A new artificial “nose” can sniff out damaged fruit and spoiled meat.

Although smell has historically played an important role in the fight against diseases such as the plague and tuberculosis, the human nose is generally not sensitive enough to be used as a reliable diagnostic tool.

However, the new artificial “nose” inspired by our sense of smell could now make it possible to detect undiagnosed disease, hazardous gases, and food that is starting to spoil.

And it is all made possible with technology that already exists: Antennas.

“We are literally surrounded by technology that communicates using antenna technology,” says Michael Cheffena.

Cheffena is a professor of telecommunications at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Gjøvik and believes that this technology can be used for far more than just communication.

“By giving the antennas sensor functions, the existing infrastructure can be used in new areas of application. This has been one of the main motivations for investigating whether antennas can be used for these purposes,” he adds.

Cheffena explains that previous attempts to create so-called “electronic noses” have not had the advantage of having an existing infrastructure readily available. They have also been affected by a number of other challenges that antenna technology can potentially resolve.

“Other electronic noses can have several hundred sensors, often each coated with different materials. This makes them both very power-intensive to operate and expensive to manufacture. They also entail high material consumption. In contrast, the antenna sensor consists of only one antenna with one type of coating,” says Cheffena.

That must surely come at the expense of accuracy and functionality?

“On the contrary,” says Yu Dang, a PhD research fellow at the manufacturing and civil engineering department at NTNU in Gjøvik and the lead author of a recently published research article on the new “antenna nose” in the journal Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical.

According to Yu Dang, their sensor distinguishes between the various gases it has been tested on with an accuracy of 96.7%. This is a result that is not only on par with the performance of the best electronic noses to date, but in some areas, it even surpasses them.

The antenna transmits radio signals at a range of different frequencies into the surroundings. It then analyzes how they are reflected back. The way the signals behave changes based on the gases present, and because the antenna transmits signals at multiple frequencies, the changes create unique patterns that can be linked to specific volatile organic compounds.

Volatile organic compounds are gases that are commonly found in the air. They are characterized by a low boiling point, meaning they tend to evaporate at low temperatures. And even though they can neither be seen nor felt, you will definitely have smelled several of them.

All living organisms, including plants, emit volatile organic compounds, often as a means of protecting themselves from pests or communicating with one another. The smell of freshly cut grass is a well-known example of this.

The petrol fumes from your lawnmower are another example. Since many of the products we use and the materials we surround ourselves with also emit volatile organic compounds, a large number of gases in various combinations will be present in most environments. This makes the task of distinguishing significant gases from insignificant ones extremely challenging.

Dang explains that it becomes even more difficult when isomers are also added to the mix.

“Isomers are chemical compounds that have the same molecular formula, but where the atoms are bound together in slightly different ways,” he says.

According to the researchers they are a bit like twins: very similar, yet not identical.

“These compounds have long been a challenge for this type of sensor technology. Even the most sophisticated E-noses consisting of many different sensors struggle with them,” Dang says.

He is therefore very pleased that their antenna sensor performs so well even on these difficult compounds.

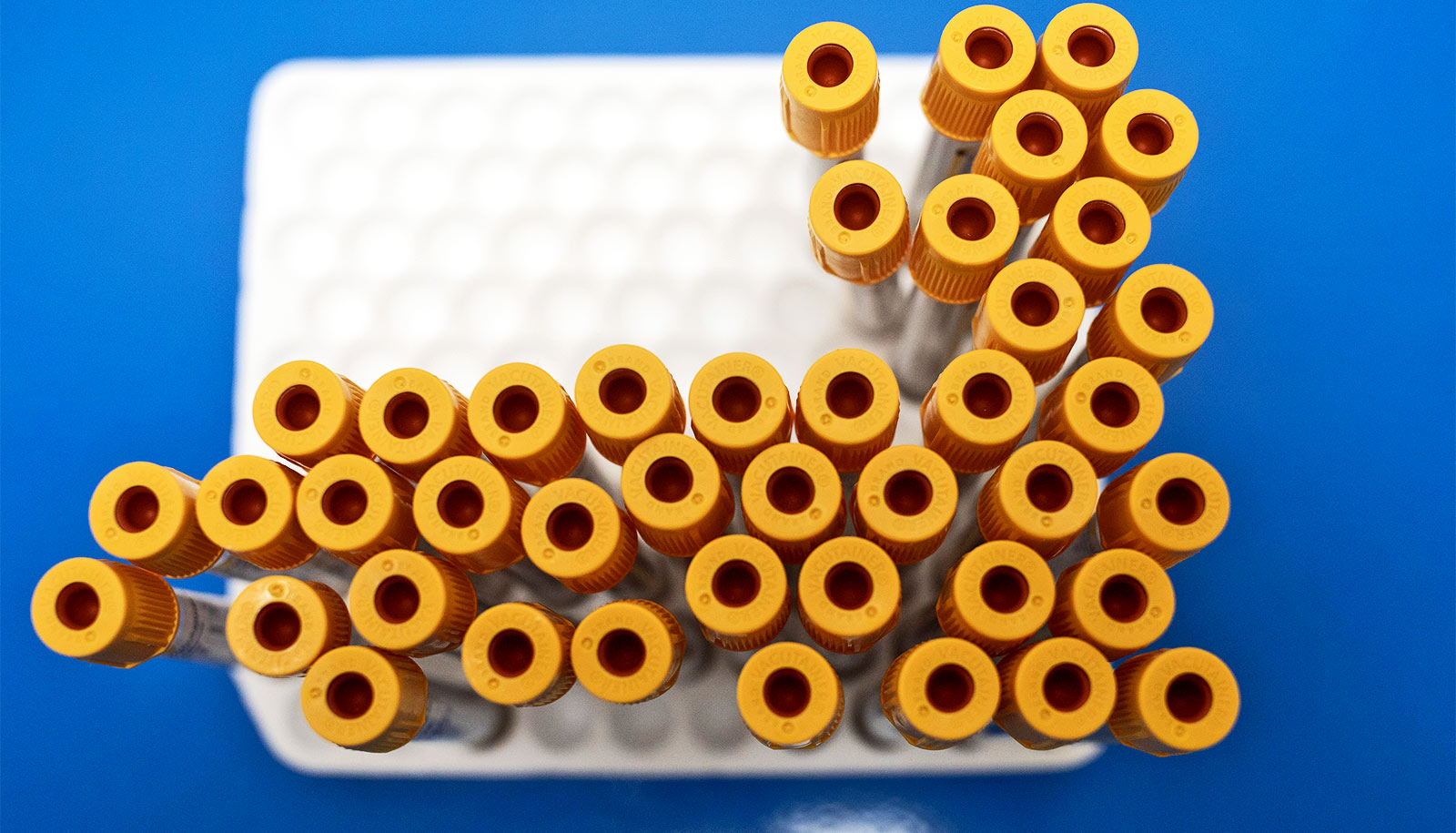

So far, the sensor technology has been tested on impact-damaged fruits and meats of varying ages. By adjusting the algorithms that detect the unique “fingerprints” of the different gases, the researchers believe the technology may also be able to smell diseases.

“Volatile organic compounds enable trained dogs to detect health-threatening changes in blood sugar and diseases like cancer, so the principle is largely the same,” Dang says.

Unlike dogs, however, the antenna sensor does not require months of training or specialized handlers to be used. The basic technology is something you already have in your living room.