“Survival of the friendliest” outweighs “survival of the fittest” for groups of bacteria, according to new research.

The research reveals that bacteria would rather unite against external threats, such as antibiotics, rather than fight against each other. The discovery is a major step towards understanding complex bacteria interactions and the development of new treatment models for a wide range of human diseases and new green technologies.

For a number of years the researchers have studied how combinations of bacteria behave together when in a confined area. After investigating many thousands of combinations it has become clear that bacteria cooperate to survive and that these results contradict what Darwin said in his theories of evolution.

“In the classic Darwinian mindset, competition is the name of the game. The best suited survive and outcompete those less well suited. However, when it comes to microorganisms like bacteria, our findings reveal the most cooperative ones survive,” explains Søren Johannes Sørensen, a professor of microbiology at the University of Copenhagen.

Bacteria survival as team sport

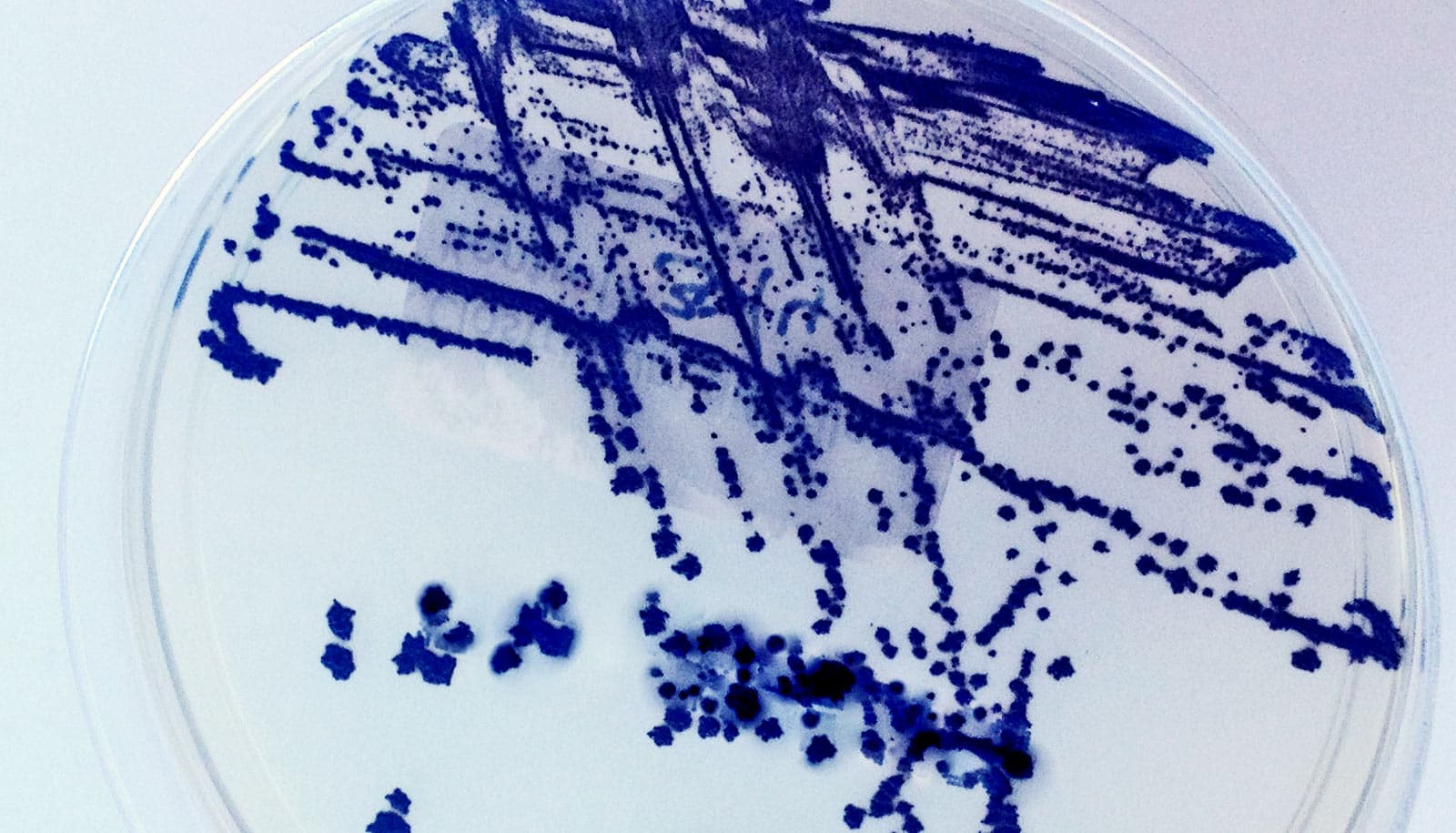

By isolating bacteria from a small corn husk (where they were forced to “fight” for space) the scientists were able to investigate the degree to which bacteria compete or cooperate to survive. They selected the bacterial strains based on their ability to grow together. Researchers measured bacterial biofilm, a slimy protective layer that shields bacteria against external threats such as antibiotics or predators. When bacteria are healthy, they produce more biofilm and become stronger and more resilient.

Time after time, the researchers observed the same result: Instead of the strongest outcompeting the others in biofilm production, bacteria allowed space for the weakest, so they could grow better than they would have on their own. At the same time, the researchers could see that the bacteria split up laborious tasks by shutting down unnecessary mechanisms and sharing them with their neighbors.

“It may well be that Henry Ford thought that he had found something brilliant when he introduced the assembly line and worker specialization, but bacteria have been taking advantage of this strategy for a billion years,” says Sørensen, referring to the oldest known bacterial fossils with biofilm.

“Our new study demonstrates that bacteria organize themselves in a structured way, distribute work, and even help each other. This means that we can find out which bacteria cooperate, and possibly, which ones depend on each another, by looking at who sits next to who,” he says.

All alone vs. part of the team

The researchers also investigated what properties bacteria had when they were alone versus when they were with other bacteria. Humans often discuss the workplace or group synergy, and how people inspire each other. Bacteria take this one step further when they survive in small communities.

“Bacteria take our understanding of group synergy and inspiration to a completely different level. They induce attributes in their neighbors that would otherwise remain dormant. In this way groups of bacteria can express properties that aren’t possible when they are alone. When they are together totally new features can suddenly emerge,” Sørensen explains.

Understanding how bacteria interact in groups has the potential to create a whole new area in biotechnology that traditionally strives to exploit single, isolated strains, one at a time.

“Bio-based society is currently touted as a solution to model many of the challenges that our societies face. However, the vast majority of today’s biotech is based on single organisms. This is in stark contrast to what happens in nature, where all processes are managed by cooperative consortia of organisms. We must learn from nature and introduce solutions to tap the huge potential of biotechnology in the future,” says Sørensen.

The research appears in the ISME Journal.

Source: University of Copenhagen