Interactive software that “reads” and analyzes footprints left by black rhinoceroses can monitor the endangered animals’ movements and offers a way to protect them from poachers, according to a new study.

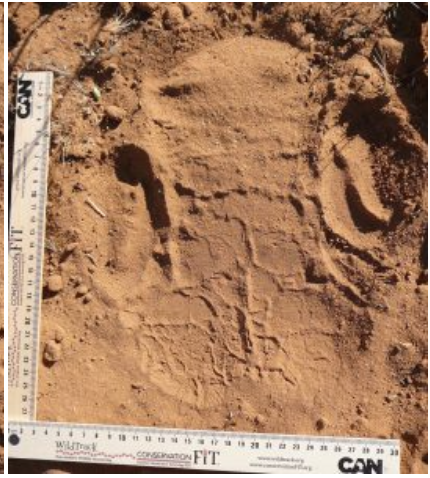

The software, called the Footprint Identification Technique (FIT), uses advanced algorithms to analyze more than 100 measurements of a rhino’s footprint.

Because each rhino’s footprint is as distinctive as a human fingerprint, the analyzed images can be archived electronically in a global database of previously collected footprint images for matching.

“If you find a match, you can identify the individual animal who left the mark and, by plotting the locations of all the other places that mark has been seen, track its movements without disturbing it or coming into close enough contact with it for there to be a risk of animal-to-human viral transmissions,” says Zoe Jewell, an adjunct associate professor at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment and principal research associate at the JMP Division of SAS who co-led the study and is co-creator of FIT.

“It’s a cost-effective approach that not only protects the health of the rhino and the human, but also brings a centuries-old tracking skill into the 21st century,” she says.

Jewell and colleagues are now working with Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism to train wildlife conservationists, land managers, local guides, and anti-poaching agents how to use FIT.

Namibia is home to an estimated 2,000 black rhinos, or about 90% of the species’ total population worldwide. While the government legally owns them, the animals are dispersed geographically on private lands across the country.

Stepped up government policing in recent years has significantly slowed the rate of loss due to poaching, but between 30 and 50 of the animals are still slain each year for their horns, which can sell for more than $60,000 a kilogram (2.2 lbs) on the Asian black market, where they are used in traditional medicine or displayed as a symbol of wealth and success.

“You essentially have these animals with horns worth $100,000 or more that disappear from sight into the Namibian back country, making them an almost irresistible target for poachers. Authorities often don’t know a rhino that’s gone missing has been poached until they find its bones or carcass,” says Jewell.

FIT allows scientists, managers, guides, or anti-poaching patrols to monitor the animals in three different ways, giving them flexibility to use it as best meets their individual needs and constraints, she says.

In the simplest option, the heel pattern on a digital image of the footprint is compared to images already in the FIT database to search for a match. This use is well-suited to situations where a random footprint is found in the wild.

The FIT software can also do a survey of footprints throughout the protected area and take measurements from each print to estimate the number of rhinos in that area. This can be useful information for calculating resource needs—the number of patrol vehicles, for instance—to monitor the animals effectively.

In the most advanced option, each individual rhino can be tracked and matched to its unique footprint using both FIT and heel-patterns. This creates an interactive library that anti-poaching patrols can use to search for animals at the highest risk, including those known to frequent areas under threat from poachers or those whose footprints haven’t been showing up in recent years.

“FIT is a distillation of the traditional ecological skills of the expert trackers who have lived and worked with in Africa for many years,” says Sky Alibhai, an adjunct associate professor at the Nicholas School and principal research associate at the JMP Division of SAS who co-led the study and co-developed the FIT technology with Jewell.

“Using FIT allows their skills to be used effectively in conservation. This can benefit whole communities.”

Jewell and Alibhai lead a nonprofit organization called WildTrack that promotes the use of FIT and other noninvasive, community-inclusive monitoring techniques worldwide, including artificial intelligence. The organization currently has more than 20 projects worldwide, including work to protect Bengal tigers in India, giant pandas in China, and mountain lions in the Americas.

The study describing the technology’s effectiveness for monitoring the endangered rhinos appears in PeerJ.

Additional coauthors are from the African Centre for Conservation Ecology at Nelson Mandela University; the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism; and the US Army Research Office.

Source: Duke University