We may finally know how bacterial cells trigger their defense against outside attacks, according to new research.

The study also describes how researchers can activate the defense systems on cue. This discovery could be an important cornerstone in fighting diseases in the future.

The researchers have shown how a cell under attack from a virus activates a molecule called COA (cyclic oligoadenylate), which in turn activates a so-called protein complex called CSX1 to eradicate the attacker.

“Expressed in popular terms, the CSX1 starts cutting up the intruder. We can see how CSX1 is activated, rotates, and starts defending the cell, once COA is activated,” says Guillermo Montoya from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research at the Faculty of Health and Medical Science at the University of Copenhagen.

Turning on the defenses

The researchers have also managed to successfully activate the process themselves. They sent a COA molecule after the protein complex and thus started the defense mechanism.

“In short, we have found a switch that turns on the cell’s defense system when we want it to, and so we can diffuse possible attacks,” Montoya says.

It is the first time ever that researchers have managed to map and activate a bacterial “immune system.”

“A few years ago, science wasn’t even aware that bacteria had some sort of immune defense system. With this discovery, we have come a great deal further in terms of understanding these mechanisms,” Montoya says.

Furthermore, the discovery is interesting because the defense system in bacteria resemble in many ways the human innate immune system.

“Therefore, it is also a step along the way of understanding the human immune system better as well as knowing how to fight bacteria and defend oneself against viruses and in the long run even multiple resistance,” Montoya says.

A closer look at bacteria

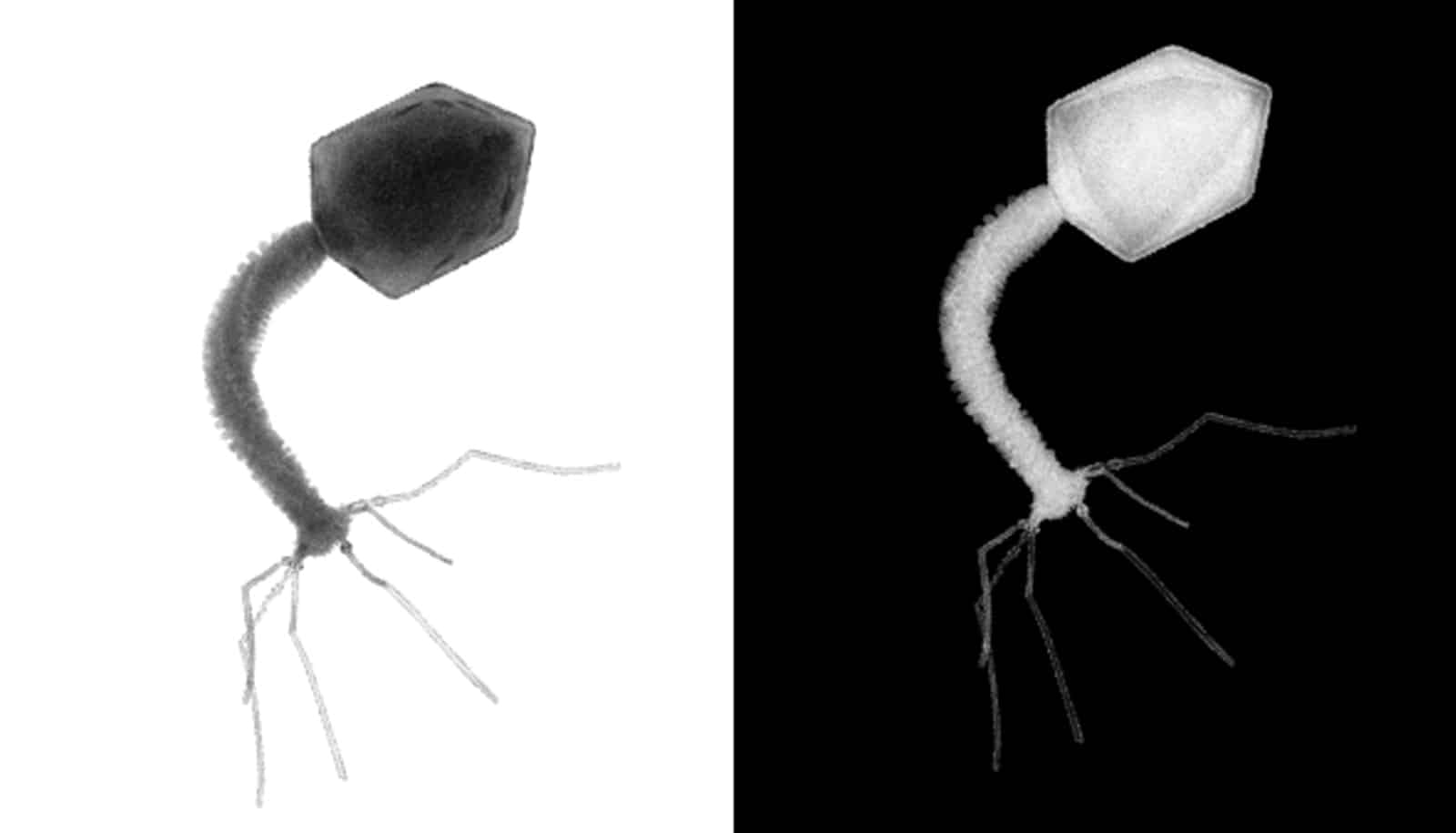

To discover the bacteria defense system, researchers used an x-ray crystallography at an establishment in Switzerland and one of the world’s most powerful microscopes—the synchrotron MAX IV—in Lund, Sweden.

The image of the CSX1protein complex was made possible by the advanced cryogenic electron microscope at the University of Copenhagen’s high tech CryoEM facility—in popular terms a strong magnifying glass.

“CSX1 is approximately 0.00005 mm long. This equates cutting one millimeter into 10,000 slices and then placing five pieces on top of each other. We have taken the pictures one by one and made a short film that reveals the activity inside CSX1,” Montoya explains.

The research appears in Nature Communications.

Support for the work came from the Novo Nordisk Fonden. Researchers from the Novo Nordisk Center for Protein Research at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciencem and the Danish Archea Center at the Faculty of Science, and Lund University contributed to the work.

Source: University of Copenhagen