Freshly burned longleaf pine forests have more than double the total number of bees and bee species than similar forests that have not burned in over 50 years, new research shows.

For many forests, fire is as essential as rainfall. But while several studies have outlined the benefits of human-controlled prescribed burns on forest ecosystems, scientists understood little about how prescribed burns, or fires in general, may affect pollinators.

“There is global concern about the decline of insects in general, and pollinators in particular, so it’s really important for land managers to understand how prescribed fire affects insect communities,” says study coauthor Elsa Youngsteadt, an assistant professor in the applied ecology department at North Carolina State University.

“Given the importance of fire in maintaining longleaf pine ecosystems overall, you would expect it to be good for the region’s native bees. But it’s also easy to imagine small bees and their nests, especially nests in twigs and stems, just getting incinerated. We weren’t sure where we would find the most robust pollinator community.”

Controlled burns

For the study in Environmental Entomology, researchers worked with the Walthour-Moss Foundation’s longleaf pine savannah reserve, established to protect this endangered pine.

The reserve regularly burns 90% of its plots in 3-year cycles. Humans haven’t burned the remaining 10% of plots for at least 50 years. This provided an ideal opportunity to compare bee abundance and diversity between unmanaged and managed ecosystems.

“The southeastern US has some of the highest lightning strike rates in the world, which used to contribute to low-intensity fires passing through the longleaf pine savannas every 2 or 3 years,” Youngsteadt says. “But agriculture, development, and logging fragmented this landscape and blocked the movement of fire.”

Researchers placed bee “traps” at 16 sites: four burned the year of sampling, four burned one year before sampling, four burned two years before sampling, and four unburned control sites.

They found that burned sites supported 2.3 times more total pollinators than plots that had not burned in 50 years. Burned sites also had 2.1 times as many different bee species as unburned sites. Within those burned areas, bee abundance and diversity tended to be greatest at sites most recently burned, and this abundance and diversity decreased with time since the last fire.

Why so many bees?

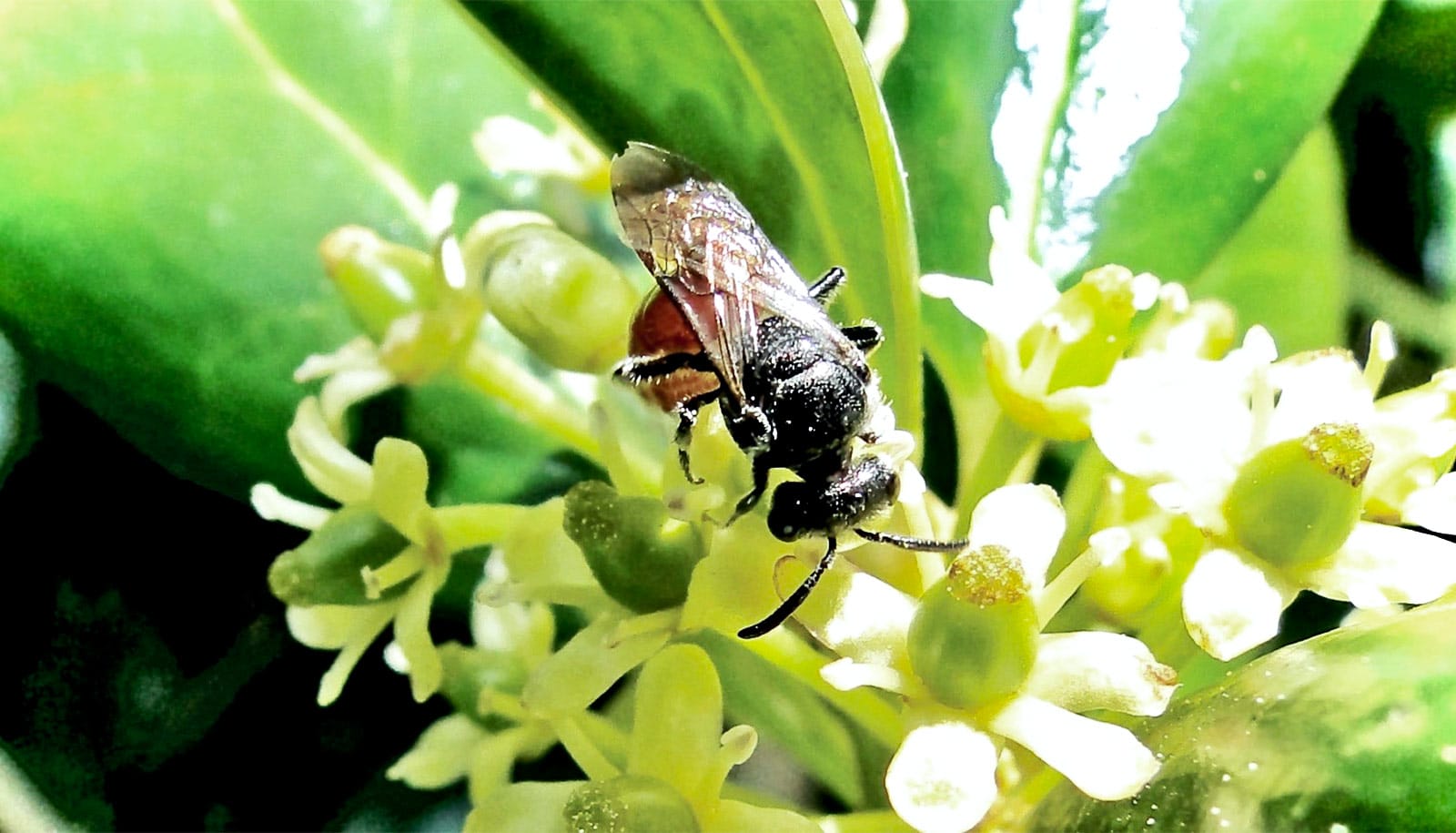

Fires maintain openings in the forest canopy, reduce ground cover, and release nutrients into soils at the same time, creating the perfect environment for large blooms, increasing the flower resources pollinators rely on.

The researchers also found that the low-intensity prescribed burns did not reduce the amount of nesting material for above-ground nesting pollinators, and fires did not affect the abundance of above-ground nesting pollinators. Meanwhile, below-ground nesting species appeared to benefit from the increased access to bare soil.

“It’s great news that prescribed fire, as currently used in longleaf pine savannas, is helping to support the pollinator community,” Youngsteadt says. “But there’s still a lot to learn.

“For example, the fires in this study were set in the winter, but many land managers use summer burns. Knowing the effects of fire in different seasons will be an important next step, as will knowing the optimal area of land to burn at any one time.”

The Walthour-Moss Foundation funded the work.

Source: NC State