Traditional cameras—even those on the thinnest of cell phones—cannot be truly flat due to their optics: lenses that require a certain shape and size in order to function.

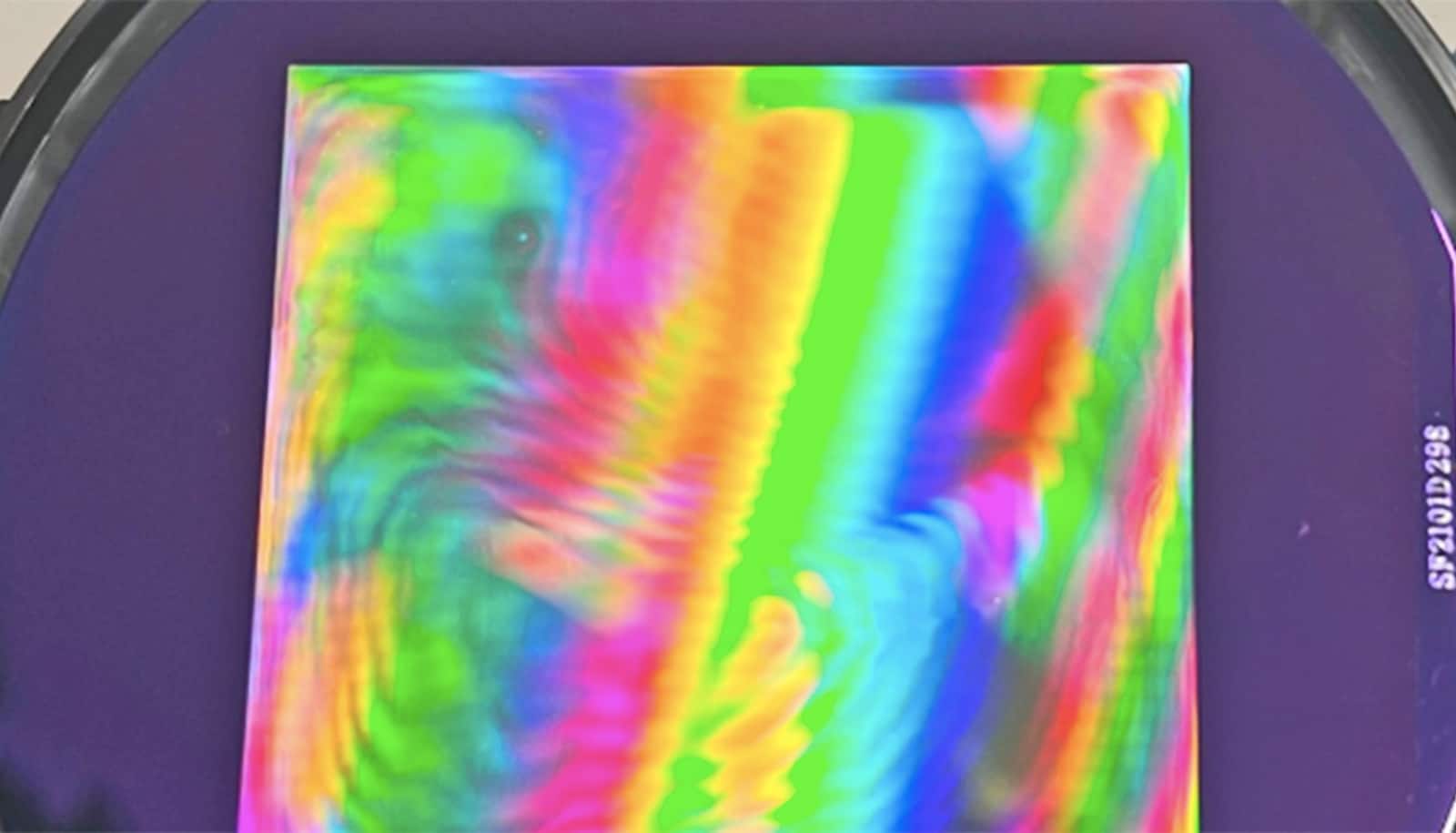

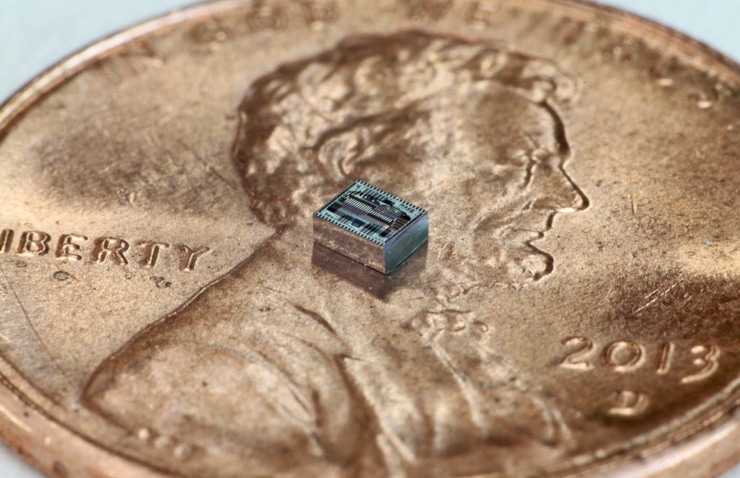

A new camera design replaces the lenses with an ultra-thin optical phased array (OPA) that does computationally what lenses do using large pieces of glass: it manipulates incoming light to capture an image.

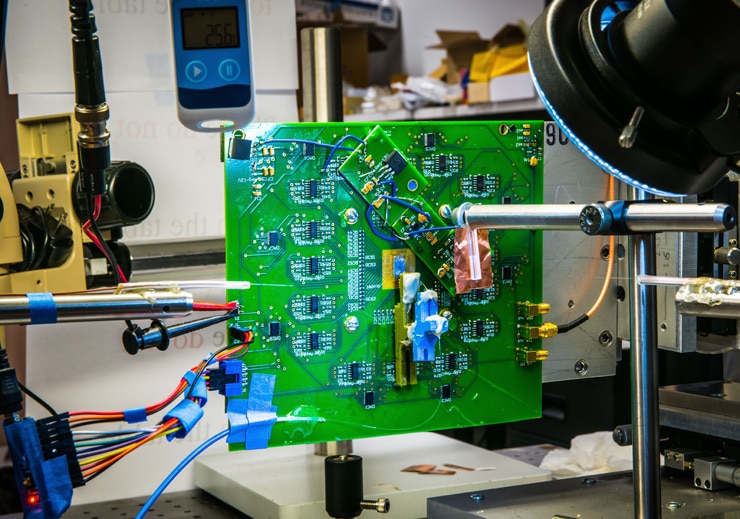

Lenses have a curve that bends the path of incoming light and focuses it onto a piece of film or, in the case of digital cameras, an image sensor. The OPA has a large array of light receivers, each of which can individually add a tightly controlled time delay (or phase shift) to the light it receives, enabling the camera to selectively look in different directions and focus on different things.

“Here, like most other things in life, timing is everything. With our new system, you can selectively look in a desired direction and at a very small part of the picture in front of you at any given time, by controlling the timing with femto-second—quadrillionth of a second—precision,” says Ali Hajimiri, professor of electrical engineering and medical engineering at California Institute of Technology and principal investigator of a paper in OSA Technical Digest.

“We’ve created a single thin layer of integrated silicon photonics that emulates the lens and sensor of a digital camera, reducing the thickness and cost of digital cameras. It can mimic a regular lens, but can switch from a fish-eye to a telephoto lens instantaneously—with just a simple adjustment in the way the array receives light.”

Camera prototype is thinner than a dime

Phased arrays, which are used in wireless communication and radar, are collections of individual transmitters, all sending out the same signal as waves. These waves interfere with each other constructively and destructively, amplifying the signal in one direction while canceling it out elsewhere. So, an array can create a tightly focused beam of signal, which can be steered in different directions by staggering the timing of transmissions made at various points across the array.

A similar principle is used in reverse in an optical phased array receiver, which is the basis for the new camera. Light waves that are received by each element across the array cancel each other from all directions, except for one. In that direction, the waves amplify each other to create a focused “gaze” that can be electronically controlled.

“What the camera does is similar to looking through a thin straw and scanning it across the field of view. We can form an image at an incredibly fast speed by manipulating the light instead of moving a mechanical object,” says graduate student Reza Fatemi, the paper’s lead author.

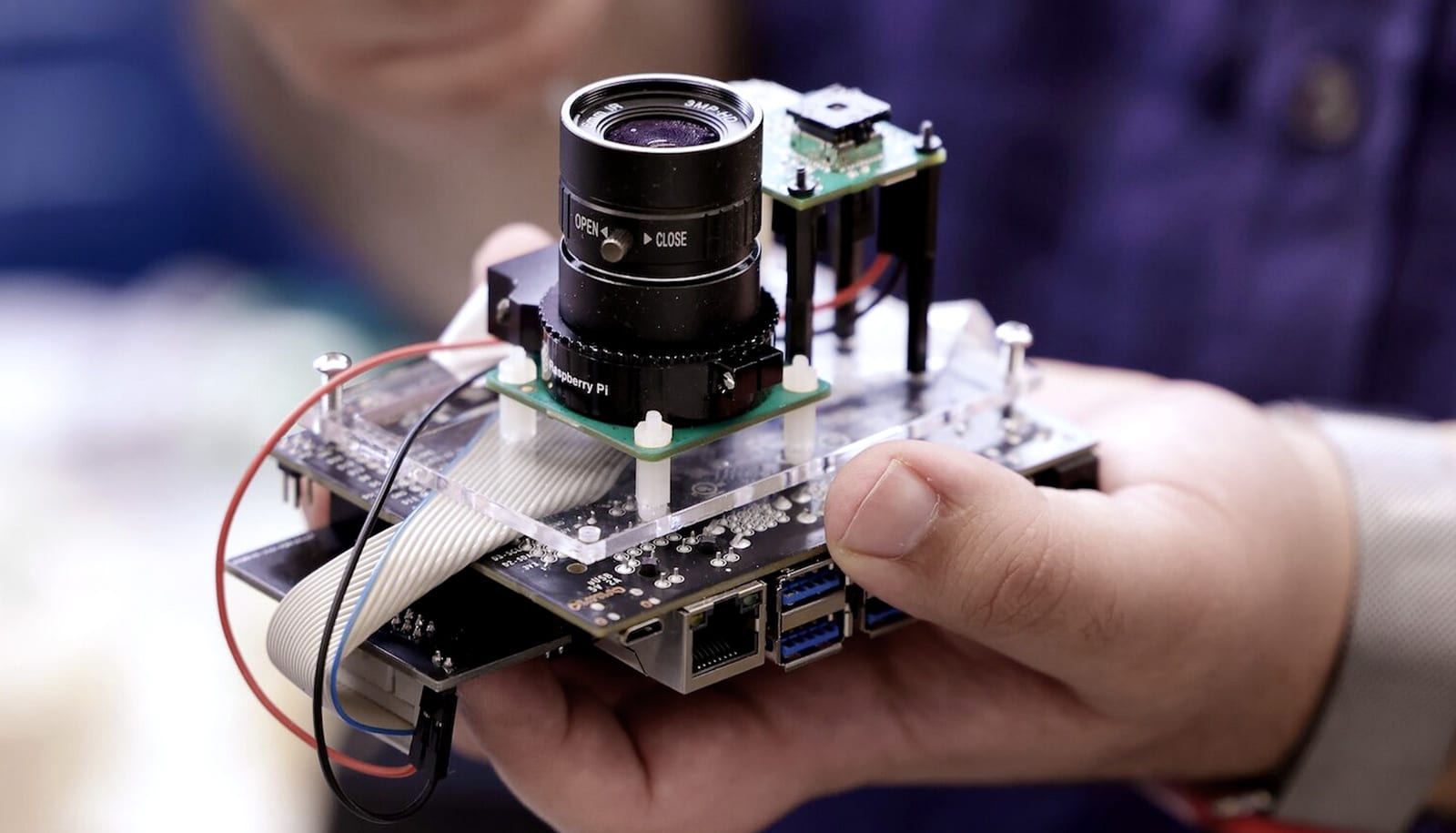

Last year, Hajimiri’s team rolled out a one-dimensional version of the camera that was capable of detecting images in a line, such that it acted like a lensless barcode reader but with no mechanically moving parts.

New camera uses just 1 photon per pixel

This year’s advance was to build the first two-dimensional array capable of creating a full image. This first 2D lensless camera has an array composed of just 64 light receivers in an 8 by 8 grid. The resulting image has low resolution—but the system represents a proof of concept for a fundamental rethinking of camera technology, researchers say.

“The applications are endless,” says graduate student and coauthor Behrooz Abiri. “Even in today’s smartphones, the camera is the component that limits how thin your phone can get. Once scaled up, this technology can make lenses and thick cameras obsolete. It may even have implications for astronomy by enabling ultra-light, ultra-thin enormous flat telescopes on the ground or in space.”

“The ability to control all the optical properties of a camera electronically using a paper-thin layer of low-cost silicon photonics without any mechanical movement, lenses, or mirrors, opens a new world of imagers that could look like wallpaper, blinds, or even wearable fabric,” says Hajimiri.

The team will next work on scaling up the camera by designing chips that enable much larger receivers with higher resolution and sensitivity.

Source: Caltech