the disease spreads in the body. If tumors occur in new parts of the body, the disease becomes more difficult to treat and typically requires more extensive forms of treatment. It is also when cancer cells spread through the body’s tissues that they are particularly prone to damage to their membrane.

Researchers at the Danish Cancer Society have previously shown how cancer cells can use another technique to repair the membrane, tying off the damaged part, like when a lizard throws its tail.

The new experiments in the laboratory could indicate that aggressive cancer cells especially use macropinocytosis. This may be due to the fact that the cancer cell has the opportunity to reuse the damaged membrane when it is degraded in the lysosomes. This type of recycling is useful for cancer cells because they divide frequently, requiring large amounts of energy and material for the new cells.

And although the researchers have now published the new results, their work is not over.

“We continue to work and investigate how cancer cells protect their membranes. In connection with macropinocytosis in particular, it is also interesting to see what happens after the membrane is closed. We believe that the first patching is a bit rough and that a more thorough repair of the membrane is needed afterwards. It can be another weak point in the cancer cells, and is something we want to examine closer,” postdoc Stine Lauritzen Sønder says.

The research appears in Science Advances.

Additional researchers are from the Danish Cancer Society, the University of Copenhagen, the University of Southern Denmark, and the Biotech Research and Innovation Centre at the University of Copenhagen.

Source: University of Copenhagen