People with blood type A get more severely ill from a kind of E. coli most associated with “traveler’s diarrhea,” research shows. This type of E. coli also causes illness among children in underdeveloped areas of the world.

The bacteria release a protein that latches onto intestinal cells in people with blood type A, but not blood type O or B, according to the study. A vaccine targeting that protein could potentially protect people with type A blood against the deadliest effects of enterotoxigenic E. coli (Escherichia coli) infection.

“We think this protein is responsible for this blood-group difference in disease severity,” says senior author James Fleckenstein, an associate professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “A vaccine targeting this protein would potentially protect the individuals at highest risk for severe disease.”

Enterotoxigenic E. coli are responsible for millions of cases of diarrhea and hundreds of thousands of deaths every year, mainly of young children. It primarily infects people living in or visiting developing countries. Some people infected with the bacterium develop severe, cholera-like, watery diarrhea that can be lethal. Others experience unpleasant symptoms but recover easily, while some don’t get sick at all.

Enterotoxigenic E. coli are not the cause of the current romaine lettuce-related outbreak. That outbreak involves a different kind of E. coli known as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O157:H7.

Years ago, doctors noted that children naturally infected with enterotoxigenic E. coli in Bangladesh seemed to get sicker if they had blood type A, but the reason for this was never tested. Fleckenstein, instructor in medicine Matthew Kuhlmann, postdoctoral researcher Pardeep Kumar, and colleagues investigated whether blood type influences disease severity by looking at what happened to people of different blood types who drank a cup of water laced with E. coli.

“I don’t want anyone to think they’re safe because their blood group is not A.”

In controlled human infection clinical trials, researchers at Johns Hopkins University gave healthy volunteers a dose of an E. coli strain originally isolated from a person in Bangladesh with severe, cholera-like diarrhea. Then, they observed the volunteers for five days. Those who developed moderate to severe diarrhea were treated with antibiotics. The disease comes on quickly, so anyone who was still healthy at the end of five days was unlikely to get sick later. Nonetheless, any remaining healthy participants also received antibiotics to clear the bacteria before going home.

Kuhlmann and colleagues obtained data and blood samples from 106 people, each of whom participated in one of four such studies. They found that people with blood type A got sick sooner and more seriously than those of other blood types. More than eight out of 10 (81 percent) of blood group A people developed diarrhea that required treatment, as compared with about half of people with blood group B or O.

Blood groups are based on the sugars that decorate the surface of red blood cells and other cells. People with group A blood have sugars that are distinct from those present in either B or O blood groups. People with blood group AB carry both A- and B-type sugars on their cells.

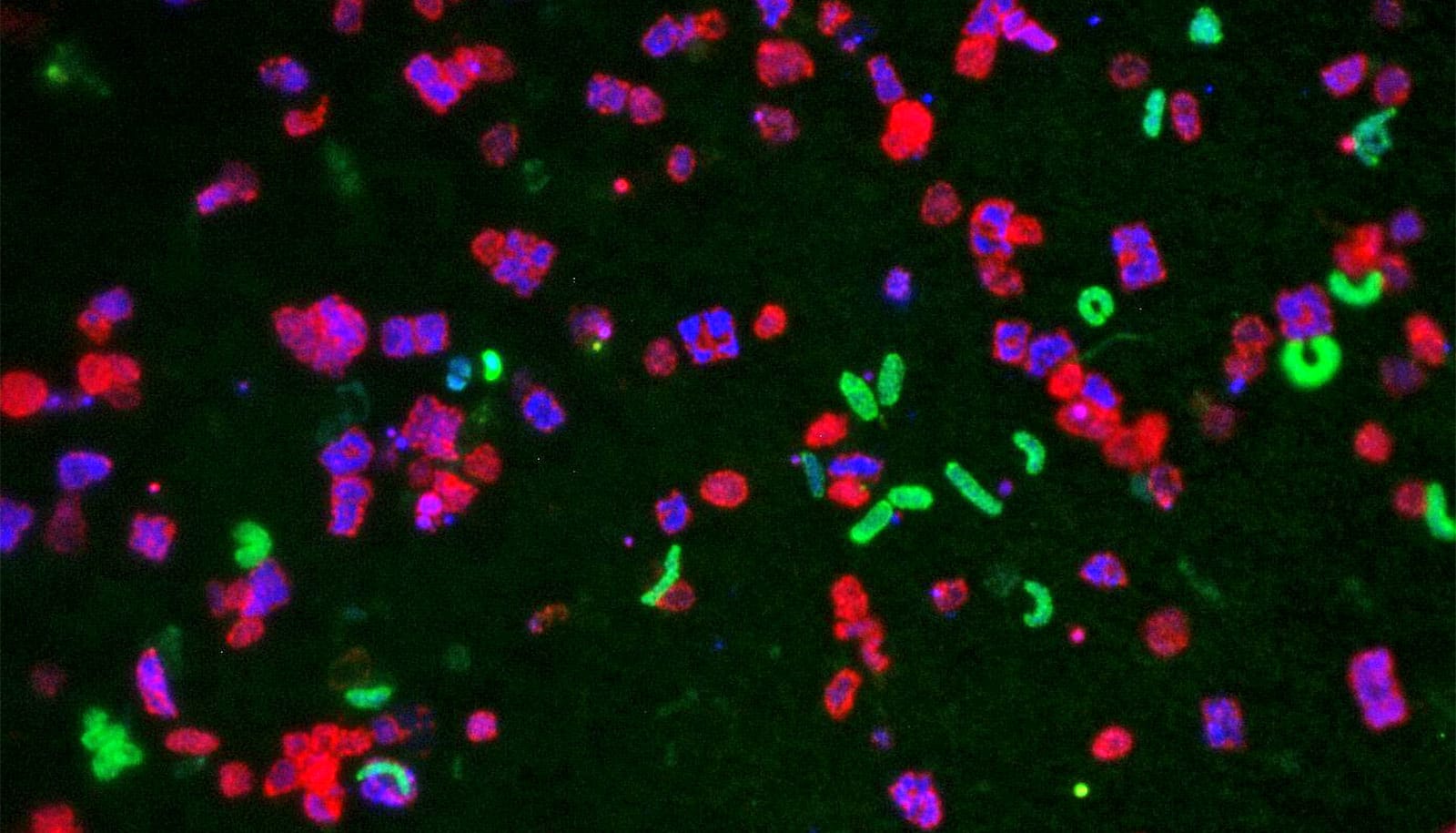

The researchers found that the bacteria produce a specific protein that sticks to A-type sugars–but not B- or O-type sugars–on intestinal cells. Since the protein also sticks to E. coli, it effectively fastens the bacteria to the intestinal wall, making it easy for them to deliver diarrhea-causing toxins to intestinal cells.

The effect of blood group in people infected with this strain of E. coli was striking and significant, but it doesn’t mean people should change their behavior based on blood type, the researchers say.

“I don’t want anyone to cancel their travel plans to Mexico because they have type A blood,” Kuhlmann says. “Or the converse: I don’t want anyone to think they’re safe because their blood group is not A. There are a lot of different species of bacteria and viruses that can cause diarrhea, so even though this blood-group association is strong, it doesn’t change your overall risk. You should continue taking the same precautions whatever your blood type.”

For small children and others who don’t have reliable access to basic sanitation or clean water, a vaccine could be lifesaving.

Basic hygiene—washing hands and purifying water—is the best protection against diarrheal diseases because it works against all kinds of organisms. But the people who suffer most from diarrhea are small children. For them, and others who don’t have reliable access to basic sanitation or clean water, a vaccine could be lifesaving.

There are many strains of enterotoxigenic E. coli, and developing a vaccine that protects against all of them has been a challenge because no single protein is found in all strains. To defend against as many strains as possible, scientists are studying dozens of proteins—but they still haven’t found a way to cover all strains. The protein identified in this study is found in many strains, so adding it to the mix could provide broader protection, especially for people at the highest risk for severe disease.

A virus ‘cocktail’ could one day treat food poisoning

The study appears in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. The work took place in collaboration with investigators at Johns Hopkins University, the National Institutes of Health, and the Naval Medical Research Center.

The National Institutes of Health; the Enteric Vaccine Initiative of PATH; the Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center at Washington University School of Medicine via the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the work.

Fleckenstein is listed as the inventor on a US patent 12/079,304 involving the EtpA adhesin.