Bowhead whales have a surprisingly diverse, constantly shifting vocal playlist, a new study shows.

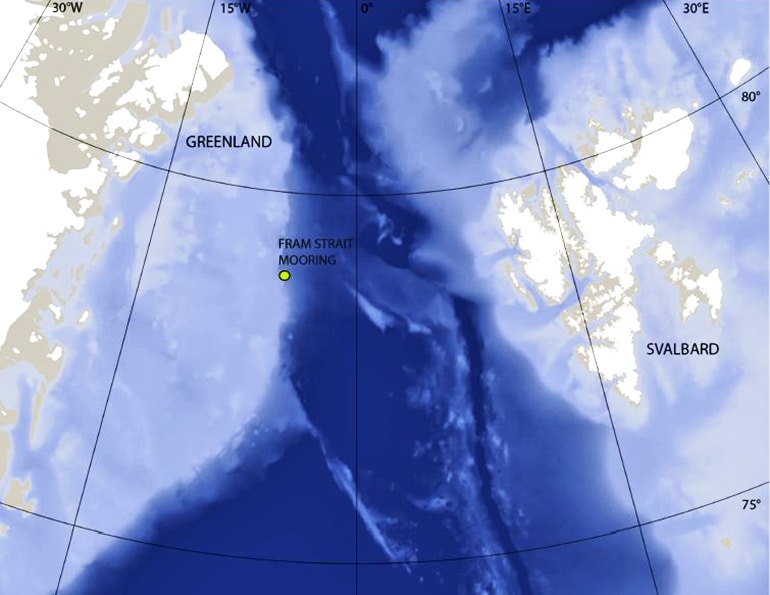

Scientists analyzed audio recordings gathered year-round east of Greenland. Humans almost hunted this population of bowhead whales to extinction in the 1600s and experts recently estimated their numbers at about 200 animals. Audio recordings gathered from 2010 to 2014 indicate a healthy population, and include 184 different songs.

“If humpback whale song is like classical music, bowheads are jazz,” says Kate Stafford, an oceanographer at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory and lead author of the paper that appears in Biology Letters.

“The sound is more freeform. And when we looked through four winters of acoustic data, not only were there never any song types repeated between years, but each season had a new set of songs.”

Singing 24 hours a day

Stafford has recorded whales’ sounds throughout the world’s oceans as a way to track and study marine mammals. She first detected bowhead whales singing off the other side of Greenland in 2007.

A previous study of the Spitsbergen whales off west Greenland reported in 2012 that the whales were singing continuously during the winter breeding season, the first hint that there may be a healthy population in that area.

“We were hoping when we put the hydrophone out that we might hear a few sounds,” Stafford said of the earlier study. “When we heard, it was astonishing: Bowhead whales were singing loudly, 24 hours a day, from November until April. And they were singing many, many different songs.”

The new paper extends that initial five-month dataset, and confirms that bowhead whales sing in this region regularly from late fall to early spring. In fact the hydrophones, which are underwater microphones, picked up slightly more singing in the later years of the study.

But what was most remarkable was the relentless variety in the animals’ songs, or distinct musical phrases.

Versatile virtuosos

The only other whale that sings elaborate songs—humpback whales—are widely studied in their breeding grounds off Hawaii and Mexico. The humpback’s melodious song is common to each population of males and shifts slightly during the winter breeding season. Each population debuts a new tune in the spring.

“It was thought that bowhead whales did the same thing, based on limited data from springtime,” Stafford says. “But those 2008 recordings were the first hint, and now this data confirms that bowhead whale songs are completely different from the humpbacks’.”

Animal songs are not the same as animal calls because songs are complex—distinct musical phrases that must be learned. Many birds and mammals use songs to identify themselves as individuals or as members of a group, among other uses.

“For marine mammals, acoustics is how they do everything,” Stafford says. “Humans are mostly visual animals, but marine mammals live in a three-dimensional habitat where sound and acoustic information is how they navigate, how they find food, how they communicate.”

No new babies for North Atlantic right whales?

Singing whales, like birds, may be doing some combination of acoustic competition with other animals and attracting mates, Stafford says. But little is known about the bowhead whales’ singing: whether only males make these sounds, whether individuals can share songs, and, most importantly, why their tune changes all the time.

“Why are they changing their songs so much?” Stafford says. “In terms of behavioral ecology, it’s this great mystery.”

The new data suggest bowhead whales may be similar to cowbirds and meadowlarks, birds that learn a diverse, ever-changing repertoire of songs, maybe because novelty offers some advantage.

“Bowhead whales do this behavior in the winter, during 24-hour darkness of the polar winter, in 95 to 100 percent sea ice cover. So this is not something that’s easy to figure out,” Stafford says. “We would never have known about this without new acoustic monitoring technology.”

Current research placing radio tags on bowhead whales may someday explain why the whale has evolved to become such a versatile virtuoso.

“Bowheads are superlative animals: they can live 200 years, they’ve got the thickest blubber of any whale, the longest baleen, they can break through ice,” Stafford says.

“And you think: They’ve evolved to do all these amazing things. I don’t know why they do this remarkable singing, but there must be a reason.”

Online maps track where whales and dolphins go

Researchers from the Norwegian Polar Institute and the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum are coauthors. The Norwegian Polar Institute, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Fund, Svalbard Science Forum, the Fram Centre Incentive Fund, and the Norwegian Research Council funded the work.

Source: University of Washington