The recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York on May 14 is set apart from the many mass shootings that happen yearly in the US by white nationalism.

Rather than indiscriminately shooting, the 18-year-old suspect targeted a supermarket in a predominantly Black neighborhood. He allegedly wrote a white supremacist manifesto online, traveled about 200 miles to the store, and livestreamed the attack, according to authorities.

This is part of a growing trend in the US that includes the 2015 murder of worshippers at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina by a professed white supremacist; the 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life Congregation Pittsburgh synagogue; the 2019 Walmart shooting targeting Latinx residents of El Paso, Texas; and the 2021 shooting in an Atlanta, Georgia spa targeting Asian Americans.

Here, Shirin Sinnar, professor of law at Stanford University and the author of a new paper in the California Law Review, discusses the scale of white supremacist violence in the US and the rise of hate crimes:

It has been reported that the suspect at the Buffalo supermarket made racist remarks during the attack and to police after. The combination of hate and freely available guns is lethal. Has there been a measurable rise in hate crimes in the US?

The FBI Uniform Crime Reporting program issues annual national hate crime statistics, and its most recent data show that hate crimes are at their highest level in over a decade.

Other sources also report a rise in hate crimes, including a study of police data on hate crimes in the largest US cities that found a substantial increase in anti-Asian hate crimes.

Most data sources on hate crimes have serious flaws, however. The FBI relies on voluntary reporting from law enforcement agencies around the country, and an overwhelming majority of law enforcement agencies fail to report any hate crimes in their jurisdiction.

These sources almost certainly underreport real numbers for other reasons including the reluctance of many victims to report incidents to the police.

Do white nationalist attacks seem to be by individuals acting alone? Or are they part of the organized white nationalists, such as the Proud Boys who showed up at the Capitol on January 6? Is there a connection?

Security agencies often describe white supremacist violence as perpetrated primarily by lone actors. But scholars point to connections across incidents and organizations.

Historian Kathleen Belew describes individual incidents as part of a “white power movement” that united the Klan, neo-Nazis, right-wing militias, and others beginning in the 1970s.

Even when those committing violence do not coordinate with one another, they often draw on a set of common ideas disseminated through internet networks, video games, and popular culture. That idea includes the “great replacement theory” that has now shown up in the manifesto of the Buffalo shooter and in other mass shootings, including the Christchurch, New Zealand mosque massacre and the 2019 shooting targeting Latinx shoppers in El Paso, Texas.

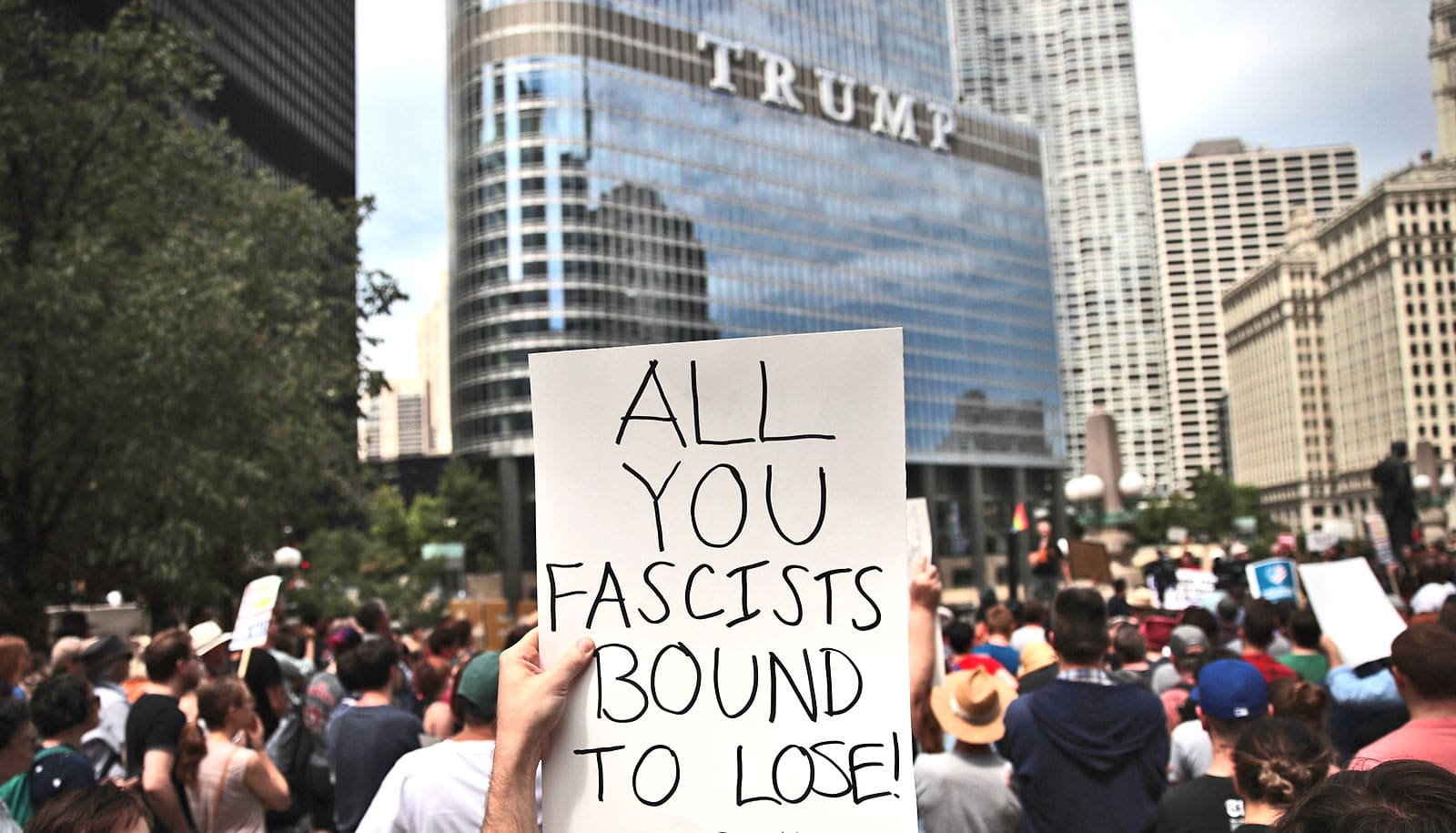

The idea that white people are in danger of demographic replacement by immigrants and other nonwhite populations, and that “elites” are driving that replacement, is increasingly common in “mainstream” discourse, such as Fox host Tucker Carlson’s highly popular cable news show.

Racial resentment appears to be fueling political mobilization and violence on the right beyond mass shootings. For example, political scientist Robert Pape’s study of over 700 people charged with storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021, concluded that participants came from counties where the white population share is declining fastest.

Is there a connection to political discourse and the language our political leaders use? What can be done to counter this rise in hate crimes?

A growing number of empirical studies substantiate the idea that high-profile political speech and government policies towards racial minority groups can influence the levels of hate crimes committed against those groups.

For instance, studies have shown an increase in hate crimes after political events, like the election of President Trump or the UK Brexit referendum, that change perceptions of social norms such as the acceptability of anti-immigrant views. But the relationship between government rhetoric or policies and hate crimes can be complicated: while exclusionary speech and policies can embolden people to commit hate crimes against those groups, perceptions of political gains by racial minority groups can also invite violent backlash.

We should be deeply concerned about the normalization of not only ideas like the “great replacement,” but also the willingness to use political violence in our culture. Recent polling of Americans suggest that one in three Americans think that political violence against the government can be justified, a greater share than reported in earlier polls over the last two decades.

All of this suggests the importance of addressing racist and other political violence in a holistic fashion. Beyond law enforcement responses, that means addressing inflammatory political and media rhetoric, online disinformation and hate speech, the easy availability of guns, white supremacy within certain state institutions, and our insufficient national reckoning with our history of racist violence and exclusion.

While reserving judgement on the motivation for Buffalo shooting until the investigation is completed, President Biden said that any “racially motivated hate crime is abhorrent to the very fabric of this nation. Any act of domestic terrorism, including an act perpetrated in the name of a repugnant white nationalist ideology, is antithetical to everything we stand for in America.”

What are the differences between a racially motivated hate crime and an act of domestic terrorism and does it matter for legal and policy responses?

The Buffalo shooting, from what we know, appears to meet common legal definitions of both a “hate crime” and “terrorism”: it is both a crime targeting a particular racial group and an act of violence with a political and ideological motive.

As I have argued in my academic work, the “hate crimes” and “terrorism” frames emerged from separate historical roots and continue to diverge in how they conceptualize and address political violence.

Yet, despite their differences, neither of these frames is ideal. The hate crimes frame addresses white supremacist violence as a problem of individual perpetrators, to be countered by dubious after-the-fact remedies such as sentence enhancements.

But applying the terrorism frame risks expanding and entrenching the problems of US counterterrorism, such as the limited accountability of the national security apparatus, abusive “preemptive” law enforcement and surveillance practices, and the targeting of subordinated communities. In my view, countering white supremacist violence should begin with a revisiting of both the hate crimes and terrorism frames that dominate our law and culture.

Source: Stanford University