In an important step toward a medical technology that could help restore independence of people with paralysis, researchers find the investigational BrainGate neural interface system has low rates of associated adverse events.

More than two decades ago, a team researchers set out with an ambitious goal to provide people with paralysis a revolutionary neurotechnology capable of turning thoughts about movement into actual action, using a tiny device that would one day be implanted in the surface of the brain.

Their work led to an ongoing effort to create the BrainGate brain-computer interface, designed to allow clinical trial participants with paralysis to control assistive devices like computers or robotic limbs just by thinking about the action they want to initiate.

Now, after decades of advancements, researchers are getting their best glimpse yet at the safety profile for this promising technology and what it means for long-term use by people affected by neurologic disease or paralysis.

The team’s new study analyzes more than 17 years of safety data on clinical trials testing the BrainGate technology. The study found a low rate of adverse events associated with the implanted brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and concluded that the technology should continue to be evaluated for its potential to help people with paralysis regain lost neurologic function.

“In the largest ongoing trial of intracortical brain-computer interfaces, the interim safety profile reported today supports the possibility that these systems may become restorative neurotechnologies for people with paralysis,” says Leigh R. Hochberg, an engineering and brain science professor at Brown University, a critical care neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and director of the BrainGate academic consortium leading the development and testing of the technology.

The new study is an important step for the BrainGate consortium and other BCI research as the current BrainGate clinical trial enters its 14th year.

“Intracortical brain-computer interfaces have so much promise for restoring communication and mobility,” says Hochberg, who also directs the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology in Providence, Rhode Island.

“Translating these advances in neural engineering to patient care will depend largely on whether the devices are accompanied by an acceptably low degree of risk.”

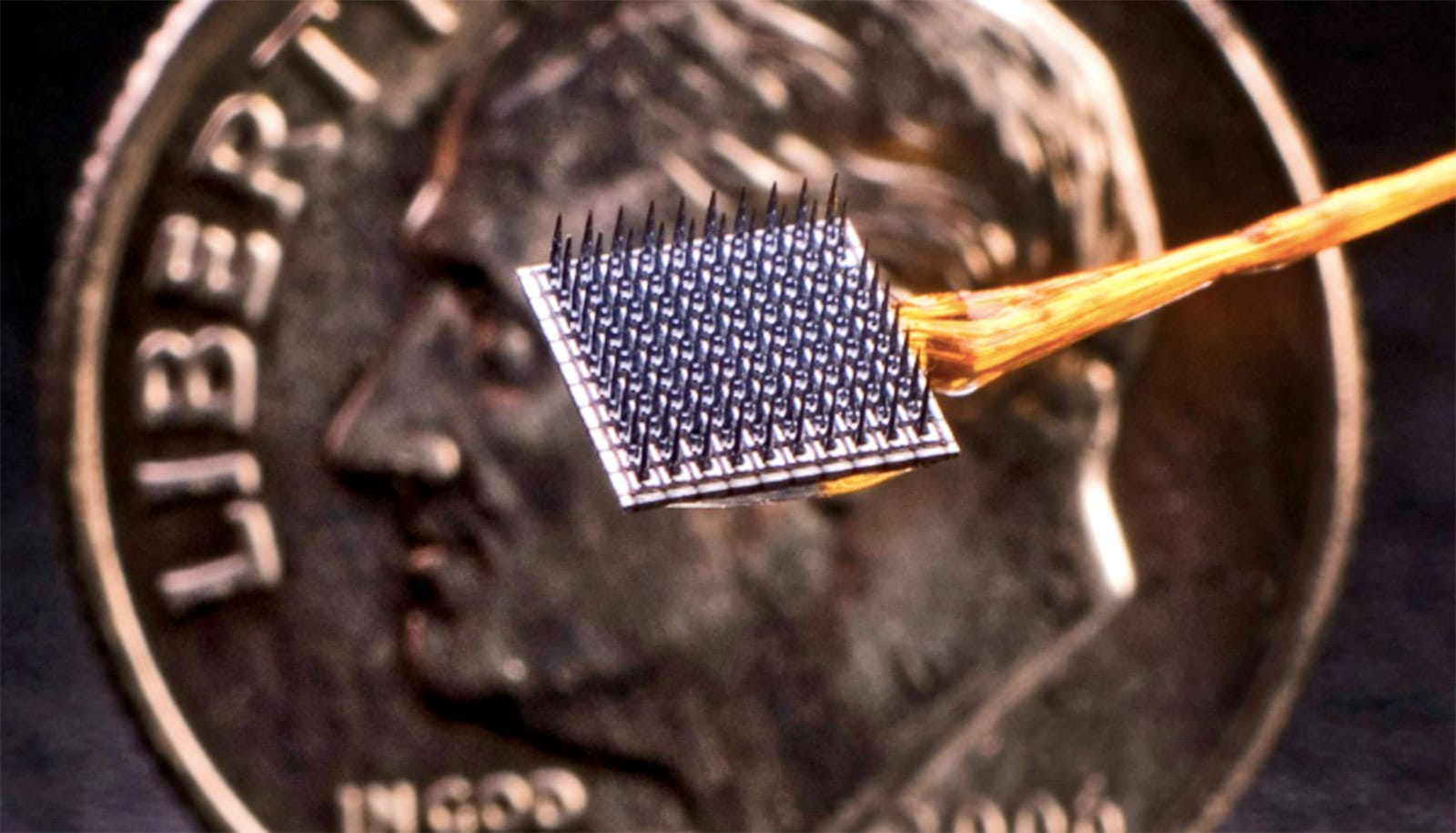

The BrainGate device is a type of BCI that is implanted in a part of the brain that controls limb movement. The microelectrode array—called a “Utah” array—is smaller than a contact lens and is placed into the surface of the motor cortex. It works by detecting neural signals associated with intended movements, sending them out to a small nearby computer that then uses algorithms to translate the signals into movement commands.

The ultimate goal of BrainGate is to restore communication, mobility, and independence for people with tetraplegia. Previous studies by BrainGate researchers have shown that the BCI can enable people to move robotic arms or even move their own paralyzed arm and hand.

The new BrainGate study evaluated a total of 12,203 days of safety data from 14 clinical trial participants with quadriparesis resulting from spinal cord injury, brainstem stroke, or ALS. Participants were ages 18 to 75 and were enrolled in BrainGate’s trials between 2004 to 2021. In that span, the study found, there were 68 device-related adverse events—the most common was skin irritation around the small portion of the device on top of a user’s head that connects the neural sensor array implanted in the brain to the nearby neural decoding system.

There were six serious adverse events determined to be related to the BrainGate device or surgical procedure. Two participants, both of whom had a history of traumatic brain injury, had brief post-operative seizures, which were easily treated. The researchers say none of the adverse events documented in the study were unanticipated, resulted in permanently increased disability, required removal of the device, or led to infections in the nervous system.

Data from the clinical trials came from seven sites across the US, including Mass General and the Providence VA Researchers at Mass General led the study in collaboration with colleagues from Brown, the VA, Stanford University, and several other institutions in the BrainGate consortium. The scientists write in the study that while the safety profile is a big step forward, there is still much work to be done to reach their ultimate goals for the technology.

“Overall, we are reassured by our findings over the past 17 years that the investigational BrainGate Neural Interface system is being deployed safely,” the researchers write. “Both our group and others continue to work on components and systems that would permit [BCIs] to become fully implanted, available to users around-the-clock, and incorporating a suite of design characteristics previously proposed.”

“In the future, I hope that BrainGate becomes an option for everyone with paralysis,” says John Donoghue, a professor at Brown. “The golden day would be when somebody who is paralyzed gets a BrainGate-like system implanted, and they go play basketball.”

The new study appears in Neurology. The research received support from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown University, and several additional funders noted in the paper.

Source: Brown University