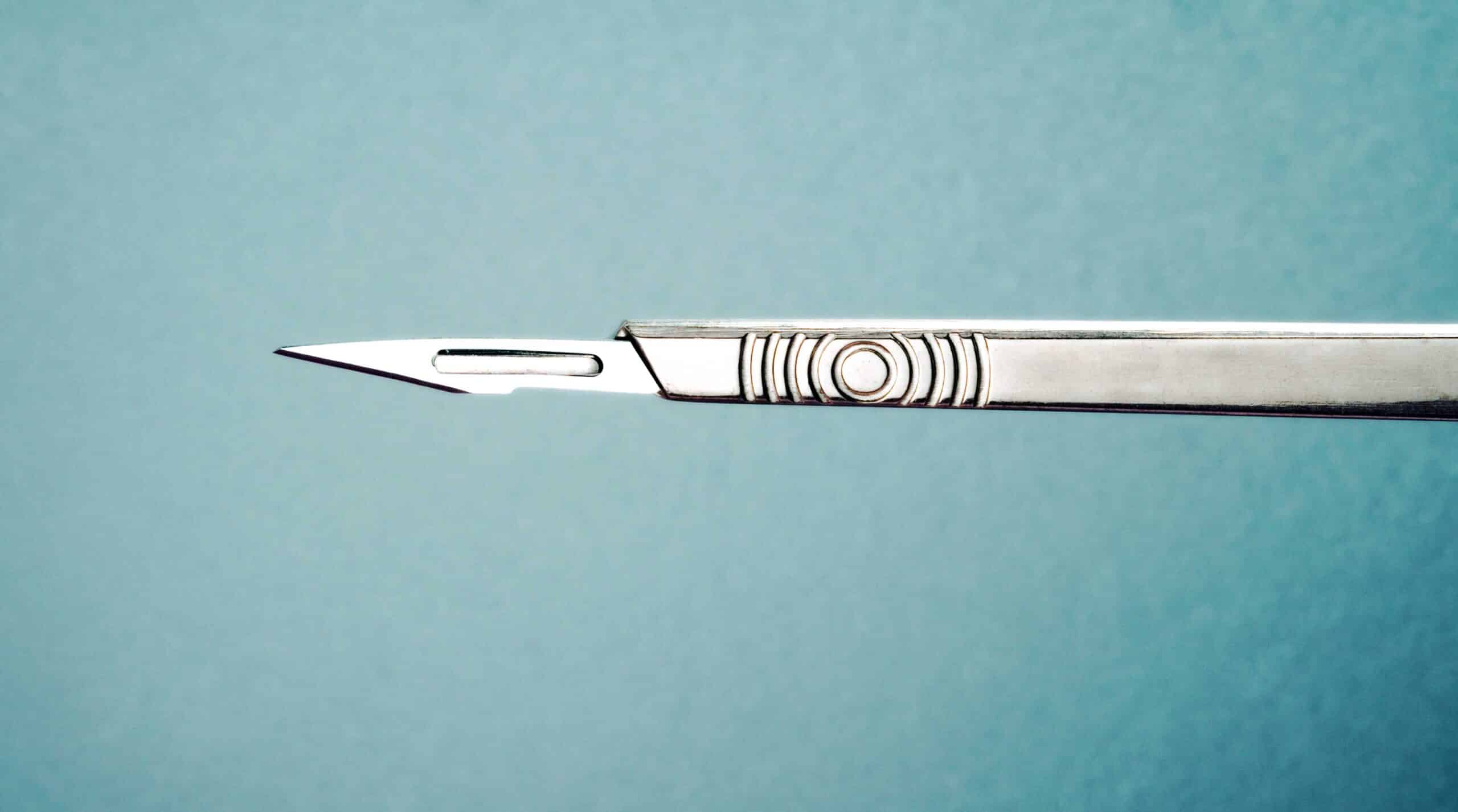

Brain stimulation can be used like a scalpel, rather than like a hammer, to cause a specific improvement in precise memory, a new study shows.

Precise memory, rather than general memory, is critical for knowing details such as the specific color, shape, and location of a building you are looking for, rather than simply knowing the part of town it’s in. This type of memory is crucial for normal functioning, and it is often lost in people with serious memory disorders.

“We show that it is possible to target the portion of the brain responsible for this type of memory and to improve it,” says Joel Voss, assistant professor of medical social sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and lead author of the study in Current Biology. “People with brain injuries have problems with precise memory as do individuals with dementia, and so our findings could be useful in developing new treatments for these conditions.”

By stimulating the brain network responsible for spatial memory with powerful electromagnets, scientists improved the precision of people’s memory for identifying locations. This benefit lasted a full 24 hours after receiving stimulation and corresponded to changes in brain activity.

Alzheimer’s didn’t cause memory loss for these 90-year-olds

“We improved people’s memory in a very specific and important way a full day after we stimulated their brains,” Voss says.

The research enhances scientific understanding of how memory can be improved using noninvasive stimulation. Most previous studies of noninvasive brain stimulation have found only very general and short-lived effects on thinking abilities, rather than highly specific and long-lasting effects on an ability such as precise memory.

The scientists used MRI to identify memory-related brain networks then stimulated them with noninvasive electromagnetic stimulation. Detailed memory tests were used to show that this improved spatial precision memory, and EEG was used to show that these memory improvements corresponded to indicators of improved brain network function.

The National Institutes of Health provided support.

Source: Northwestern University