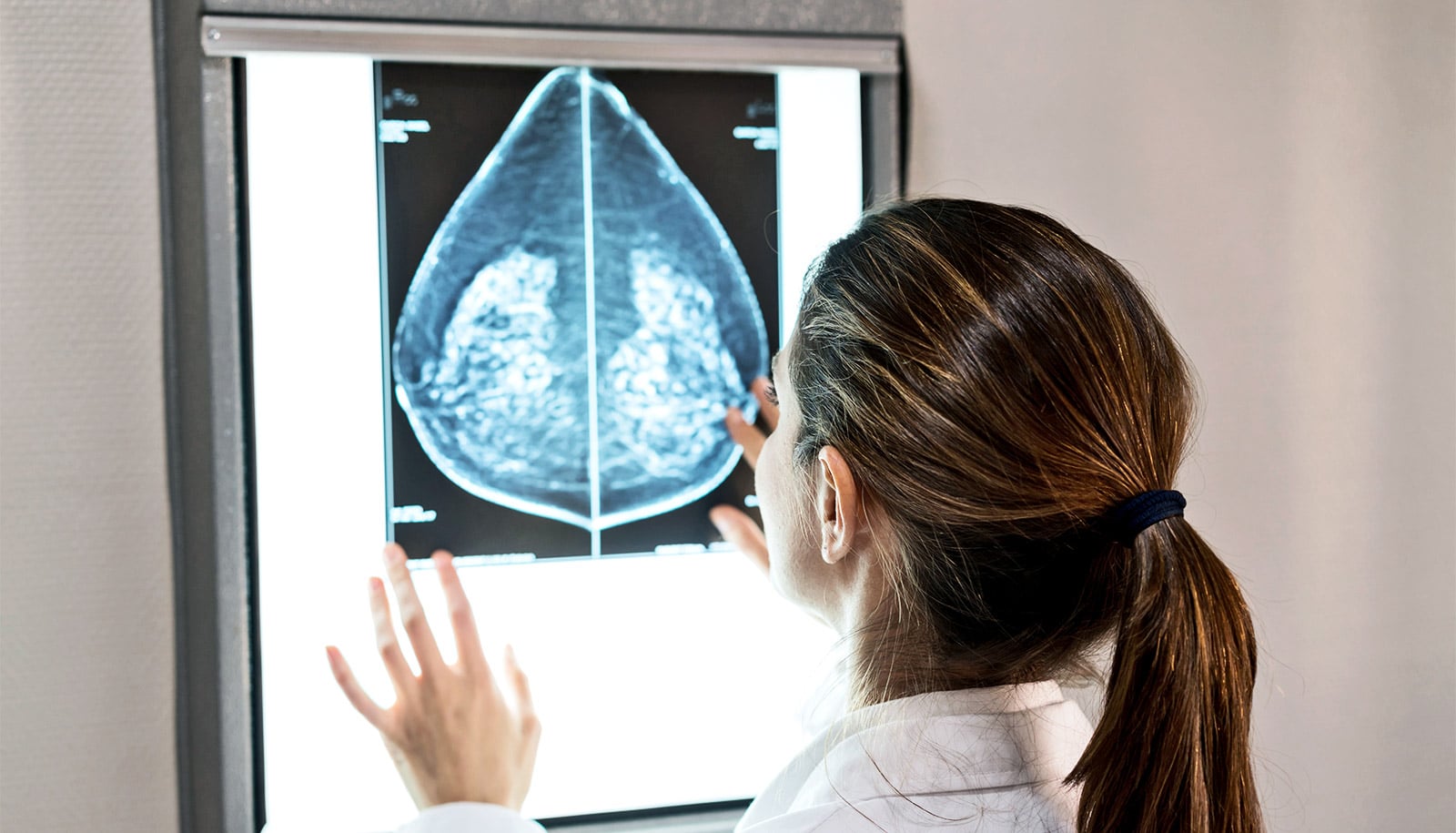

A new imaging approach for breast cancer uses 35 biomarkers to identify different cell types in breast tumors and their surrounding areas.

The current standard tests single markers. The new approach, which appears in Nature, increases the precision of tumor analysis and classification—and improves personalized diagnostics for breast cancer patients.

Breast cancer progression can vary significantly among patients. Even within the same tumor, different areas may include different types of cells and different tumor structures. This heterogeneity makes it challenging to ascertain the severity of a tumor and assess its molecular subtype, which affects the precision of diagnosis and the choice of the most effective treatment approach. More detailed characterization of a breast cancer tissue could help improve a treatment’s chances of success and may decrease the risk of relapse.

Bernd Bodenmiller, professor of quantitative biology at the University of Zurich, leads a research group that has been able to refine the pathological classification of breast cancer using imaging mass cytometry. This method enables scientists to simultaneously visualize and analyze multiple biomarkers to generate information-rich digital images of tissue sections.

In their study, the researchers quantified 35 protein biomarkers in breast cancer patients. “This created an unprecedented view of a tumor’s cellular landscape and the surrounding tissue, which enabled us to determine whether more complex biomarkers exist for clinical outcome,” explains Jana Fischer, co-first author of the study.

The team of researchers analyzed hundreds of tissue sections from 350 breast cancer patients and categorized the many cell components and how they are organized in cellular communities and form tumor tissues.

“Four categories of breast cancer are routinely classified in the clinic, but our new analysis allows us to go further and identify multiple detailed subcategories of breast cancer. The danger from these diverse tumors can be very different, and each type could respond to therapy in its own way,” explains co-first author Hartland Jackson.

This finding has the potential to change clinical practice. The new subgroups of breast cancer patients vary in their molecular profiles. Bodenmiller and his team are now working on finding out which drugs are best able to combat tumor cells with a specific molecular profile.

“By improving our ability to describe cellular features and categories as well as our ability to precisely identify patients that have high or low risk breast cancer, we’re opening up new possibilities for precision medicine,” says Bodenmiller.

Source: University of Zurich