New research digs into how augmented reality affects people’s behavior—in both the physical world and a digitally enhanced one.

Researchers found that after people had an experience in augmented reality (AR)—which goggles that layer computer-generated content onto real-world environments simulated—their interactions in their physical world changed as well, even when they weren’t wearing the AR device. For example, people avoided sitting on a chair they had just seen a virtual person sit on.

Researchers also found that the presence of a virtual person appeared to influence participants in a similar way a real person next to them might.

“We’ve discovered that using augmented reality technology can change where you walk, how you turn your head, how well you do on tasks, and how you connect socially with other physical people in the room,” says study leader Jeremy Bailenson, a professor of communication at Stanford University.

Their findings mirror much of the research Bailenson has done on virtual reality (VR). While VR attempts to simulate a real-life environment and take the user out of the present setting, AR technology layers digital information atop the user’s physical surroundings.

In recent years, many technology companies have focused on developing augmented reality goggles and other products, shifting away from their previous emphasis on virtual reality, Bailenson says.

Bailenson says today’s AR goggles can project a realistic, 3D version of an actual person in real time onto the physical surroundings of the goggles-wearer. This allows for groups of people across the world to make eye contact and communicate nonverbally in other nuanced ways—something that video conferencing struggles to achieve.

“AR could help the climate change crisis by allowing realistic virtual meetings, which would avoid the need for gas to commute or flying to meetings in person,” Bailenson says. “And this research can help bring attention to the possible social consequences of AR use at a large scale, so the technology can be designed to avoid these issues before becoming ubiquitous.”

Hanging out with ‘Chris’

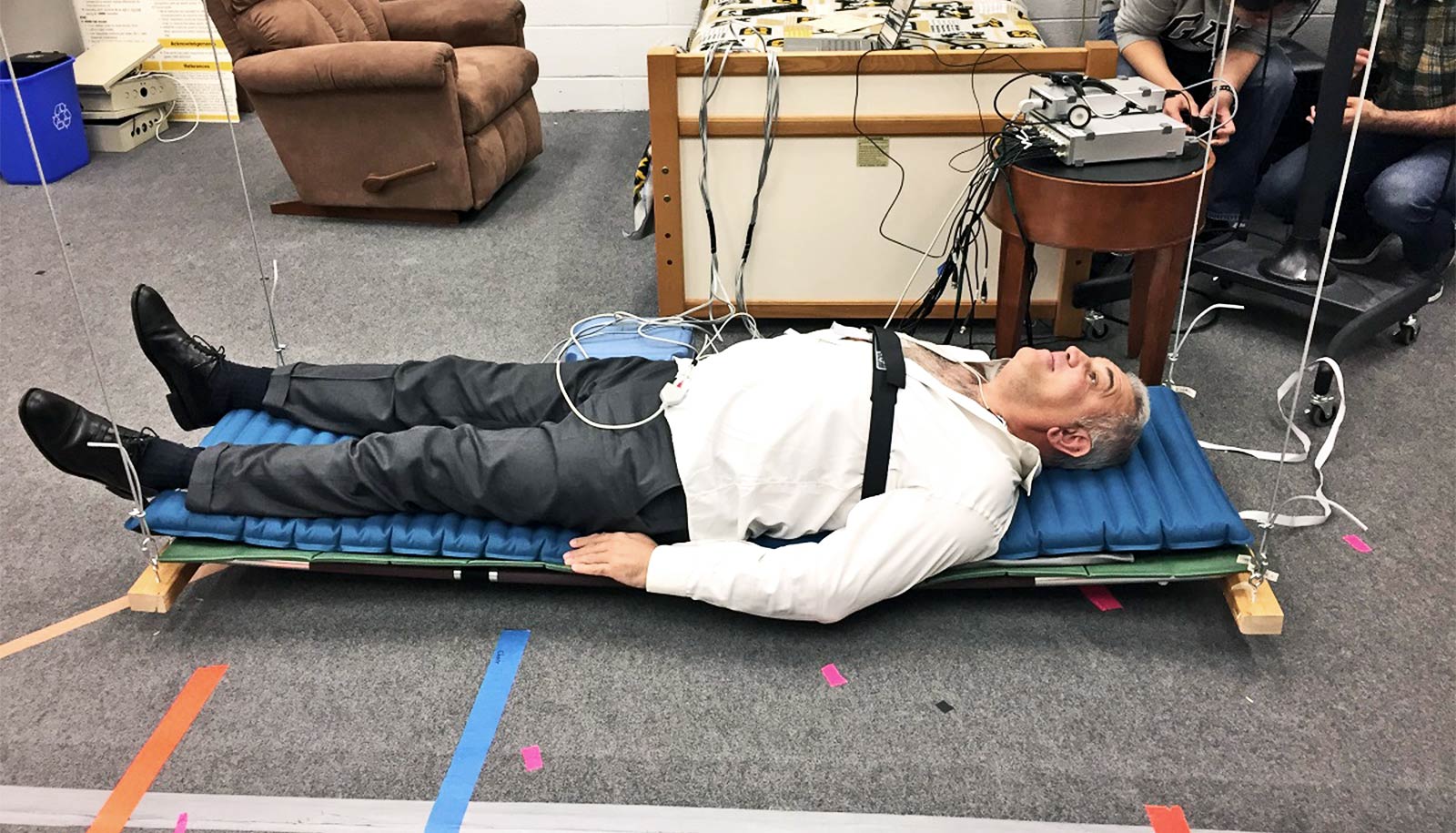

To examine how AR affected the way people behaved in social situations, researchers recruited 218 participants and conducted three studies. In the first two experiments, each participant interacted with a virtual avatar named Chris who would sit on a real chair in front of them.

The first study replicated a traditional psychology finding known as social inhibition. Just as people complete easy tasks with ease and struggle with more challenging ones when they have a person watching them in the real world, the same held true when an avatar was watching study participants in augmented reality, the researchers found.

Study participants completed easy anagrams faster but performed poorly on the complex ones when they could see avatar Chris in their AR field of vision.

Another study tested whether participants would follow accepted social cues when interacting with avatar Chris. Researchers measured this by tracking whether participants would sit on the chair that avatar Chris previously sat on.

Researchers found that all participants who wore the AR headset sat on the empty chair next to Chris instead of sitting right on the avatar. Of those participants who researchers asked to take off the headset before choosing their seat, 72 percent still chose to sit in the empty chair next to where Chris sat previously.

The lingering AR world

“The fact that not a single one of the subjects with headsets took the seat where the avatar sat was a bit of a surprise,” Bailenson says. “These results highlight how AR content integrates with your physical space, affecting the way you interact with it. The presence of AR content also appears to linger after the goggles are taken off.”

In the third study, researchers examined how AR affects the social connection between two people who are having a conversation while one of them wears an AR headset. Researchers found that those wearing AR goggles reported feeling less socially connected to their conversation partner.

Bailenson says that additional studies, which he and his team are now working on, are necessary to further examine the effects of augmented reality.

“This paper scratches the surface of the social-psychological costs and benefits of AR use, but much research is needed to understand the effects of this technology as it scales,” the researchers write.

These findings appear in PLOS ONE. Support for the research came from the National Science Foundation.

Source: Stanford University