Widespread use of biochar made from recycled waste in farming could both enhance crop growth and reduce health care costs by clearing the air of pollutants, new research suggests.

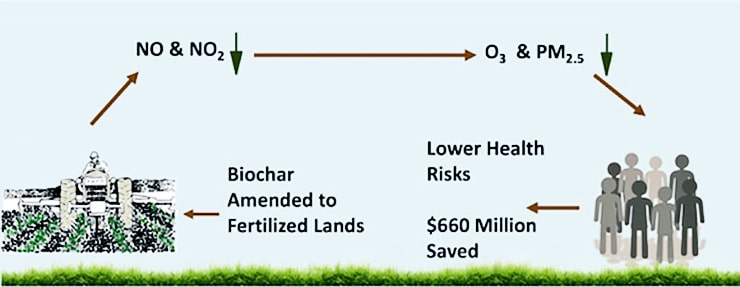

Biochar is ground charcoal produced from waste wood, manure, or leaves. Added to soil, the porous carbon has been shown to boost crop yields, lessen the need for fertilizer, and reduce pollutants by storing nitrogen that would otherwise be released to the atmosphere.

Urban dwellers in the American Midwest and Southwest, particularly those who live close to farmland, would gain the greatest benefits in air quality and health from greater use of biochar, the researchers say.

They say that, in the United States, Will, La Salle, and Livingston counties in Illinois; San Joaquin, San Diego, Fresno, and Riverside counties in California; Weld County in Colorado; Maricopa County in Arizona; and Fort Bend County in Texas would stand to save the most in health care costs from reduced smog.

“Our model projections show health care cost savings could be on the order of millions of dollars per year for some urban counties next to farmland,” says Ghasideh Pourhashem, a postdoctoral fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “These results are now ready to be tested by measuring changes in air pollutants from specific agricultural regions.”

“Our work shows that modest changes to farming practices can benefit the air and soil too.”

Pourhashem notes the key measurements needed are the rate of soil emission of nitric oxide (NO), which is a smog precursor, after biochar is applied to fields. Many studies have already shown that biochar reduces the emissions of a related compound, nitrous oxide, but few have measured NO.

“We know that biochar impacts the soil nitrogen cycle, and that’s how it reduces nitrous oxide,” says Caroline Masiello, a professor of earth, environmental, and planetary science. “It likely reduces NO in the same way. We think the local impact of biochar-driven NO reductions could be very important.”

NO contributes to urban smog and acid rain. NO also comes from cars and power plants, but the study focused on its emission from fertilized soils.

Iron-rich biochar filters arsenic from water

The team used data from three studies of NO emissions from soil in Indonesia, Zambia, Europe, and China. The data revealed a wide range of NO emission curtailment—from 0 percent to 67 percent—depending on soil type, meteorological conditions, and the chemical properties of biochar used.

Using the higher figure in their calculations, they determined that a 67 percent reduction in NO emissions in the United States could reduce annual health impacts of agricultural air pollution by up to $660 million. Savings through the reduction of airborne particulate matter—to which NO contributes—could be 10 times larger than those from ozone reduction, they wrote.

“Agriculture rarely gets considered for air pollution control strategies,” says Daniel Cohan, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering. “Our work shows that modest changes to farming practices can benefit the air and soil too.”

Biochar changes how water flows through soil

The study appears in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

The NASA Air Quality Applied Sciences Team, Rice’s Shell Center for Sustainability and the Baker Institute supported the research.

Source: Rice University