As many as one in three women treated for breast cancer undergo unnecessary procedures, but a new method for diagnosing it could do a better job distinguishing between benign and aggressive tumors.

Researchers are developing a new pill that makes breast cancer tumors light up when exposed to infrared light. They’ve already demonstrated that the concept works in mice.

Mammography is an imprecise tool. About a third of breast cancer patients treated with surgery or chemotherapy have tumors that are benign or so slow-growing that they would never have become life-threatening.

“We overspend $4 billion per year on the diagnosis and treatment of cancers that women would never die from.”

In other women, dense breast tissue hides the presence of lumps and can result in death from treatable cancers. What’s more, mammograms are notoriously uncomfortable.

“We overspend $4 billion per year on the diagnosis and treatment of cancers that women would never die from,” says Greg Thurber, assistant professor of chemical engineering and biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan. “If we go to molecular imaging, we can see which tumors need to be treated.”

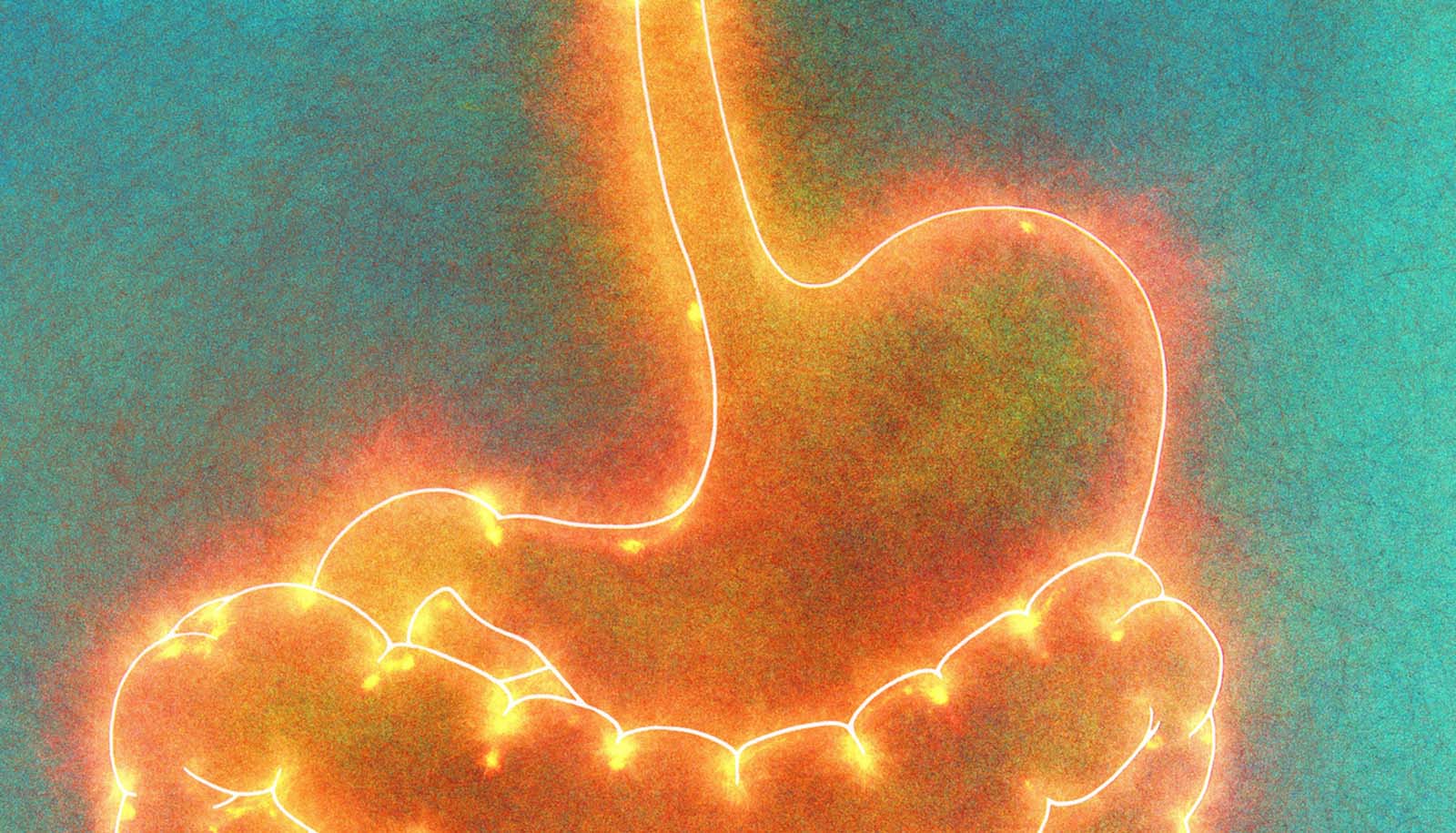

As reported in Molecular Pharmaceutics, the move could also catch cancers that would have gone undetected. The method uses a dye that responds to infrared light to tag a molecule commonly found on tumor cells, in the blood vessels that feed tumors, and in inflamed tissue.

By providing specific information on the types of molecules on the surface of the tumor cells, doctors can better distinguish a malignant cancer from a benign tumor.

Compared to visible light, infrared light penetrates the body easily—it can get to all depths of the breast without an X-ray’s tiny risk of disrupting DNA and seeding a new tumor.

Using a dye delivered orally rather than directly into a vein also improves the safety of screening, as a few patients in 10,000 can have severe reactions to intravenous dyes. These small risks turn out to be significant when tens of millions of women receive screenings every year in the US alone.

But designing a pill that can carry the dye to the tumor is no easy task.

“To get a molecule absorbed into the bloodstream, it needs to be small and greasy. But an imaging agent needs to be larger and water-soluble. So you need exact opposite properties,” Thurber says.

Anxiety meds more likely after breast cancer scare

Fortunately, they weren’t the only researchers looking for a molecule that could get from the digestive system to a tumor. The pharmaceutical company Merck was working on a new treatment for cancer and related diseases. They got as far as phase II clinical trials demonstrating its safety, but it turned out to be ineffective.

“It’s actually based on a failed drug,” Thurber says. “It binds to the target, but it doesn’t do anything, which makes it perfect for imaging.”

Researchers have already showed that the targeting molecule can make it through the stomach unscathed, and the liver also gives it a pass, so it can travel through the bloodstream. The team attached a molecule that fluoresces when it is struck with infrared light to this drug. Then, they gave the drug to mice that had breast cancer, and saw the tumors light up.

Should Medicare toss this mammogram add-on?

David Smith, professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the College of Pharmacy collaborated on the study. The Foundation for Studying and Combating Cancer and the National Institutes of Health supported the work.

Source: University of Michigan