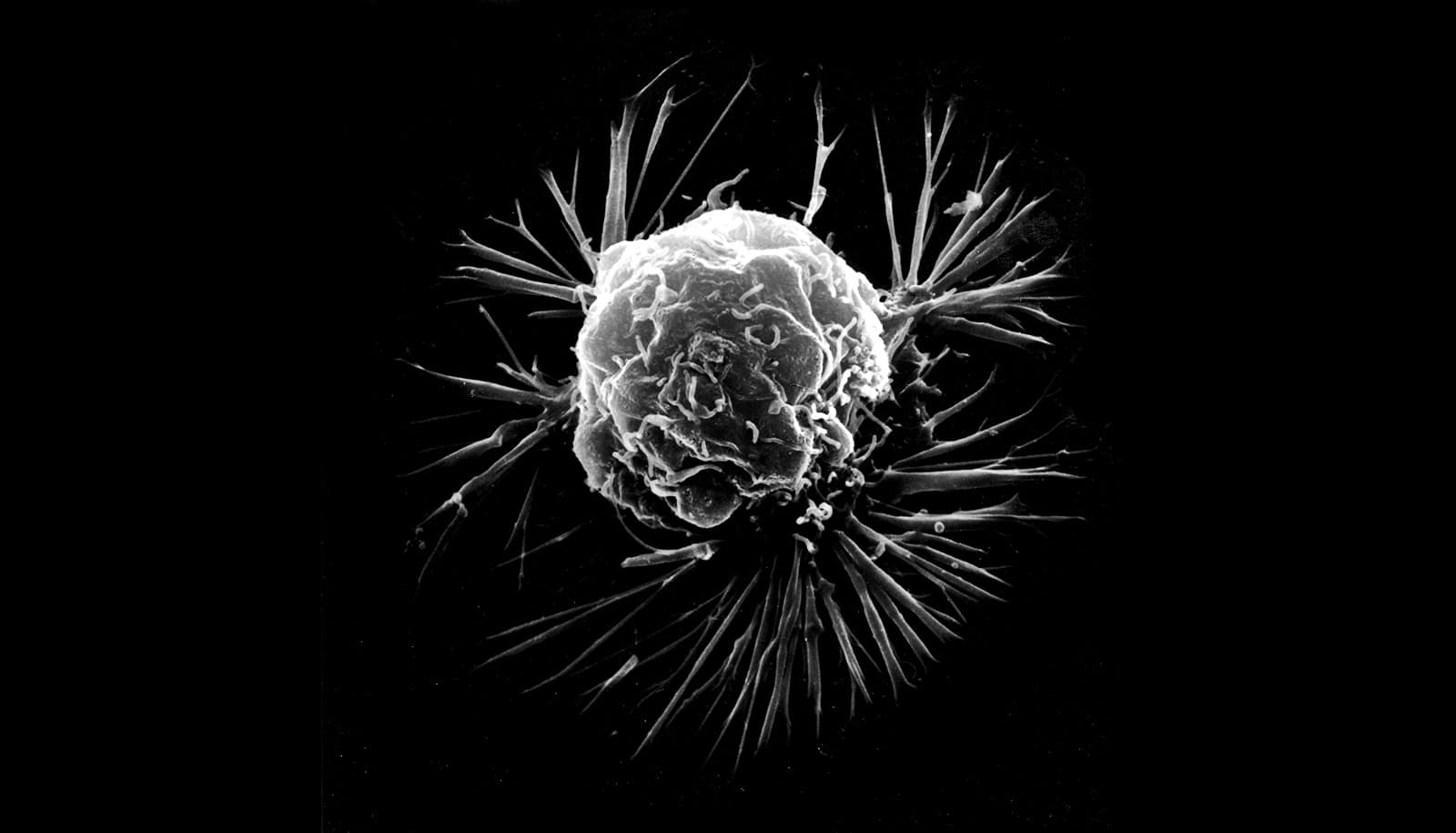

Breast cancer cells can shift their metabolism to metastasize, according to a new study.

Instead of cycling sugar (glucose) for energy, the cells preferentially use mitochondrial metabolism, researchers say.

The discovery could lead to better strategies to prevent the spread of cancer cells to other organs in the body, which could in turn reduce mortality.

“This has important potential clinical implications because it suggests that drugs targeting mitochondrial metabolism may have efficacy for preventing metastatic spread in patients,” says Devon A. Lawson, assistant professor in the physiology and biophysics department at the University of California, Irvine.

“Historically, tumors were thought to contain dysfunctional mitochondria and be principally sustained by anaerobic glycolysis, or Warburg metabolism. Our work challenges that dogma and shows that breast cancer cells use mitochondrial metabolism during metastatic spread.”

Despite major advances in the detection and treatment of early stage disease, metastasis—when cancer cells in the breast spread to other organs in the body—accounts for approximately 40,000 deaths among women in the US each year. It is the number one cause of nearly all mortality associated with breast cancer.

Previous work suggests that rare primary tumor cells seeds metastasis. The cells have unique biological properties that enable them to spread, causing the cancer to take hold in other locations in the body.

While properties promoting cell motility and migration are well studied, mechanisms governing the seeding and establishment of small collections of cancer cells in distal tissues are not.

This is in part because researchers can’t study metastatic seeding in humans, and because it is technically challenging to detect and analyze rare cells at this transient stage in animal models.

“Through our research, we established a robust new method for identifying global transcriptomic changes in rare metastatic cells during seeding using single-cell RNA-sequencing and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of breast cancer,” says first author Ryan Davis, a doctoral student in the Lawson laboratory.

“We found that metastatic cells harbor distinct RNA molecules that are highly predictive of poor survival in patients and alter metabolism in a way that can be targeted therapeutically.”

The paper appears in Nature Cell Biology.

The National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Team Michelle and Friends non-profit organization, the Suzette Kirby Breast Cancer Research Fund, the V Foundation, a Cancer Center Support Grant, and a Center for Complex Biological Systems Support Grant funded the work.

Source: UC Irvine